Start with a talk. Draw a picture. Grow.

Step into writing like entering a swimming hole. Cold at first, but warm when immersed. Doable. A post of indirections and a request for help.

Read time: about 8 minutes. This week: an idiosyncratic reflection on writing, using pregnant procrastinations of discovery, note-booking, sense-rich thinking (maybe 4 minutes). And an interruption of 1960s pop art that I’m researching — maybe you can help (another 4 minutes). Next week: Art, creativity, and technology — what a jumble!

Feel free to share this post. It might make someone feel better, or maybe you know someone who knows Swiss pop art of the 1960s.

Like most writers, I try to plan myself out of worries. I have deadlines. I have what I call my “editorial plan” (actually, just a list of almost clear topics). I have blank paper and abundant ink.

And I have my messy desk for distraction and rich procrastination. “Anyone can do any amount of work,” Robert Benchley wrote in a Chicago Tribune column published in February 1930, though he added a significant qualification — “Anyone can do any amount of work, provided it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.”

I feel seen.

But I also have the feeling that what may look like procrastination is actually preparation. I seem to have gradually slid into a method of writing and teaching students to write that uses some indirection — a form of diversion and distraction. It seems to help students move toward their research papers.

To learn, have an audience

How do you get written things done? How do you create an argument, hold forth a perspective, present your findings — activities that are quite complex and, for many first-year undergraduates, rather daunting? Often steeped in a teacherly tradition of the “five-paragraph essay,” many college-aged writers are in some sense over-planned, simply because they have a handy and supposedly general-use framework for written work. It’s been drilled into their experience of essays. The trouble? It doesn’t work, actually. It’s either too wooden to breathe life into prose, or often it’s too cramped to deliver a message, even inelegantly.

Rather than approaching writing as a mode of discovery and learning, the five-paragraph essay serves as a form to be filled out, a questionnaire with slots. Except … we don’t converse in just five paragraphs. We hear abundantly. We respond, sometimes with vigor. We develop our ideas … incrementally.

A conversation — even a fairly contrived form of conversation — helps get people off the block. Everyone can hold forth on a topic for a few minutes and most can even be interesting or even insightful in the process. A brief class presentation works, and it has the advantage of allowing students to attach their ideas to visual representation, to oral and aural experience, and within a social context. In a real sense, the products that students conjure up in their presentation is far more “immersive” and engaging for them than they often realize as they bring it together.

The presentation is a lesson in audience, even as it reinforces students’ learning of “the topic.” Reinforces? No, actually something stronger than that, I think. More central. More core. They learn because they have an audience.

My students’ class presentations are ten minutes long, followed by a supportive, five-minute Q&A, which is in turn sounded out in the cafeteria and dorm for further response. The little presentations can switch on a topic in our minds.

But most importantly, students get something that they can really procrastinate with. A “slender idea” shared.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

“Slender ideas” and imagery grow into prose

Jillian Hess looked at Patricia Highsmith’s cahiers — spiral bound college notebooks, all emblazoned with “COLUMBIA” on the covers. Highsmith called them cahiers, her rather exalted French term for her notebooks, thirty-eight of which have survived.

Hess drew an important bit of advice from Highsmith: “Write down all these slender ideas,” Highsmith wrote in Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction. “It is surprising how often one sentence, jotted in a notebook, leads immediately to a second sentence. A plot can develop as you write notes. Close the notebook and think about it for a few days — and then presto! you’re ready to write a short story.”

A great phrase: “Write down all these slender ideas,” and I think one that writing teachers might use well with students who too often think of writing tasks as monumental and forbidding. Highsmith’s words also trust time and mind. You capture the “slender ideas,” let them grow, set them aside, mature. If you’re like me (and I think many are), your procrastination — even counting the studied and nurturing indirections from a mentor — can let the fruit of slender ideas emerge.

Start modestly, I’d say to students and teachers. And think broadly and in new forms, too.

The class presentations, a species of “slender ideas” in my seminars, have advantages beyond circling an audience. They are aural, oral, visual, and even have a dance quality through gesture. People’s whole bodies get into their topics, and I am increasingly convinced that we distill our best thought and find our first prose when we unreservedly invest our senses. Hess includes some great images in her essay on Highsmith’s cahiers. They show the play that Highsmith used to adorn her spiral notebooks, and I can’t help but think her ornament helped fertilize her slender ideas.

“Writing comes from drawing, from reality that was tangible first and then became distant as an abstract sign. Ideas … may well have their source in mark-making, not the other way around.” Those words come from a table of contents page from the 2018 issue of Camera Austria International, perhaps an excerpt from an essay by Adam Szymczyk. The excerpt turns to photography, a capture of imagery, and claims that “[p]hotography is a form of writing too — not only in the etymology of the term. Photography is considered capable of an accurate rendition of reality at hand, and so is painting—both realist or abstract…. It is the movement of metaphors, the essential poetic operation of carrying things over, bringing them forth, moving things with words and images.”

Imagery, sound, movement, slender ideas on a page — all work together to frame new ideas and discovery.

I often think we need to slow ourselves down to do the best learning and creation. And help our students do the same.

And now for something completely different…

I wonder if you can help. I’m looking for someone. The lady with the headlights.

A section of my long-procrastinated, dabbled-at book project concerns glamour and the car. One of its chapters focuses in particular on the most glamorous of cars — the Jaguar E-type that came to embody the sex, glitz, and energy of the 1960s. There’s no shortage of its “glam” from magazines and advertising — and not just to spur sales of the cars. In short order during the 1960s, the Jaguar E-type transformed from a passively glamorous object into an object conferring glamour (among others things, like sex appeal or signatures of fame). The power has persisted to this day.

The car became an icon, in (close to) a conventional sense of the word.

As an icon, it also became somewhat its own nemesis, since its meanings also included social privilege, wealth, excess, sexual exploitation, consumer culture and the like. For some, the E-type (and some would say Jaguar’s whole line of cars) represents seductions, excesses, and abuses — much as the Mercedes-Benz three-point star had become for activists and protesters in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s important that my discussion of glamour includes those elements as well — seeing that they emerge from, and I think shadow and qualify, more “conventional” media and often commercial representations of the car.

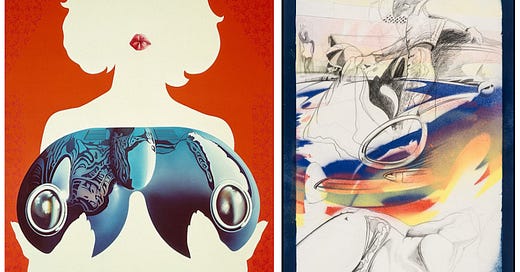

Some artworks use the E-type for cultural critique. Hugo Schuhmacher used the image of the car in some of his works, which mix “tachist” style with pop art as in Corrida — Spanish for “bull fight.” (See the image above.) Schuhmacher juxtaposed images of the car in sprayed acrylic, in part stenciled (note the wheel wells), with pencil drawings of women in swimsuits lounging or waving on a beach. A pencil-drawn bullfighter swirls his cape as if releasing the car, sending it forward. Only the car is rendered in color. The women have no faces, though their shapely torsos are easy to see. The Kunstmuseum Thun, which includes Corrida in its collection, notes this juxtaposition: “[T]he picture refers to Schuhmacher’s socially critical examination of sexist depictions and the world of consumerism and affluence, topics that he devoted himself to until the end of the 1970s.” For Schuhmacher, the Jaguar E-type signaled a problem and was itself an instrument of sexism and societal dysfunction.

Schuhmacher’s focus on sexist depiction comes forward even more clearly in Queen, a large painting that he completed in 1968, a year before he created Corrida. It depicts a woman’s white silhouette on a red background, only her lips rendered in bright reds as if puckered for a kiss. Otherwise completely white, the woman is quite literally a blank. Her silhouetted hands surround her breasts, which themselves take the shape of the “bonnet” of a deep blue E-type (a Series 1, as a matter of fact). The headlights positioned as her nipples. Schuhmacher used similar gestures and configurations of hands and breast in several of his works, not all of them including cars but transforming nipples into brand symbols (Mercedes-Benz three-point stars), gun barrels, machine-like rings.

I’m currently on the search for the current owner of Queen. I think I have a lead to the photographer of the painting, Rudolf Gretler, who died in 2018, and rights to his work may have been assigned to the Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv. But I’m still thrashing around a bit to find the actual holder of the painting (Rafael Schuhmacher?) and, perhaps, also the copyright.

I’m also interested in other uses of the E-type in similar ways — uses that draw upon the car’s “glam” but turn it around as social-cultural critique.

Shoot me an email if you’ve got leads or approaches to dig out some of this kind of information: technocomplex@substack.com.

Got a comment?

Tags: writing, presentation, ideation, procrastination, discovery, Patricia Highsmith, slow, pop art, social critique, protest, car culture, Hugo Schumacher, Rudolf Getler

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

An eloquent essay on what makes writers tick. Includes the “shimmering” image: Gabbert, Elisa. “Why Write?” The Paris Review (blog), July 6, 2022. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2022/07/06/why-write/.

Camera Austria International, no. 142 (2018). https://camera-austria.at/en/zeitschrift/142-2018-2/.

The pictures that you’re embarrassed to look at: Schuhmacher, Hugo. Queen. 1968. Acrylic on canvas, 220 cm x 180 cm. SIK-ISEA. https://www.sikart.ch/werke.aspx?id=14512117 and Corrida. 1969. Pencil and acrylic on Bristol board, 50 cm x 35 cm. Inventarnr. 6692. Kunstmuseum Thun (Switzerland); gift of André Boss und Irma Pastori, 2010 https://kunstmuseumthun.ch/katalog/corrida/.

And selected links from recent “daily missives” to members of the seminar:

Ingram, Andy. “Cloudflare, Kiwi Farms, and the Challenges of Deplatforming.” Columbia Journalism Review, September 8, 2022. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/cloudflare-kiwi-farms-and-the-challenges-of-deplatforming.php.

Blitz, Mark. “Understanding Heidegger on Technology.” The New Atlantis, Winter 2014. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/understanding-heidegger-on-technology.

Wilkinson, Alec. “How Mathematics Changed Me.” The New Yorker, September 6, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/how-mathematics-changed-me.

From Café Anne, a Substack newsletter: “Whatever Happened to Friendster?”

I have a bit of a lead to other resources on cars and social critique, spiced with a bit of horror, I think: Petros, George, and Deanna Lehman. Carnivora: The Dark Art of Automobiles. 1st ed. New York: Barany Books, 2007. Apparently the book accompanied an exhibition that premiered in Detroit in January 2008 concurrent with the Detroit International Auto Show. I haven't laid my hands on it yet, but Hugo Schuhmacher's work is included, I've learned.

Mark, you mentioned briefly the power of conversation, so I have to mention ours: you and I bounced back and forth via email ... surveillance, Zuboff, Crawford, Derrida ... and something in that, when processed on a long walk around town, unlocked a problem in the story I’m writing. You just never know where inspiration comes from! I’m going to bounce your e-type quest off some friends of mine. Stay tuned on that one.