Out to pasture

... or to the knacker. The shift from equine world to automotive world in Puck, a humor magazine from the early twentieth century.

Read time: about 10 minutes. This week: Ambiguous future of transport, as seen in the first decade of the twentieth century. The passing of the horse. Next week: I can’t believe I’m actually writing about my notebooking.

The Boulangerie offers glimpses of what’s in a warm place rising or already in the bakery oven on the ground floor of the TC Tower headquarters. This past week, just a single amusing patent of Lego men. I only announce when something happens in the Boulangerie with my Mastodon loudspeaker: @mrdelong@mastodon.online.

Share this one with someone who drives a car, please. If you got this from a friend who shared it, how about getting your own copy? A subscription is free, and it’s only another email.

This past week, I have been stuck between two worlds: One is the familiar and routine world of the horse, since I clean stalls and drag hay to pastures. I am a master of the manure fork, and I know the difference between orchard grass and alfalfa. The other, a modern invention: the diesel truck. Mine was attacked by marauding squirrels about two weeks ago, and the little buggers managed to chew a hole in a nylon fuel feed, which of course was about the most inconveniently located part on the whole tr-ucking apparatus. I got the part and managed to replace it. The truck runs, but it requires me to constantly bleed the fuel line to get the thing started in the morning. I’m hoping that persistence will eventually clear out the air, but the bleeding’s not stanched yet.

The upshot: For now, horses sure feel more constant and dependable than my old truck, and the aroma of manure is really no worse than the stench of diesel. I can get into the house after cleaning a stall, but Bond Girl Bride shoos me out the door if I cross the threshold wearing a diesel-tainted jacket.

The passing of the horse

Stuck as I am between the pooping horse and pooped out truck, it seems appropriate that this week I look at the “passing of the horse” in the early twentieth century. It seems an obvious switch to us today — this exchange of horse for car — since much of today’s world thinks of automobiles first when it comes to modes of transport. In 1900, that wasn’t the case, of course, even though the car had been noisily rolling on some urban streets. Between 1840 and 1900, the equine population grew six-fold. In 1900 the US counted 21 million horses, and the 1900 US Census counted a bit over 76 million people. The horse was the engine of the economy, a true gauge of horsepower.

If the horse population exploded in the sixty years before 1900, it just as dramatically depleted in the sixty years that followed. In 1960, there were just three million horses counted. (People, however, became more numerous; the US population more than doubled from 1900 to about 179 million.)

In 1900, everyone saw a horse regularly, but rarely, if ever, saw a car. In 1960, everyone saw a car regularly, but rarely, if ever, saw a horse.

The turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century of course heralded the switch, even though the days of the automobile were few and the car market excruciatingly restricted to the wealthy and upper middle class. In the first decade or so, uses of the newfangled noisemaker seemed similarly restricted: cars were playthings for enthusiasts.

But the passing of the horse was forecast nonetheless.

“What fools these mortals be!”

John Pughe’s “The Passing of the Horse” appeared in the humor and satire weekly magazine called Puck after the prank-playing sprite in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The magazine thrived on political satire and biting pieces. It presented rather unvarnished critique, often tarnished by racist and anti-semitic depictions which are out-of-place today but that were hardly remarkable at the time. Puck was started in 1876 in St. Louis, Missouri, eventually relocating to New York, where the Puck Building still stands. In 1918, Puck ended its long publication run.

Illustrations were often rich in detail and color because of the magazine’s use of then cutting-edge color lithography presses. I have been interested in the ways that media shaped and were shaped by the automobile, and Puck illustrations have been particularly useful — they depict the ambiguities of the car and do so in a direct and bold manner. Puck was a satire magazine, so genteel politeness and nuance discretion were hardly priorities among the editors. The fact that the car was such an important innovation in New York and other American cities made the automobile an inviting target for satire.

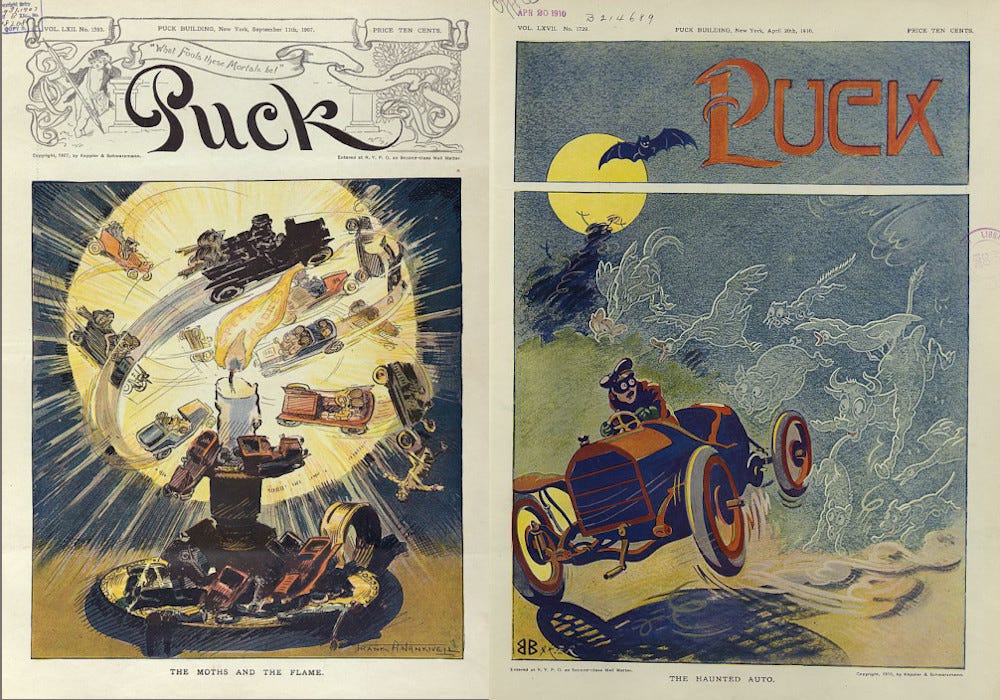

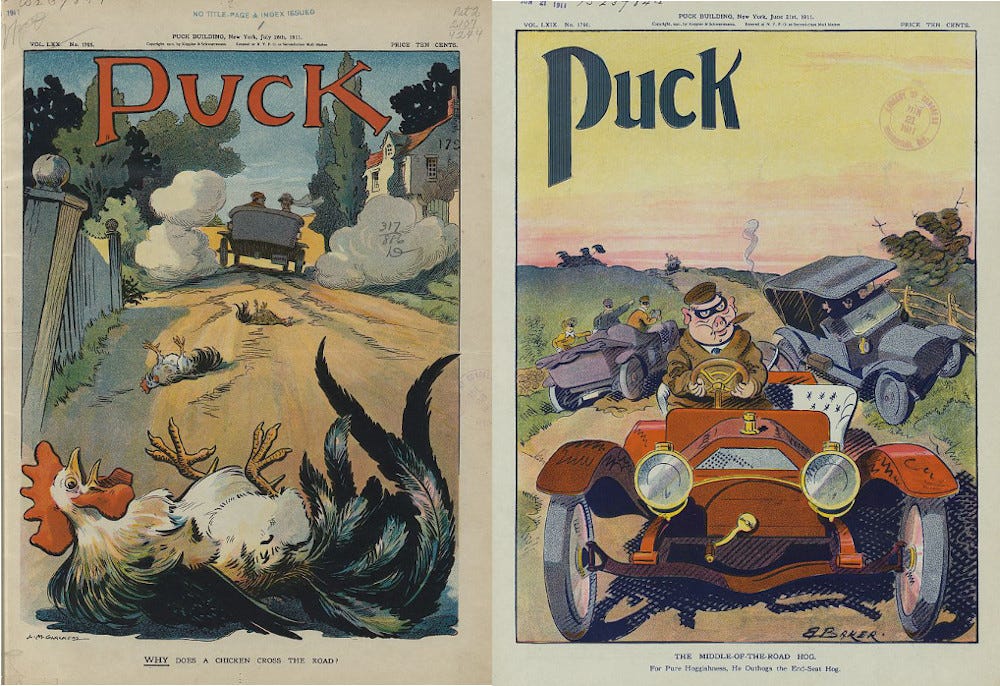

In the early years of the twentieth century, Puck’s illustrations considered how the car would change life in the United States, including the car’s influence on economic life, the impress that the car would have on rural America and the use of roadways, and tragic and wryly humorous depictions of car obsessions and the graces of driving rules and etiquette. The magazine’s illustrators were skeptical that the car would drive into America without changing much other than transport, and they had the task of entertaining and provoking their audience in satire. Some illustrations were quite dark, even cynical. Frank Nankivell’s cover in 1907 compares the cars and drivers to moths circling a flame, transfixed before crashing and burning. Bryant Baker’s “The Haunted Auto,” cover illustration for a 1910 issue, showed animal specters, presumably victims of the road, chasing a fearful driver. Albert Levering’s centerfold in a June 1910 issue depicted blinkered masses sacrificing homes, savings, valuables, and even themselves before “the gasolene chuggernaut” — a monstrous car that had laid waste to the landscape.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

The car was the environmentalist’s dream … in 1900

I may think that sifting and lugging about 150 pounds of manure is work, but on the scale of a normal day in New York in 1900 that load is but a speck of sand. At turn of the century, the math of manure added up to, well, a back-breaking load of horseshit: In 1900, on any single day in New York, the city’s 100,000 horses deposited about 2.5 million pounds of manure on the streets. That’s well over 900 million pounds a year. London, then the world’s largest city, lived through “The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894,” during which the Times of London speculated that if trends continued, “In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.”

Unsurprisingly, the automobile was welcomed as a way to clean up the mess emitted from just below the horse’s tail. Indeed, the clean up happened by the new century’s second decade when cars tootled on city streets and horses had gone to pasture. Unknown then was the mess that would poof from the tailpipe of the car.

Of course, the car-driven economy surpassed what the horse-powered economy could deliver. The untiring car was, eventually, more reliable and speedier. Automobiles also increased the range of movement. Farmers increased the number of vendors and purchasers of farm products that they dealt with, creating competition and greater efficiency. Markets broadened. People began to travel farther and more frequently than in the days of the horse. Geographically bound systems expanded as well — for example, the one-room school, which served students within a small region, could give way to larger, more comprehensive schools drawing from a broader region and providing more opportunity to students.

Benefits like these quickly became apparent, either because they immediately became manifest or were promised in the near future. But Puck illustrators tended to draw other visions of the world of the car, often with human foibles at the center. If the countryside was transformed by new transportation, the countryside suffered as well, usually at the hands of clueless or vicious drivers.

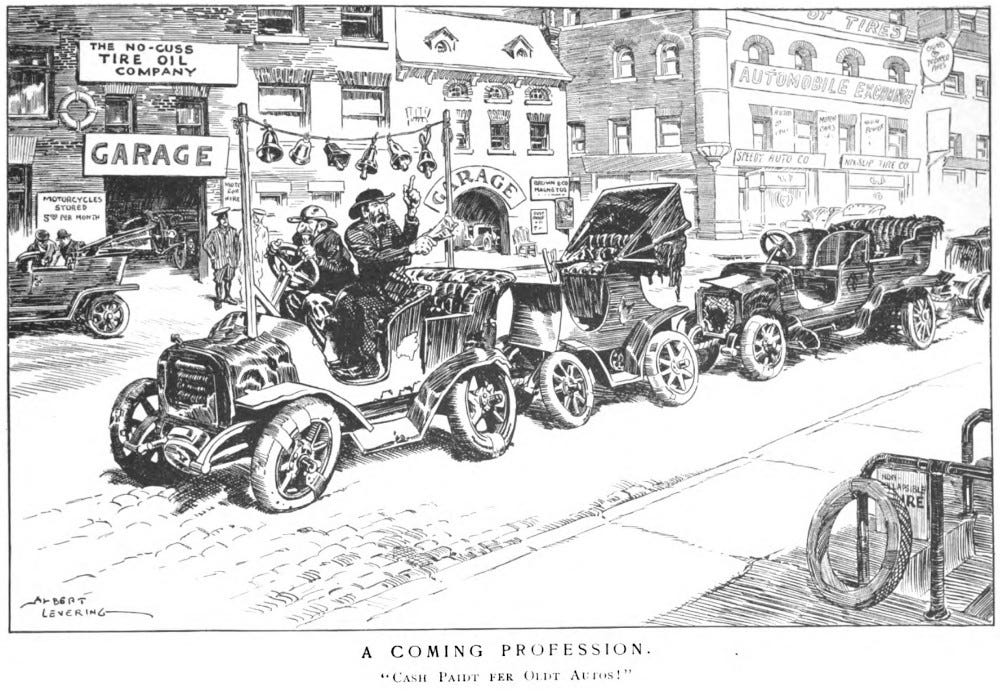

A frenzied nation of Mr. Toads led Albert Levering to think of an entirely car-based local economy, where traders and businesses served automobiles and their needs. His cartoon that appeared in Puck showed a line of dilapidated cars trailing two representatives of “a coming profession” — car-era versions of “knackers” who bought near-dead horses or gathered carcasses for hides, bone-meal, glue, and whatever might be salvaged. Behind the procession: only car repair shops, parking facilities, tire and fuel stands, car dealerships are visible.

A change in Puck’s view, just before Hearst took it over?

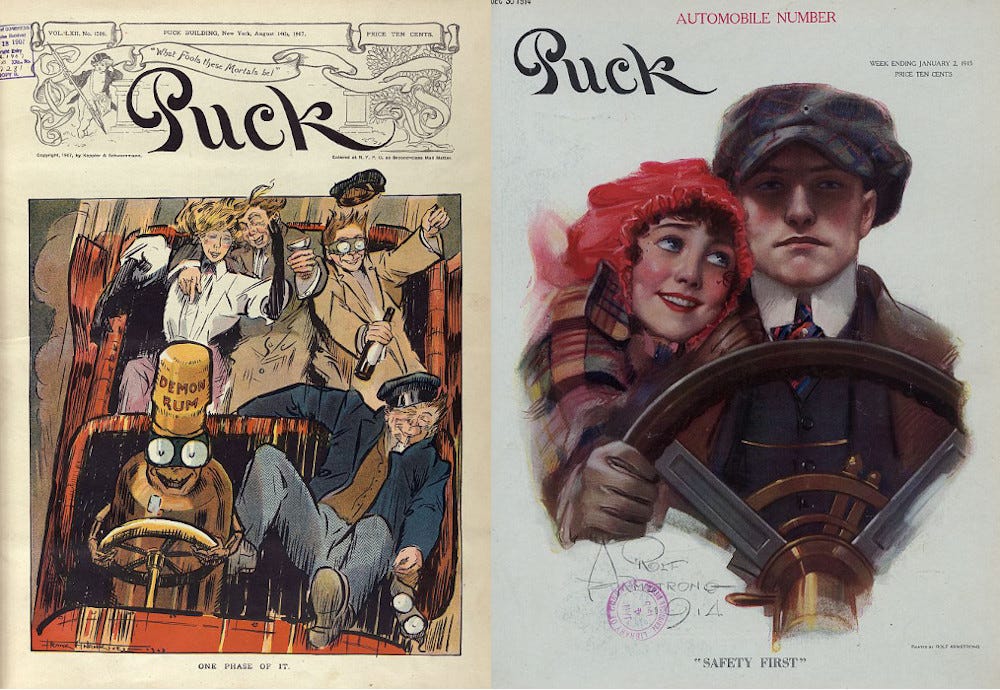

Human foibles are the stuff of satire, and Puck’s motto provides the guide for its abiding focus: “What fools these mortals be!” But the car persisted, and maybe the mortals learned some lessons by 1915, including the perils of drunk driving. The fact that the New York International Motor Show had taken place in January, and had done so since 1900, may have meant some additional magazine revenue in an “automobile number,” too. Take a look at the two covers below, separated by seven years. William Randolph Hearst, owner of MoToR Magazine, bought Puck in 1916, but perhaps in Puck’s waning years, commerce played a bigger role than it had before.

The car was the future, and it would remake American life and even the nation’s entire landscape. It would also “emancipate” the horse. In a 1907 issue of Harper’s Weekly, Winthrop E. Scarritt closed his essay on “The Horse of the Future and the Future of the Horse” with these words:

The motorcar is to emancipate the horse, and it is to solve many problems that cannot be enumerated. In short, the automobile is to become the ready, tireless, and faithful servant of man throughout the world where civilization has a home or freedom a banner. Yesterday it was the plaything of the few, today it is the servant of many, tomorrow it will be the necessity of humanity.

Got a comment?

Tags: car, horse, culture, transport, Puck, illustration

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

According to an American Horse Council Foundation (AHCF) survey, in 2003 there were about 9.2 million horses in the US. The nadir for horses was in 1960, the peak of the auto age. Lots of good information about horse population in this article. Kilby, Emily R. “The Demographics of the U.S. Equine Population.” In State of the Animals, IV, edited by Deborah J. Salem and Andrew N. Rowan, 1st ed., 175–205. Public Policy Series. Washington, DC: Humane Society Press, 2007. Available at http://www.americanequestrian.com/pdf/US-Equine-Demographics.pdf.

A view from the early twentieth century. Scarritt, Winthrop E. “The Horse of the Future and the Future of the Horse.” Harper’s Weekly, 51 (March 16, 1907): 383, 402. Hathitrust from Univ. Michigan.

Imagine nine feet of poo. Johnson, Ben. “The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894.” Historic UK. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Great-Horse-Manure-Crisis-of-1894/.

Puck lives, but this one’s really, really different. The new one adores the wealthy and the powerful, while the old one would have skewered them. Malone, Clare. “The E-Mail Newsletter for the Mogul Set.” The New Yorker, December 2, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-communications/the-e-mail-newsletter-for-the-mogul-set.