MoToR eyeglasses

Early 1900s eye fashion aboard the horseless carriage. Part of a series on car-related media and advertising. Lots of public domain pictures. Chicken eyeglasses, too.

Why don’t you share this post?

A curious juxtaposition: In the middle of the page, Mrs. Victor Mather, one of Philadelphia’s “prominent society women,” smiles as she sits at the steering wheel of her Autocar, her hat a stylish flourish. The rest of the page is devoted to “Hints on Valve Grinding. How it is best and most easily accomplished. Why grinding is sometimes necessary.”

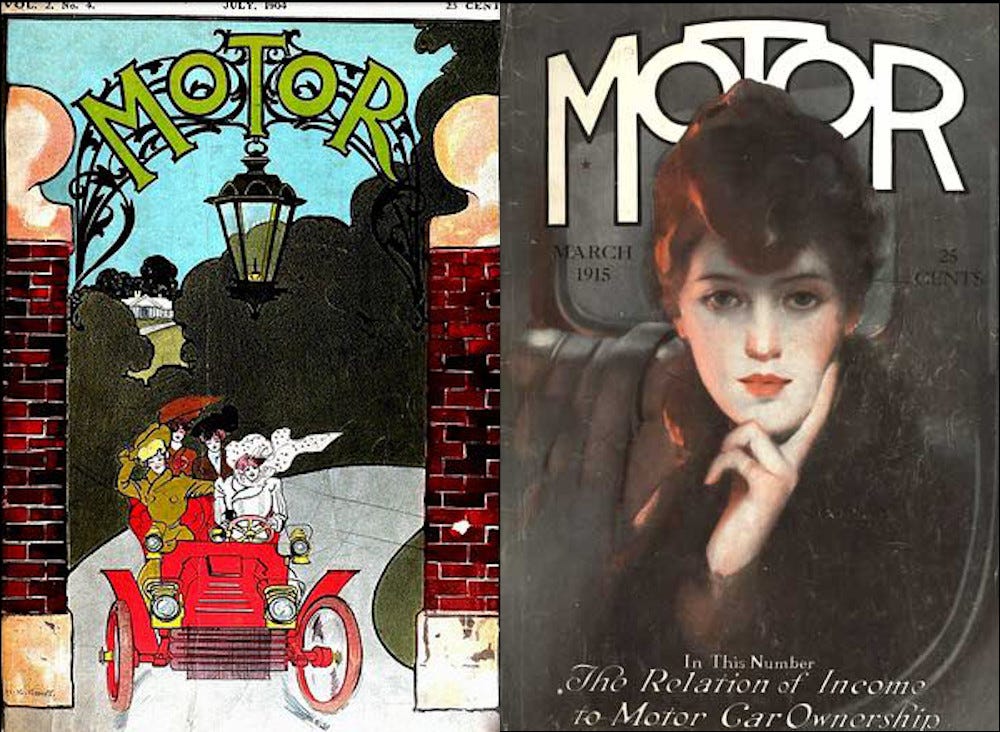

One could think that Mrs. Mather likes to grind, or at least finds it “sometimes necessary.” The page with Mrs. Mather at the wheel more likely exemplifies Motor magazine’s broad — and in this case at least, confusing — focus in 1907, when the automobile was a social signal even more than a technical triumph or a focus of continual maintenance and repair. Features in the August 1907 issue included other prominent Philadelphia women, “Correct Motor Raiment” (including appropriate motoring funeral attire), “Motorology” (a listing of races and competitive “touring” often club-sponsored), motoring accessories, and “things the motorist wants to know.” Read it carefully and you could also grind your car’s valves. Motor appeared in 1903 and still continues, primarily as a resource for the automotive industry from the Hearst publication empire.

Motor’s transformation from early twentieth-century society notices, travel anecdotes, car polemic, and technical sheet to today’s rather bland twenty-first century chronicle of automobile business reflects in part the story of automotive triumph in American society. Today, the car has long stopped serving as marker of social status — though some car models still emit some strong signals — but has become a necessity for full participation in society, which even the US Supreme Court acknowledged (Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 715 [1977]). Beyond that, the car is so attached to modern life that it has become paradoxically invisible to us. It is simply a part of the fabric of our social life and our identity as individuals.

How did early car media shape the ways that American society assigned meanings to the car? And, in particular, might the rather unsettling associations of women and cars trace some of its heritage to depictions of women in popular press of the early twentieth century?

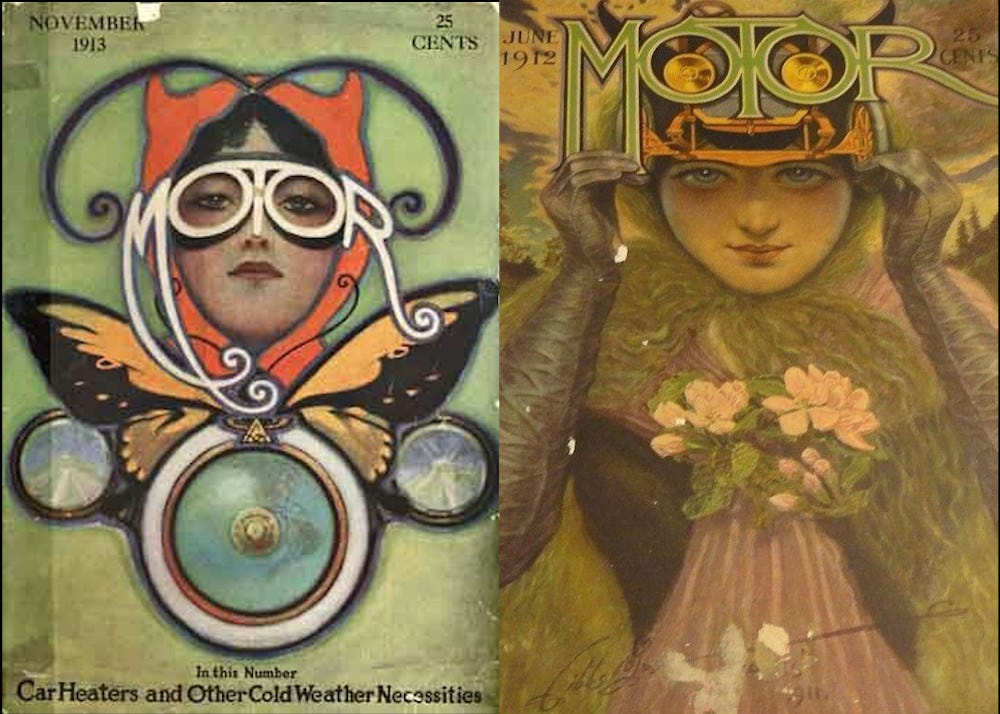

Femme fatale and the “MoToR” eyeglasses

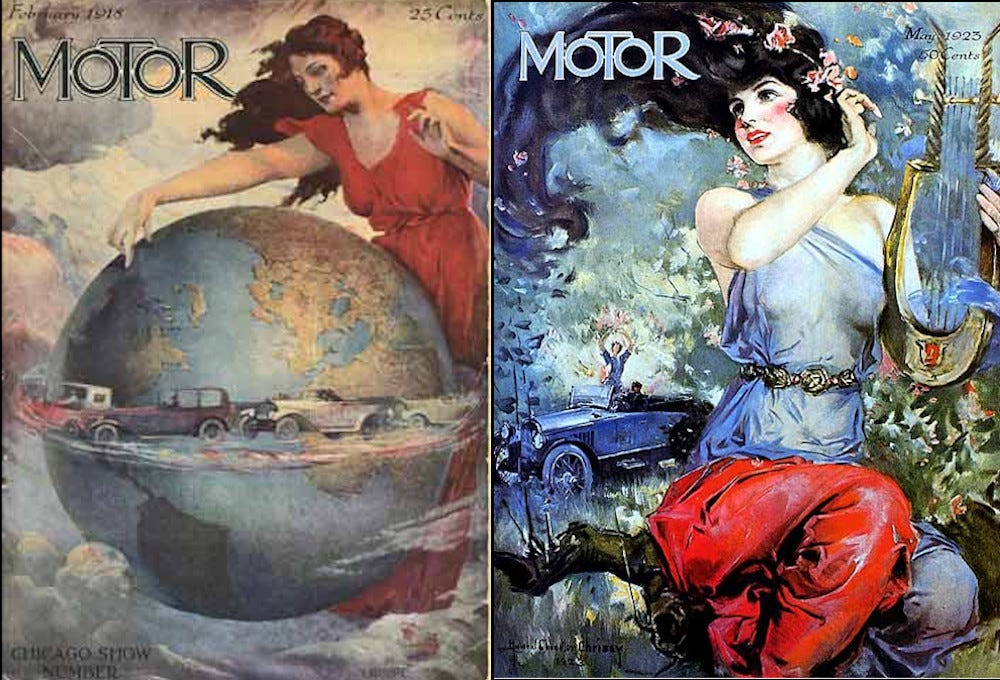

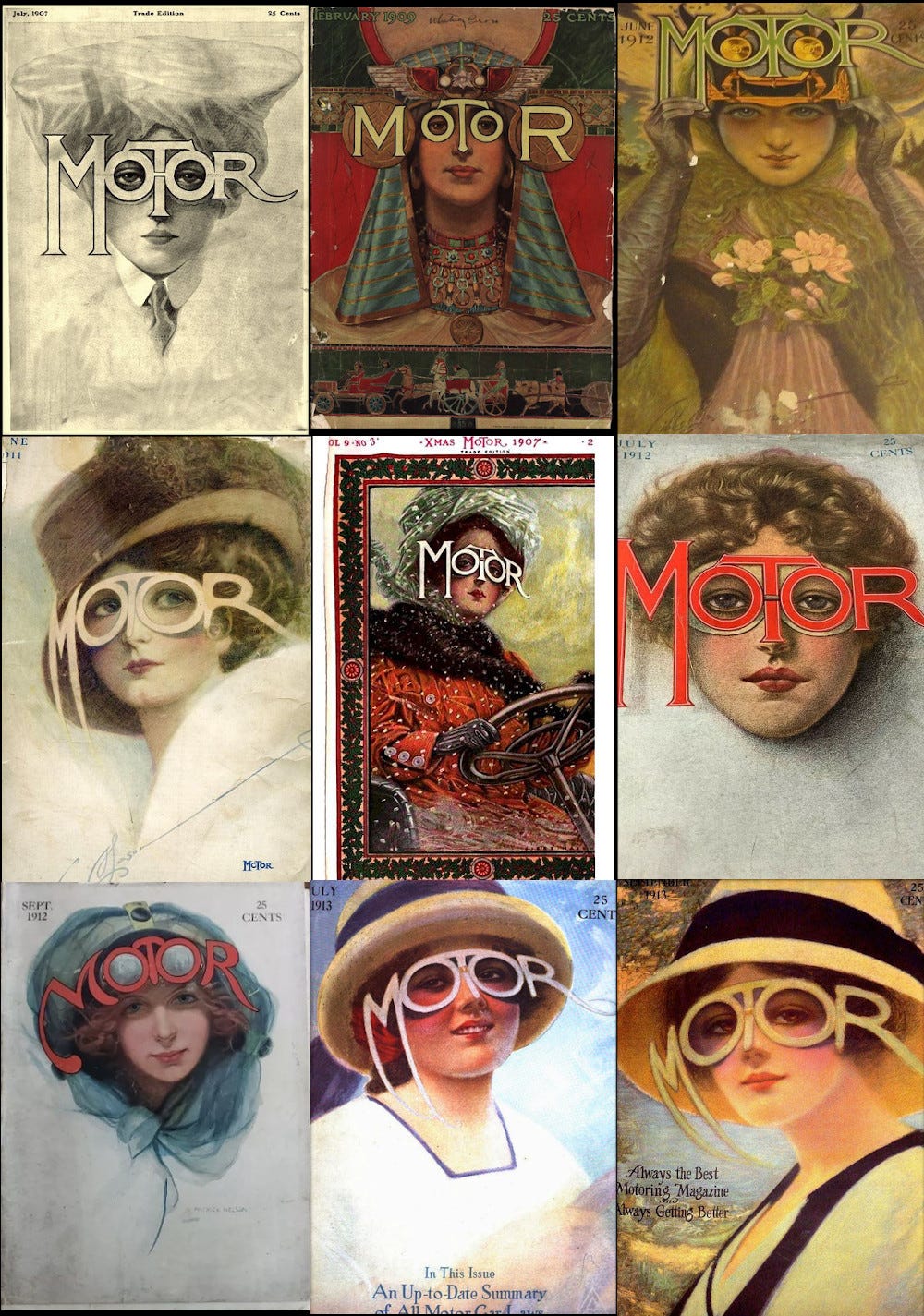

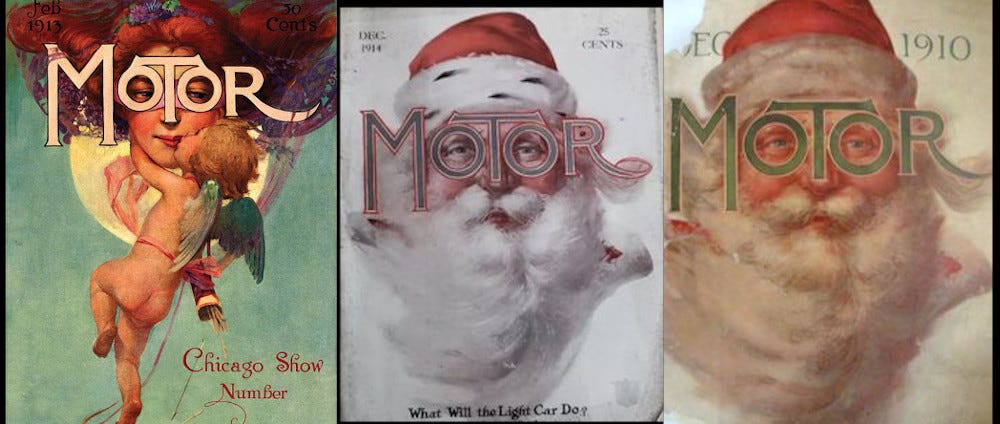

Motor’s covers from the early issues were extravagant, most of them richly colored illustrations drawn by some of notable illustrators of the time. Illustrations continued for decades on Motor covers before giving place to photographs. That was the practice for many magazines — consider, for example, covers of the Saturday Evening Post.

Motor covers frequently featured women, often fashionable dressed and ready to drive or already with hands on the wheel, and in the first two decades of the century, women were shown in heavy driving garb. Cars were often open, after all. In the 1920s and 1930s as the magazine’s editorial began to focus on industry concerns, images of women shed the bulky clothing and took on gossamer wisps. Women on Motor covers also became as ethereal as their garb, sometimes taking on the identities of fairies and goddesses.

Perhaps it was an early attempt to brand the Motor name, perhaps it was just an inside tip-of-the-hat to fellow illustrators, but for several years, Motor played with eyeglasses fashion, sometimes mixing in a devilish twist of a horned woman staring at the reader.

The MoToR eyeglasses feature appeared first in a cover from 1907 by Gibbs Mason, and other artists followed his lead. G. Patrick Nelson, Z. P. Nikolaki (“Count Nicholas Panoyotti Zarokilli Nikolaki”), and possibly Vincent Aderente fashioned eyeglasses on covers, too.

The concerted effort suggests that either the illustrators or, more likely, Motor staff shared some interest in branding, and the primary association was with women — young, beautiful, sometimes also stern, or dangerous. All four illustrators were relatively close in age and certainly knew each other: Mason was a 28-year-old when his eyeglasses cover appeared in 1907; Nelson was 36 when his lady graced the cover (September 1912). Nikolaki was 35 when his bespectacled woman appeared on the May 1914 cover. Aderente (if he did the July 1913 cover) would have been 33 for his cover.

Yes, images respond. They also shape.

Why ladies on the cover of what was clearly and, over time, increasingly a magazine about the automobile industry and technologies — including the stuff of greasy hands and bruised and bleeding knuckles?

We probably forget that the early market for cars was as unclear as it was narrow, in early days a product for the rich and privileged, as Woodrow Wilson predicted. But the energy and promise of the invention was clear to many, and production numbers bore this out: In 1900, total US factory sales amounted to about 4,000 cars; in 1923, the number jumped to 3.6 million cars (source: US Census Bureau). And yet understanding of the market aimlessly wandered in the early years of the century, both because of its early male-dominated focus and because the car market itself was actually shifting. Manufacturers looked to each other for clues about who actually would buy the things. In 1909, when Maxwell got “tremendous response” from the rural community, and others took note — and took out ads in rural newspapers and farm weeklies — without getting similarly tremendous results. That year was also the peak for the number of American car manufacturers (they were more accurately “assemblers”), at 272 firms. The market was crowded with sharp-elbowed competitors, and car makers knew that affluent urban dwellers had deeper pockets.

The feminine faces, some bespectacled, that graced Motor covers may be a symptom of this fuzzy understanding of the car market, as editors and ad men fell back to a default appeals of social standing, excitement, and sex.

It’s a mistake to look at car advertisements or Motor covers as simple responses to a market. Perhaps especially in newly formed and forming markets, advertisements and publications play an important role in fashioning the market and giving it features that attach to individual products — indeed, whole categories of products — and create associations that stick. Those associations, of course, are part of the point of advertisement: we call it an element of “branding.” Those associations sometimes become advertising tropes and play out in many ways.

The Motor covers with pretty women or scantily clad nymphs and fairies both attracted attention and encouraged an association of cars with women and sex that has played out in popular culture, media, and American identity. This wasn’t Motor’s fault, of course, but representative of larger forces. The covers echoed ways that cars were presented to society and imprinted an identity, a set of associations, that continue to function for an entire industry. In the case of cars, the association of women, glamour, and sex were early appeals that became enmeshed in what cars mean in American society. Those cultural cues were matched and deepened by more overtly political powers to steer public support for infrastructure and laws supporting an automotive culture.

In part, feminine associations of the car stemmed from ladies wearing MoToR-ing eyeglasses.

Tags: Motor Magazine, depiction of women in media, automotive history, early twentieth-century history, Gibbs Mason, Z. P. Nikolaki, Vincent Aderente, G. Patrick Nelson, Howard Chandler Christy, magazine illustration

Final note: This post has a narrow focus on Motor, and I discovered that not all that much has been written on the magazine’s early history. Online examples of covers are available on Pinterest, but whole issues are less available that one would think. The University of Michigan, thank goodness, has digitized its early collection for Hathitrust. My guess is that no library has a complete set of the publication’s early decades, and examples are pricey even if they’re available. The covers themselves might also be fairly rare, since issues I looked at from University of Michigan and the University of Chicago mostly lacked them. Perhaps they were pinned up in early twentieth-century garages and shops.

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Finding a way in early car industry: Devanatha Pillai, Sandeep, Brent D. Goldfarb, and David Kirsch. “When Does Economic Experimentation Matter? Finding the Pivot in the Early History of the Automobile Industry.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, June 12, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3199544.

Sharon Cockrum’s And Steve Filip’s Pinterest collections of Motor covers: https://www.pinterest.com/sshockley11/motor/ and https://www.pinterest.com/stevefilip/car-art-the-golden-age-motor-magazine/ together make up the most complete collection on the web, at least that I’ve seen. One thing to note: You can see the shift of the magazine as it establishes its market. It becomes more clearly focused on the car industry — manufacture, selling, and repair — as time progresses. This Cockrum’s collection goes into the 1950s.

Good article on Motor cover illustration: Hedgbeth, Llewellyn. “Motor Covers: The Art of MoToR Magazine.” Second Chance Garage. Accessed October 8, 2021. https://secondchancegarage.com/motor-covers/The-Art-Of-MoTor-Magazine-1.cfm.

Motor magazine on Hathitrust: “Motor.” Motor; the Automotive Business Magazine. Garden City, N.Y. etc. Publisher: Hearst Corp. etc. Accessed December 31, 2021. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000046489.

Public Domain Day: Jenkins, Jennifer. “Public Domain Day 2022.” Center for the Study of the Public Domain, Duke University School of Law, January 2022. https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2022/. All praise the public domain!

Professor Shill’s (somewhat shrill) attack on law’s support for the car: Shill, Gregory H. “Should Law Subsidize Driving?” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, May 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3345366.

Car snap-shot: Delahaye 135M. Even sitting, it appears in motion. I want one.

Chicken eyeglasses (yes, really): “Chicken Eyeglasses.” In Wikipedia, April 8, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chicken_eyeglasses&oldid=1016770570.