Loving and naming cars

Emotional attachments we have with cars make climate change solutions more difficult. It's not all science and technology.

Read time: about 9 minutes. This week: Cars and our emotional ties with them. How we treat cars complicates changing the rules we live by. Next week: It’s seersucker season!

Under a Wikipedia article called “List of Cars characters” I noticed an editorial comment that I had not seen before. This one didn’t fit with the typical nags I’d seen strewn through many articles — such as “This article needs additional citations for verification.” The new one read, “This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience” (bold typeface in the original). The article had been recommended for deletion on August 19, 2009, but it still survives, due to a lack of consensus.

Even though Wikipedia editors seem peevish about it, the article is actually quite impressive and thorough — to a fault, if you read the “talk” pages that moderators left behind. Eighty-five characters in the Cars films (and Planes, “which is set in the same fictional universe”) appear in a long table, categorizing their roles as “main,” “supporting,” and the like — some in cameo roles in deleted scenes.

It’s one thing to admire the exertion and attention to detail in the Wikipedia entry. But what struck me more was to note an underlying enthusiasm for naming cars, even fictional ones. “We don’t name, say, our tableware or the nails and screws in our junk drawer,” I thought. “But cars often bear names.” According to one scientifically suspect survey conducted by Nationwide Insurance, about 25% of car owners said they named their cars, and women were more likely to do so, 27% compared to 17% of male respondents.

Names are a potent sign of adoption and attachment, of course. We name our children, and what parent hasn’t agonized about the choice. A name may commemorate and honor a relative, push an identity forward in history, or uniquely ornament a new life.

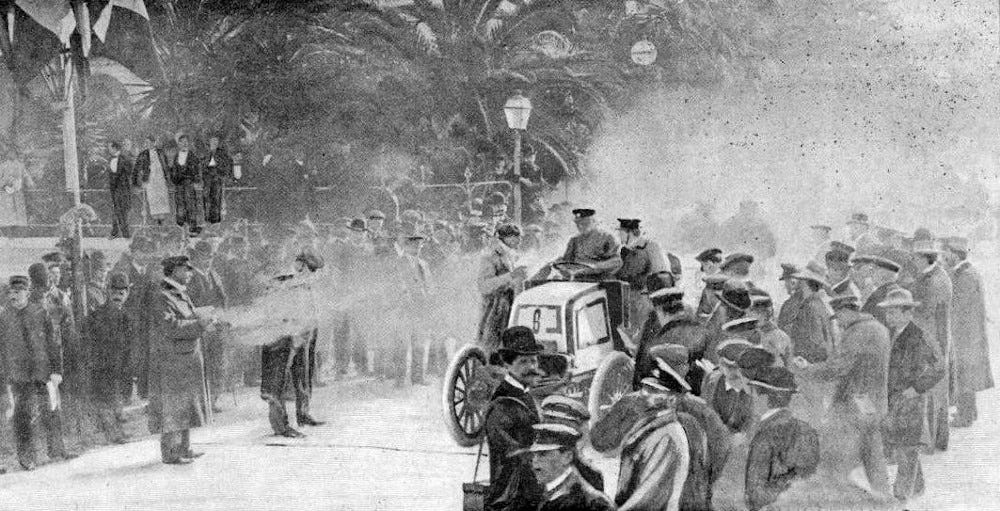

Sometimes, parents choose car names for their babies — something I found remarkable and perverse. The website Choose My Car searched for instances of car names given to children in the UK and the US between 2000 and 2018. The most common, I have to say, were rather unsurprising given that car manufacturers often took the names of their founders, and some car names were given names of founders’ children. The Mercedes Benz, for example, was given the name “Mercedes” by Emil Jellinek, a motor racer and promoter of Daimler-Benz cars. Mercedes was his daughter’s name, and he had adopted it in a car race in Nice, France, where he drove under the name “Monsieur Mercedes.”

Then, of course, there’s always the “Edsel Ford,” named after … Edsel Ford.

I found “uncommon names” the most interesting, even though they are relatively rare. They include car names that are less prone to the kind of inheritance that comes with being a car company founder. Among UK girls the name “Lexus” counts as not so uncommon — there are 181 young ladies who were saddled with it by their parents; the same name is listed for 47 UK boys. “Lexus,” it appears, is an ungendered name in the UK, but not so in the US, where some 2,910 girls but no boys were christened with it. In the US, “Tesla” outnumbers “Ferrari” quite dramatically, too, with 1,395 girls named “Tesla” (again, no boys) and a total of 46 children named “Ferrari” (23 girls and 23 boys). It’s almost too embarrassing to mention, but some US children were named “Chevy” and “Chevrolet.”

Of course, the confounding matters of name origins, not to mention questionable scientific “rigor” that might have been applied (or, more likely, not even thought about) during data collection and analysis, make it difficult to draw any sort of conclusions. But it is interesting that such an article might even appear, especially in the context of a car buying website. Its appearance underscores the association of names and automobiles.

Another thing: There is a “National Name Your Car Day.” It’s October 2, so you have time to think about your choice. The designation (but by whom?) practically makes it feel like naming your car is a patriotic duty.

Yes, and…?

The examples of scrupulous cataloguing of Cars characters, children named after car makes and models, and a designated “national day” for naming cars are edge cases. I include them here simply to turn up the volume on the weirdness of what has become a normal, culturally pervasive practice of naming machines of transport.

Why name? We name children, obviously. We name our pets. Some give inanimate objects names — really almost anything (see r/Random_Acts_Of_Amazon).

You might name an object if you’re lonely, as was the case with “Wilson,” the volleyball in Cast Away (2000). But mere loneliness doesn’t seem to fit reasons people name cars. We may name them to “own” them, but names often imply a certain independence and even willfulness on the part of the thing being named. The things have a mind of their own, so to speak, and therefore have the human qualities of stubbornness and obstinance that undermine our notion of who’s boss. That’s certainly true of old cars, since they are likely to poop out and leave us stranded. An article in The Cut notes that “one survey of listeners of NPR’s Car Talk Show, which found that the more unreliable a car, the more people were likely to attribute a mind to it. Machines, unlike humans, are supposed to be reliable; when they aren’t, we see more of ourselves in their unpredictability.” (I’m working on an unpredictable old Porsche that the previous owner named “Old Raggedy.” The name fit, but with each fix and mend it fits less and less.)

Then there is affection, emotional attachment, and perhaps a bit or eroticism, too. German journalist and novelist Hans G. Bentz described a scene in Alle meine Autos (1961) that rings true, because it’s been replayed in garages worldwide:

I retreat from the window and slink into the garage, where a certain something sits, gleaming in black enamel and chrome… I open, an expectant tingling along the spine, the steel-sheathed door and, as usual, stand there for a moment in giddy admiration. Long and broad and low, it lurks like a shell in the muzzle of a cannon…. ‘Well, how’re you doing there, Boxie?’ I ask and pat it on its broad rump (translated by Don Reneau).

As a car lover, I understand the anthropomorphism and the humor of the name Bentz gave his car. I, too, have looked back at my cars as I’ve walked away from them to cast another admiring glance.

Witnessing the debut of the Citroën DS (aka the Déesse or “goddess”), Roland Barthes described how the “cars are visited with an intense, affectionate care: this is the great tactile phase of discovery, the moment when the visual marvelous will submit to the reasoned assault of touching … sheet metal stroked, upholstery punched, seats tested, doors caressed, cushions fondled; behind the steering wheel driving is mimed with the whole body.” His phrases skirt close to the erotic.

For some cars (including, I’d say, the Déesse), such human identification is spiced with rare flair and beauty. When I spoke with a restorer friend in Colorado about his 60s Jaguar E-Type coupe that he had recently sold, he recalled, “I miss having the car around for no other reason then just go out the garage and sit in it still and look at it. Just marvel at what an absolutely beautiful piece of sculpture it is.” He caught himself for a moment in the memory. “You know, the cars were just gorgeous and literally there were sometimes when I would just go and look at it and just go and walk around it and just look at it.” He had called his car “Tweety.”

Naming a car seems entirely appropriate: they’re almost human, therefore worthy of names.

Love of cars — a problem

The world has known for a long time that the automobile is “the single most important cause of environmental resource-use” (John Urry) — including not only their greenhouse gas emissions but their use of urban resources in parking space, gnarled traffic, and sprawl. Solutions have largely been matters of automotive technology and engineering and public policy and planning. But such approaches are insufficient because they are the stuff of reason and order — or perhaps reordering — that take too little account of irrational and emotional ties that the car has with human beings individually and with society and culture as a whole.

In the 1980s, when he believed he could see the eclipse of the car age, German scholar Wolfgang Sachs wrote, “The automobile is much more than a mere means of transportation; rather, it is wholly imbued with feelings and desires that raise it to the level of a cultural symbol. Behind the gradual infiltration of the automobile into the world of our dreams lie many stories: ones of disdain for the unmendable horse, of female coquetry, of the driver’s megalomania, of the sense of having a miracle parked in the drive, and of the generalized desire for social betterment.” The “feelings and desires” root the car firmly, making a change of the status of the car in society a matter of wrenching individual identity and uprooting industry, entertainment, and modern notions of freedom. Other scholars have said much the same thing, though I think too often in journal articles that are easily brushed aside for being just more esoteric egg-headedness.

We need new prose of love and care to convey a wrenching emotional message about our beloved automobiles. For a change in culture will require a change in the lovers of cars, those who have named the beasts that sit in garages and driveways. If the change comes, it will not come because a love of cars transforms to hate or disdain. I’m not sure what the car’s place will be mid-century, but I hope the car will still have a place of fondness in changed circumstances, better ones for the earth.

But, sorry Tesla, I don’t think electric cars provide the whole answer, no matter how much we love you.

What did you name your car? Got a comment?

Tags: cars, personification, names, environmental resources, pollution, emotion, car fetishism

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

A bit turgid, yes. But well meaning and even insightful: Sheller, Mimi. “Automotive Emotions: Feeling the Car.” Theory, Culture & Society 21, no. 4–5 (October 2004): 221–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046068.

Sachs, Wolfgang. For Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires. Translated by Don Reneau. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Sach’s book is readable and steers clear (mostly) of turgid academic jargon and high-falutin’ “theory” of much other academic work on the complex relationships of human beings and automobiles.

An accessible and readable brief article on the topic: Bucklin, Stephanie. “The Psychology of Giving Human Names to Your Stuff.” The Cut, November 3, 2017. https://www.thecut.com/2017/11/the-psychology-of-giving-human-names-to-your-stuff.html.

Maybe we’re just primed to see humanness in some things: Epley, Nicholas, Adam Waytz, and John T. Cacioppo. “On Seeing Human: A Three-Factor Theory of Anthropomorphism.” Psychological Review 114, no. 4 (2007): 864–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864.

Barthes, Roland. “The New Citroën.” In Mythologies, translated by Richard Howard and Annette Lavers, 169–71. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012.

Only 25% of people name their cars? What kind of people are the OTHER 75%?! Not sure they'll ever be friends of mine...

My first car was named 'Posy', and she was an absolutely beautiful 1963 Morris 1000 4-door saloon in dove grey with limited edition duo-tone interior. She was my 21st birthday present in the mid 1990s. I still achingly miss her. She smelt of black oil, horsehair and hot vinyl.

Lovely post - thank you.

Beautifully articulated! As a massive petrol head and owner of a couple of classics, I’m struggling to accept a fully electric automotive future.

It is undeniable that the time will come when the characterful combustion engine is no more. I’m mentally preparing myself for that moment. It is a difficult but necessary change.