Separated by more than a century, two musicians share a complaint

Rick Beato and John Philip Sousa agree on a "menace" to music and to human creativity even though they never met.

“This guy nails it IMO.” That was the message below a Youtube link. Normally, I’d be wary of a link accompanied by such a cryptic gloss, but it came from a friend and colleague so I clicked. Destination: Rick Beato’s YouTube video posted June 25, 2024, on his “Everything Music” channel. Beato launched into his talk, his white hair combed back, hands waving like a modest conductor as he stood in what might be a 1970s living room. I could easily imagine that his jazz studies students at Ithaca College came to love his New York accent and his urgent wit.

“The Real Reason Why Music Is Getting Worse,” the video’s title, could signal a revelation of a conspiracy—the “Real Reason”—or offer another Old Man Yells At Cloud variety of crotchetiness. But by the time I finished watching, I had to agree with my guitar-playing, guitar-collecting friend: Yes, Rick Beato “nailed it.”

Beato thinks AI is corroding today’s music, lulling the human spirit and inventiveness by making it too easy to make music and too easy to consume it—of course, doing all this while stealing from musicians, too. In many ways, the story has already been told, as the replacement of skills by machine has long been a feature of the transformations of life and work over the past century and more. Beato’s complaint, however, may be more urgent than before. Maybe, as they say, this time is different.

Beato balances two aspects of today’s rapidly transforming music technology, drawing his argument into two “acts”: “Music is too easy to make” and “Music is too easy to consume”—both headings essentially framed as judgments, not as observations. Technology lies at the core of both.

“Act One” outlines the development of music technology and how it has changed musicianship in recent decades. But overshadowing the corrosion of skill set in motion by drum machines, amplifier algorithms, Auto-Tune, for example, Beato claims that AI wears the crown as the most seductively imperious technology. Services like Udio and Suno replace musical skill and musical imagination, he says, undermining human creativity and the human work that creativity requires.

He draws from his email messages: “I get about twenty of these a day,” he says, “and they always start, ‘Rick, I wrote a song that I think can be a hit. I used AI to hear it because I know nothing about making music.’ That’s literally from an email I got yesterday.”

Beato’s objections boil down to three points:

“creative dependency on technology [that] limits the ability of people to innovate,”

“the homogenization of music,” and

“quality versus quantity” (which he calls “a big, big thing, okay?”).

Music being too easy to make means too much of the same music is made, “making it harder to find really exceptional things.” Because of the creative dependency there’s likely not much exceptional to listen to, anyway.

“Act Two” is a matter of too much ease as well. With 100,000 songs added to streaming platforms last year—“more than one song per second for the entire year,” Beato notes—so much is at users’ fingertips that the value of an individual song drops to nearly nothing. “Think about this,” he implores. “All of the music that exists—or at least that’s been uploaded to Spotify or Apple Music—is available for $10.99 a month…. For the price of what we used to pay for one album.” And then he injects what might be a bit of Old Man nostalgia: “There is no sweat equity put into obtaining it, having it be part of your collection, having it be part of your identity of who you are. ‘These are the bands I believe in. These are the artists that I love, and I’m going to share it with my friends…’.”

Rick Beato’s nostalgia actually isn’t solely about music. It extends to—and maybe heavily relies upon—cultural and social meanings of music.

A band musician chimed in against earlier “mechanical menaces”

Over a century ago, a different technology applied to music elicited a similar response. The technology was the phonograph and other music recording devices, and the man voicing a bitter lament was John Philip Sousa. Yes, that Sousa—a musician for bands very different from the ones that Rick Beato plays in and produces.

In the September 1906 issue of Appleton’s Magazine Sousa’s florid and sarcastic prose laid out “the menace of mechanical music,” claiming, as Rick Beato does over a century later on YouTube, that new music technologies degrade musical talent and, even more galling, leave composers out when it comes to profit. “I am quite willing to be reckoned an alarmist, admittedly swayed in part by personal interest, as well as by the impending harm to American musical art,” Sousa admitted. “I foresee a marked deterioration in American music and musical taste, an interruption in the musical development of the country, and a host of other injuries to music in its artistic manifestations, by virtue—or rather by vice—of the multiplication of the various music-reproducing machines.”

Sousa feared musical deskilling and displacement of musicians and music teachers. When “automatic music devices” take the place of musicians in the home, he claimed, “[t]he child becomes indifferent to practice, for when music can be heard in the homes without the labor of study and close application, and without the slow process of acquiring a technic, it will be simply a question of time when the amateur disappears entirely, and with him a host of vocal and instrumental teachers, who will be without field or calling.” Technology limits musical innovation by stunting musical skills.

Music teachers and musicians weren’t the only to suffer economically; copyright law worked against music composers as well. In 1906, as Sousa put it, copyright law meant that “the composer of the most popular waltz or march of the year must see it seized, reproduced at will on wax cylinder, brass disk, or strip of perforated paper, multiplied indefinitely, and sold at large profit all over the country, without a penny of remuneration to himself for the use of this original product of his brain.” Sousa mocked an appeals court decision that spared makers of music rolls for player pianos the need to pay composers, a decision later upheld by the US Supreme Court (White-Smith Music Publishing Company, Appt. v. Apollo Company, 1908). In the end, composers got their royalties only after the Copyright Act had been amended in 1909. (Likewise, in his YouTube video, Beato discusses hoovered-up original music feeding AI models, economic forces, warped copyright enforcement, and business shenanigans that support today’s music industry. He also includes a conversation he had with Ted Gioia about AI fakery.)

Not a repeat of history, but a rhyme

These two historically distant musicians complain similarly, but the technologies that prodded them differ in degree, perhaps in kind as well. Sousa’s complaint finally had to do with the distribution of music and, more vehemently, with the rules that robbed him and his fellow composers of fair remuneration. Beato’s complaint is a bit less defined, if for no other reason than that “AI” itself continues to be a cipher for, well, practically everyone, if we’re being honest about it.

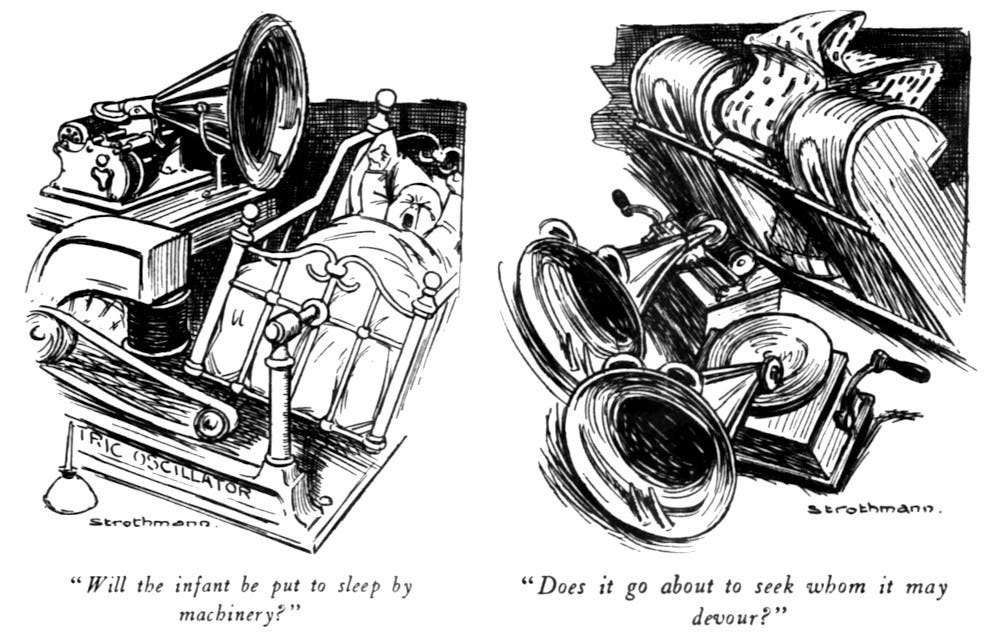

Both Sousa and Beato focus on consequences and meanings of music, in effect pushing our attention to the landing places of music: the physical realities of human experience, both individual and social. Both musicians find the mechanisms wanting. “[N]ow, in this the twentieth century come these talking and playing machines,” Sousa wrote, “and offer again to reduce the expression of music to a mathematical system of megaphones, wheels, cogs, disks, cylinders, and all manner of revolving things, which are as like real art as the marble statue of Eve is like her beautiful, living, breathing daughters.” Beato point to same-sounding and derivative “homogenization”; his “Eve” is not made of marble but of an accreted slurry of what was made before.

Sousa’s argument in Appleton’s Magazine placed music within human situations—courtship, the baby nursery, the battleground, the country dance—to juxtapose live and mostly amateur performance against the musical device. Though the mechanical menace had obvious deficiencies in reproducing the sound of a human performance, he chose to point to contexts that the “tireless mechanism” transforms—and not for the better. An example: “The country dance orchestra of violin, guitar, and melodeon had to rest at times,” he observed, “and the resultant interruption afforded the opportunity for general sociability and rest among the entire company. Now a tireless mechanism can keep everlastingly at it, and much of what made the dance a wholesome recreation is eliminated.” At a June 1906 Congressional hearing on proposed amendments to the Copyright Act, Sousa told the committee, “When I was a boy … in front of every house in the summer evenings you would find young people singing songs of the day—or the old songs. To-day you hear these infernal machines going, night and morning.” After the room erupted in laughter, he added, “We will not have a vocal cord left.”

Rick Beato invokes social and cultural contexts, too, though within limitations that the “infernal machines” place on him a century after Sousa had railed against them. He recounts how building his record collection as a teen meant “bagging groceries at Topps Grocery Store in Fairport, New York. You actually had to expend energy.” And for what? Listening to the Led Zepplin album alone in his room? Sometimes, perhaps, but Beato recalls what might be described as a ritual of music, involving the process of scraping together cash, “going to the record store, buying the record, bringing it home, listening to it a bunch of times, going over to your friend’s house, sharing it with them.” Sweat equity secured the value of the music and, importantly, opened teenage life to conviviality and friendship—a use of recorded music that even cranky Sousa might value.

Music was a collective tissue bringing people together, perhaps in awkward unison but also in a cultural community, however small.

Of course, Sousa only contended with mechanized music reproduction; Beato also has to deal with AI “composition.” The circle of music making and music consumption is complete in the twenty-first century, and humans, standing aside the whirling machines, serve only with idle ears and fingers swiping across screens. Today, AI music-like sounds can be extruded to serve as a personalized Muzak squirted into your ears. You don’t have to bother anyone either, except for the occasional earbud spray.

It may be—I certainly hope it will be—that habits of human sociability and conviviality will apply the brakes on a rush to AI’ed everything, including music. Sousa high-mindedly claimed that music is an “expression of soul states; in other words, of pouring into it soul.” Beato at the end of his video implores us to “just listen to the music. Let it flow over you … and try to experience music like you used to. Or, if you’re young, try to experience music in the way that we used to.”

Today’s AI may swallow Muzak and background music libraries. More success may prod human hands to hold instruments again. Human ears will detect that something is missing and will be motivated to “pour into it soul.”

Got a comment?

This article was previously published in 3 Quarks Daily on July 15, 2024.

Tags: music, artificial intelligence, ai, creativity, art, consumer, creator, automation, skill

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Beato Rick (Producer). The Real Reason Why Music Is Getting Worse. YouTube video. Everything Music, 2024.

Sousa’s 1906 article: Sousa, John Philip. “The Menace of Mechanical Music.” Appleton’s Magazine 8, 3 (September 1906), pp. 278-284. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_appletons-magazine_1906-09_8_3/page/278/mode/2up.

The Supreme Court decision that Sousa would lament: WHITE-SMITH MUSIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, Appt., v. APOLLO COMPANY., No. 209 U.S. 1, 28 S.Ct. 319,52 L.Ed. 655 (US Supreme Court February 24, 1908). https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/209/1 (Legal Information Institute).

An account of the Congressional hearing on the Copyright Act in a publication for the “talking machine” industry: “Protests Against Provisions of New Copyright Bill.” The Talking Machine World, 2, 5 (June 15, 1906). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/talkingmachinew02bill/page/n246/mode/1up.

This is really interesting, Mark, on a couple of levels (to me, anyway). First, I never want to be a Luddite, and there is a sense to which both of your figures are resisting technology because it is uncomfortable for them or dislocates their existing practices, so I’m a little bit reluctant to side with them. And yet … I find myself really sympathetic! I find my appreciation for all forms of art to be greater when I have to work for it, and I’d say this both as a consumer and as a creator. I’ve tried incorporating GenAI into my practices as a writer. It makes me feel like I’m sleeping with the enemy. Same as a consumer. I appreciate all art more when I can deeply appreciate where the artist is coming from. So I like the way you’re pushing at this tension and I think I’m ultimately with you on how you’re seeing it. Second, I sense your attempt to be more direct and accessible as a writer in this piece, and I like it. Nuff said!

Is “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness” a favourite album because it’s awesome, or because it was the first album I bought after raising the money through a slog of a flea market table one sunny Saturday in 1996? (Or both?) Really enjoyed revisiting this piece, Mark.