A dark side of car glamour

"It might be said that Southern Californians have added wheels to their anatomy."

Read time: about 10 minutes. This week: Cars and people, a merger in art. Like, dark and macabre art. Next week: I reflect on the first year of my Substack.

How about subscribing?

This Technocomplex post lands on the final day for this fall semester’s seminar. I’ve kept class themes in mind for the posts since late August, however loosely. In part, today’s class session is a look ahead on what I’m cooking up for next year. It’s not so much an exploration of a topic relating to “our complex relationships with technology.” Cars will figure in, and how a society “decided” to admit them as an organizing technology.

And so, this post is slightly loosen from this fall’s seminar themes, as it begins to anticipate other directions that I might pursue next fall. And as such, this post foreshadows ’stack topics that lie ahead.

Time to peek at the flip side of glamorous art depicting (or peddling) the automobile, America’s truest and most beloved “pet.”

Glamour and cars

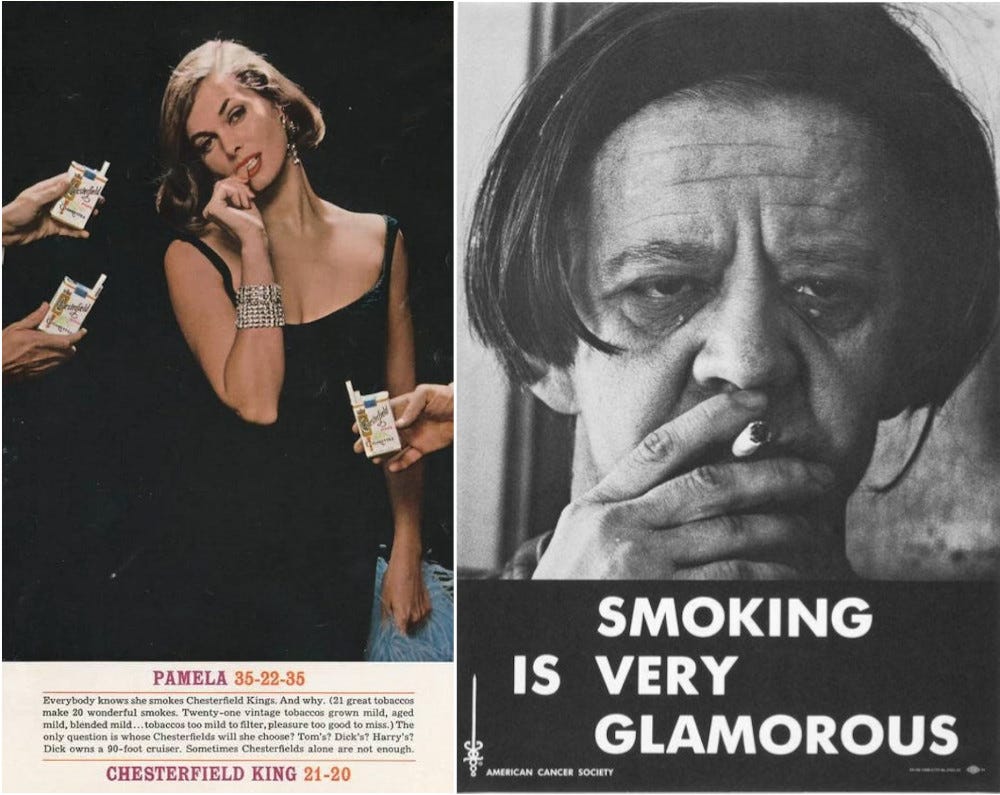

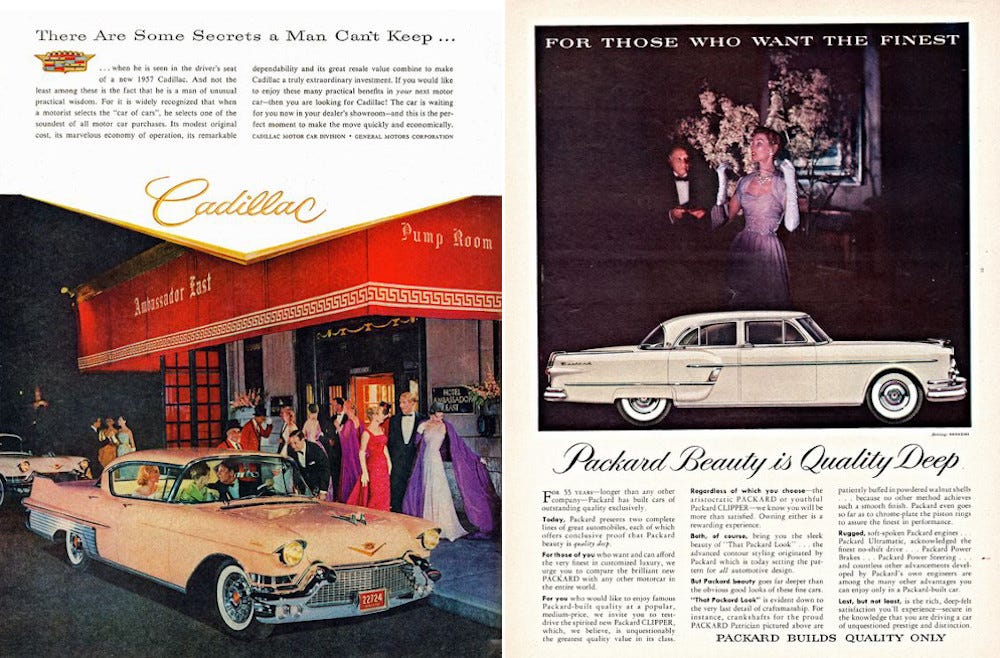

We’re all familiar with it — the trope of glamorous form (often a woman) with automobile. It’s common in car advertisements, but I think it reached its highest expression in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly and unsurprisingly in the luxury car market. Cadillac wasn’t the only car maker to tie glamorous life with their cars, but Cadillac had great coherence in its message.

The narratives are impossible to overlook. This is the good life, the life of privilege and comfort, a life absent any worry about cost. It’s beautiful and female, too. Cadillac and its competitors, including those down the General Motors division lines, elaborated on the themes, with some differentiating flourishes. Everything was smiles, curves, attractive, and, well, white. The cars? Well, they often had fins.

The Cadillac ads bring human form close to the representation of the car, as though either the car serves as a fashion accessory or the woman is an ornament for the car. Color, of course, is a powerful key. Cadillac made a series of such ads, and they enlisted high fashion designers to come up with the women’s dress. Compare the sizes of the images, and you immediately see that the woman’s image towers over that of the car, even though the car is the product.

Color unifies the human form and the machine. Through it, the car and the human body belong together — a colorful melding and close complementarity.

Glamour serves as a powerful bridge for the imagination, unifying desires and dreams with objects in the case of advertising. It transforms. It gives observers a flash of fantasy with the promise that if you own one of these, the life you imagine can be yours as well.

Uncharitably seen, glamour is a pleasing form of deception, and that’s probably why it works so well in advertising.

The dark side of glamour

Deception and dark forces have been associated with glamour from the very beginning, even though its early association with the word grammar seems innocuous enough. Our word glamour comes from a Scottish adaptation of the word in the eighteenth century, when it meant “enchantment,” a magic spell or deception. Allan Ramsey used it in this way in a satirical poem published in Edinburgh in 1721:

Like Belzie [Beelzebub] when he nicks a Witch,

Wha sells her Saul she may be rich;

He finding this the Bait to damn her,

Casts o'er her Een his cheating Glamour.When the word was coined, the glittering and shimmering illusion of glamour sped souls into Hell. And this sinister association persisted. For the next century-and-a-half or so, glamour was a matter of false advertising, often on a spiritual level.

Modern advertising has played with the deception behind glamorous depictions, as a famous magazine “public service announcement” from the American Cancer Society showed. The sinister associations do indeed still persist, though probably a bit more weakly.

A similar juxtaposition of car-glamour and car-anti-glamour came together quite dramatically in contrasting exhibitions in Detroit in 2008. Les Barany, a rather shameless impresario for unconventional art and horror, explained in an interview in October 2007, “The idea started with an invitation for me to curate an exhibition at C-Pop Gallery in Detroit, a city whose history is intertwined with the automobile history — so car art seemed like a good idea.” Barany’s playfully dark vision, laden with blood and gore, sex, and horror, informed most of his artistic selections. He said that “traditional car art is not what I had in mind,” and his curation of “Carnivora” was informed by his taste for split blood, macabre atmospherics, seamy sex, and the kind of violence you see in horrific car crashes. Barany’s Carnivora: The Dark Art of Automobiles might be described as the exhibition catalogue.

The Detroit Auto Show opened on January 13, 2008 — one day after “Carnivora” opened. Carnivora had at least one other show at L’Imagerie Gallery in North Hollywood, California, in May and June that year. Barany may simply have desired to shock and irritate Detroit Auto Show attendees with his exhibition, but his curation also serves as a dark critique of the automobile. Cars, he said, “are the only machines with which we can become one, and that can transport us to heretofore unreachable places.”

I had come into contact with the C-Pop “Carnivora” show when I was searching for information about Hugo Schuhmacher, a Swiss artist whom I have written about previously. Barany included two of his pieces in the exhibition, both silk screen prints from a limited edition collection called Frauto that Schuhmacher produced in 1971: “Hands Up” depicts chrome breasts with gun barrels as nipples held in feminine hands. The breasts reflect a red sports car. “King of Mercedes on a High Horse” is most definitely not safe for work, since it shows a woman opening her vagina to admit a Mercedes-Benz star hood ornament. These are not nice images, and they express Schumacher’s shrill critique of automobile culture with its overt appeals to sexual exploitation — the very kind that was especially lurking in car advertisements twenty years ago and before (and maybe after).

Barany’s choices reveal a similar critique of automobile culture, the very kind of culture that was simultaneously being celebrated and marketed a few blocks away at the Detroit Auto Show. Some of the choices are whimsical, like Craig LaRotonda’s sepia-toned collage-like “Back to the Future” (2005, Mixed media, 8.25” x 8.5”) which shows the movie’s “Doc” Brown, monkey wrench in hand, seated in a retro 1950s toy-like car. “Doc” faces a wrecking ball that is bound to smash into his face. Robert LaDuke’s acrylics cleanly depict puzzlingly surreal and actually quite whimsical scenes: a business-suit man lying on a road with “BUMP” stenciled on the asphalt. A 1940s or 1950s era car rolls not five feet from his feet (“Bump”, 2006, acrylic on panel, 15” x 26”).

But two images seemed particularly striking to me.

Brian Horton’s “Muffy’s Crash” (2007, digital image, 18” x 24”) plays with some of the tropes of glamour shots in car advertising: an attractive woman in fancy dress — ballet dancing garb — looks at the viewer with head cocked, cigarette smoke in a wisp surrounding her lips, the cigarette between her fingers. Her legs are splayed in rather unladylike fashion, and her arms are lacerated and bleeding. Behind her appear a car’s headlight and grill. Predominant colors are pink and red and black. In addition to creating works like “Muffy’s Crash,” Horton has built a career as a video game artistic and creative director. His clients include Disney, DreamWorks, EA, Lucas Arts, Konami, Atari, Infinity Ward/Activision, Vivendi, Crystal Dynamics/Square Enix, Dark Horse Comics, and DC Comics.

Viktor Koen’s “Carnivora No. 1” stood out to me because of one of the car parts that Koen used: a red bonnet from a Series 1 Jaguar E-type. The piece is one of two that may well have been commissioned for the exhibition, judging from their titles and low reproduction numbers (there are only five prints in existence). Koen’s imaginative work often brings together common items — doll heads, gauges, gears, insect wings, car parts, mechanical pieces that are mysterious and not so mysterious, items you might find in your junk drawer. The piece I was drawn to showed a man’s head, partially obscured — taken over, in fact — by automobile parts of various kinds. The picture shows a melding of automobile and human in a particularly disturbing way. Koen is a faculty member at the New York City’s School of Visual Arts, and his work has appeared in many major publications and in exhibitions.

Not just Southern Californians have added wheels to their anatomy

When I drive I do feel a certain extension of feeling, and despite my bride’s nervousness about getting too close to things, I do know the edges of my car. It’s a common feeling, I think, and one that has been around about as long as the car. We feel a connection with the car that is, perhaps, a bit uncanny. John Urry’s seminal article on “automobility” noted that “a Californian city planner declared as early as 1930 that ‘it might be said that Southern Californians have added wheels to their anatomy.’ The car can be thought of as an extension of the senses so that the car-driver can feel its very contours, shape and relationship to that beyond its metallic skin.” More recently, Cory Doctorow said much the same thing, although he has a larger focus on computer devices:

I’ve been at this for long enough that I had to explain to people that I wasn’t speaking metaphorically when I said that they were headed for a moment in which there would be a computer in their body, and their body would be in a computer—by which I meant their car. And, if you remove the computer, the car ceases to be a car.

The distinction of automobile and human has blurred, and it has been blurred for some time. The old Cadillac ads invoke an overlap of sorts of female image and metal vehicle. Doctorow’s description is technically accurate and implies a closer merger of the kind that Viktor Koen audaciously depicts.

“In time, will our carnal cars become vital extensions of our nervous system?” Peter H. Gilmore asked in his contribution to Carnivora, an essay titled “The New Centaurians.”

Shall we intentionally evolve our own flesh to accept enhancements made of steel, glass, and other foreign substances, bringing us to a new plateau of extended unnatural selection? Such an unholy matrimony of motor and motorist seems inevitable as our mad science unites man with machine. I think we shall then be closer kin to those anciently imagined centaurs, drunk with the wine of velocity and aroused by our ever-broadening horizons as we barrel down the autobahns, deeply excited by the journey itself.

Gilmore has been the “High Priest of the Church of Satan” for more than twenty years, but even that sinister role hasn’t blinded him to the unnaturalness of our obsession with the car, which he outlines with a peculiar fascination. The transformation he sees turns human into machine, a monstrous melding that is of a kind that the glamorous images of car advertisements only subtly suggest.

Got a comment?

Tags: cars in art, cultural critique, sexism, automobiles, Jaguar E-type, XKE, cyborg, art exhibition, Detroit, Detroit Auto Show, art gallery

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Byrd, Christopher. “Cory Doctorow Wants You to Know What Computers Can and Can’t Do.” The New Yorker, December 4, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/cory-doctorow-wants-you-to-know-what-computers-can-and-cant-do.

Some glamorous pictures for peddling the Jaguar E-type: DeLong, Mark R. “The Curves, Mostly — Glamour And The Jaguar E-Type.” Mark DeLong (blog), March 21, 2020. https://markdelong.me/2020/03/21/the-curves-mostly/.

Volume 1 includes the poem cited in the post. Ramsay, Allan. Works [of Allan Ramsay]. Edited by John W. Oliver and Martin Burns. Scottish Text Society. [Publications] ; 3d Ser., 19-20, 29; 4th Ser., 6-8. Edinburgh, Printed for the Society by W. Blackwood [1951-74], 1974.

It might be considered an exhibition catalogue produced by Les Barany. Many artworks are NSFW. Petros, George, and Deanna Lehman, eds. Carnivora: The Dark Art of Automobiles. 1st ed. New York: Barany Books, 2007.

A classic. Urry, John. “The System of Automobility.” Theory, Culture & Society 21, no. 4–5 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046059.

And, from the morning missives:

Bary, Emily. “What Is ChatGPT? Well, You Can Ask It Yourself.” MarketWatch. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/what-is-chatgpt-well-you-can-ask-it-yourself-11670282065.

Hu, Jane. “The Problem with Blaming Robots For Taking Our Jobs.” The New Yorker, May 18, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/the-problem-with-blaming-robots-for-taking-our-jobs.

Liedke, Jacob, and Jeffrey Gottfried. “U.S. Adults under 30 Now Trust Information from Social Media Almost as Much as from National News Outlets.” Pew Research Center (blog). Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/10/27/u-s-adults-under-30-now-trust-information-from-social-media-almost-as-much-as-from-national-news-outlets/.

Seabrook, John. “So You Want to Be a TikTok Star.” The New Yorker, December 5, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/12/12/so-you-want-to-be-a-tiktok-star.

Winnick, Michael. “Putting a Finger on Our Phone Obsession.” Blog. dscout, June 16, 2016. https://blog.dscout.com/mobile-touches.

“The Center for Sustainable Media.” Accessed December 5, 2022. https://sustainablemedia.center/.

MIT Sloan. “MIT Sloan Research on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning,” October 26, 2022. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/mit-sloan-research-artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning.

- and roon. “Generative AI: Autocomplete for Everything.” Substack newsletter. (blog), December 1, 2022.

- . “GPT-4 Rumors From Silicon Valley.” Substack newsletter. (blog), November 11, 2022.

- . “What Does an AI Say to Another?” Substack newsletter. (blog), November 22, 2022.

On a practical level, cars (like many other tools) give you incredible power. Go almost anywhere, fast, whenever you like. Take whatever people and things you want with you, and do it in comfort. There is a reason for their popularity.

Given the size of the United States and how much of its growth and development coincided with the automobile's rise, the USA is a little stuck -- it built for the car, with a bunch of assumptions. 100 years later, though, we're getting low on gas (having burned it all and sent it into the atmosphere), and didn't really anticipate a global population of close to 8 billion. Changing that infrastructure is difficult, and despite what some of my neighbors think, bicycles are not a reasonable option for many people in many situations in the best of circumstances, and public transit is not a serious option for many American cities any time soon.

It will be difficult to get people to give up the convenience and power of the automobile without significant incentives to change their behavior, and significant penalties for not changing their behavior. Even getting people to just switch to electric cars is difficult. (Even getting people to just wear a mask to save themselves and their families is difficult!)

The rise of the automobile also coincided with the rise in radio, television, and modern advertising. On a more symbolic level, cars are sex. Cars are freedom. Cars are an expression of who you are. (Note that you can substitute nearly anything for "cars" here, too).

Getting a driver's license was a rite of passage for many people in the 20th century. It is only relatively recently that kids have started not wanting or bothering to do it. Some of this is because their parents are much more willing to drive their kids wherever they need to go than previous generations were (to say the least).

I think of the song "Dream Cars", from Neon Neon's Stainless Style album, about John Delorean:

"Dream girls in cool cars / Cool girls in dream cars..."