Shaping the shapers

We humans are tool makers, shaping our environment. Tools shape us, too, often imperceptibly and with unintended consequences. Can we shape our shapers?

Read time: about 8 minutes. This week: Messy garage, stripped cars, smartphones and un-smartphones. Next week: Some reading is hard. And that’s good.

Share this post with a friend.

My garage is a monumental pile of stuff, always accruing and getting donations of items from my sons, who come out to the garage to tinker and wrench on their cars. This past weekend, another car appeared in the middle bay — a thirty-some-year-old Acura Integra stripped to its bare necessities for the sake of speed. Comfortable it is not. Colin Chapman of Lotus Cars provides the pithy motto: “Simplify, then add lightness,” and the new addition to the Scuderia DeLong expresses it well. (Loads of T-shirts bear the motto.)

The contrast of garage surroundings and the stripped old Integra struck me especially, probably because I’d been reading Kyle Chayka’s The Longing for Less: Living With Minimalism. While the car doesn’t look like some bare-walled, clean, “minimal” surface, the point isn’t about aesthetics. It’s about weight.

There is, perhaps, a somewhat strained connection between pop-culture “minimalism” (Chayka doesn’t like it) and race car lightening. Marie Kondo, who has emerged as a major figure in cleaning up in the past years, implores clients and the readers of her books to toss anything that doesn’t “spark joy®.” For the retrofitters of old cars destined for the track, the rule can rhyme: Remove it, if it doesn’t help speed. Chapman’s Lotus Engineering motto lives, and perhaps even aligns somewhat with “KonMar” — Marie Kondo’s handle.

The Chapman approach that serves for the car in my hopelessly messy garage and Kondo’s neatnik method both have to do with making choices about things, and how, and for what we choose to have them. Chapman’s motto is pretty easy to understand, given that mass complicates speed. Kondo’s “sparks joy®” decision point is murky, or perhaps it simply evidences a whole miasma of intentions, controls, dreams, and desires that people have in life. People want to be happy in some way — what if throwing stuff away could do the trick? (Kondo has a website, too, where you can buy more stuff to help you get organized.)

In an interview around the time when his book was coming out, Chayka said, “I think having a conscientious relationship, or a conscious relationship, with stuff around you is good, like thinking about what you own, but some people have turned this into a kind of mania for living with nothing or living with as few objects as possible, and embracing empty space. That makes me uncomfortable.” His worry: the point of removing stuff, for some, changes into its own kind of “mania” and “cultural sickness.”

When you don’t entirely know what stuff can do … later, especially

The obsession with stuff challenges us to consider not only how we choose and regard the things we surround ourselves with but also — and probably more profoundly — what sort of lives we want to live, what sort of lives we ought to live. It’s not just a matter of emptying space or arranging socks in drawers (as a Wall Street Journal reviewer of Chayka’s book put it). For the KonMar enthusiasts, you discard your way to a sparkly life, though it’s good to know that each removed item is ritualistically thanked before it hits the bin.

Happiness might not be the same as sparkle.

Improvement of life and its meaning raises the stakes of owning things or, for that matter, using services. Downstream consequences aren’t always easily apparent either, especially when you don’t have a clear picture of the underpinnings of, say, a new technology. How do you know whether the TikTok algorithm will send you into the pit of despair or a sea of plausible-enough misinformation or a pathway towards hours of scrollingscrollingscrolling — all as a result of algorithmic operations of the service and your unknowing, naïve use of it? How do you anticipate that your smartphone might distract you from important things happening around you, while also giving you reports of events taking place continents away?

Second-order (or, heaven forbid, nth-order) thinking is hard, and when we install a new app because we heard something interesting was happening on it or get a new thing that promises great things, we usually don’t think of consequences of that decision … or the consequences of the consequences. Initial outcomes lead to others and that greatly complicate decision making, especially since an initial (first-order) decision may have consequences that are unappealing but that has very positive consequences at the second- or third-order (or even later).

Shaping those things that shape us

In response to second-order complexity, we might conjure qualifications and restrictions — guardrails to help us avoid falling into a pit of despair. Take the example of the old Integra. Decisions that accord with the Chapman's adage to simplify and lighten can result in changes that actually endanger drivers — a trade-off of hazard and speed. It's entirely possible and maybe even tempting to lighten important structures in order to “simplify, then add lightness.” The cost, of course, is safety of drivers and the integrity of the machine. For these reasons, rules apply that run contrary to “adding lightness,” in effect overruling or at least qualifying Chapman’s motto. Other concerns and aims (like health and well-being) limit the push for speed on the track.

These kinds of modifications to rules and guidelines emerge gradually, for the most part, as we use technologies, though with today’s items like smart phones and their apps, a complete understanding is confounded by opaque business goals or uncharted psychology of social media (for example). We hold an iPhone without understanding the massive and invisible infrastructure that enlivens the thing. We open an app without clearly seeing the business framework that supports the technology and profoundly influences the ways that its service is presented to us in order to make money. For many, the goal is user “engagement,” and that may change our relationship with the device or the app.

Who among us has not felt a nagging need to check phones or email? Who hasn’t wondered whether the devices we’ve surrounded ourselves with have amounted to greater distraction rather than greater “connectedness”? As he was writing his book on mimimalism, Kyle Chayka noticed that “I couldn’t resist the pull of my iPhone and the latest social media updates or messages from friends…. This craving was simultaneously boring and overwhelming. The constant baseline of noise created an addiction for more that was fundamentally unsatisfying to feed, much like eating potato chips.” — An apt metaphor, that one, I think. To counter the “craving,” Chayka evaded: “I would turn the Wi-Fi off on my laptop and move my phone into another room so I couldn’t grab it in a moment’s weakness. I chose to write in spaces that didn’t have internet access….”

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

So far, I’ve seen two approaches that people use to tame the urges that Chayka mentions, and I believe there will be more that emerge in the future as we develop ways to manage the perils that come with the powers and privileges of new communication technologies. One of the approaches is akin to Chayka’s attempts at evasion or avoidance. Rishikesh Sreehari once used his smartphone “9+ hours a day, which was not clearly healthy” so he did something about it. His approach was a matter of configuration settings and getting a phone with a smaller screen. “I no longer watch very long content on my phone as the screen is too small!” Aside from the change in equipment, Sreehari’s methods amount to behavioral restrictions — no games, no notifications, use “airplane mode” when using a phone for photography, and “do not use your smartphone on the toilet.” His article lists several other interventions. Recently he’s praised the “importance of single-purpose devices in a distracted world.”

Here’s a device that fits the definition of single-purpose. It’s an “un-smartphone … You know … for making CALLS.” And it’s definitely retro, since it uses a rotary dialer and a mechanical ringer — a bell! I actually think it might be stylish. (Available for pre-order, since the kits are due to come out in November 2022.)

The first Un-smartphone, which was 3G only, went viral a couple years ago. It’s a project from Justine Haupt, who wanted something to replace her flip-phone. (Talk about primitive!) Haupt said in a Wired interview from 2020:

I wanted physical keys or buttons I could push for every function and not having to guess whether or not it was actually going to do what I told it to do. You know, when you hold down the power button — is it turning on right now? Is it turning off? I have a switch. It’s a toggle switch, it’s either on or it’s off. That’s it. I just wanted to control the technology. I think people have gone too far acquiescing to the standards of dealing with smartphones.

Could I make the switch to an “un-smartphone”? Right now, probably not, since I don’t really like “making calls.” But the device is simple, and it’s appealing. I’m good enough with kits, too.

It’s takes a while of experimentation, cultural pattern-setting in etiquette and practices, and product modification before new things find their way comfortably in the shifting sands of human society. With smartphone technologies, we’re in early days of a transition, and we’ll see — and I hope guide — the kind of society and culture that emerges around technologies like the smartphone.

Got a comment?

Tags: technology, freedom, choice, control, culture, unintended consequences, smartphone, telephone

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

“KonMari | The Official Website of Marie Kondo.” Accessed June 28, 2022. https://konmari.com/

Been, Eric Allen. “‘Minimalism Should Be a Radical Idea’: Can Kyle Chayka Change the Meaning of the 21st Century’s Most Misunderstood Word?” Vanity Fair, January 24, 2020. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2020/01/kyle-chayka-longing-for-less-interview.

Well done podcast on unintended consequences of technologies. Students in the seminar this fall have this on their list. “Unintended.” Online audio. The Digital Human, BBC Sounds. BBC Radio 4, June 13, 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00187gd.

Sometimes it’s good to look at an essay that chops itself off at the knees. Here’s one that could stand a grumpy editor or a frank living room discussion: Allenby, Brad. “Choose at Your Own Risk.” Slate, March 4, 2015. https://slate.com/technology/2015/03/how-technology-is-changing-our-choices-and-values.html.

Interview with Justine Haupt, creator of the rotary un-smartphone: Goode, Lauren. “How a Space Engineer Made Her Own Rotary Cell Phone.” Wired. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/justine-haupt-rotary-phone/.

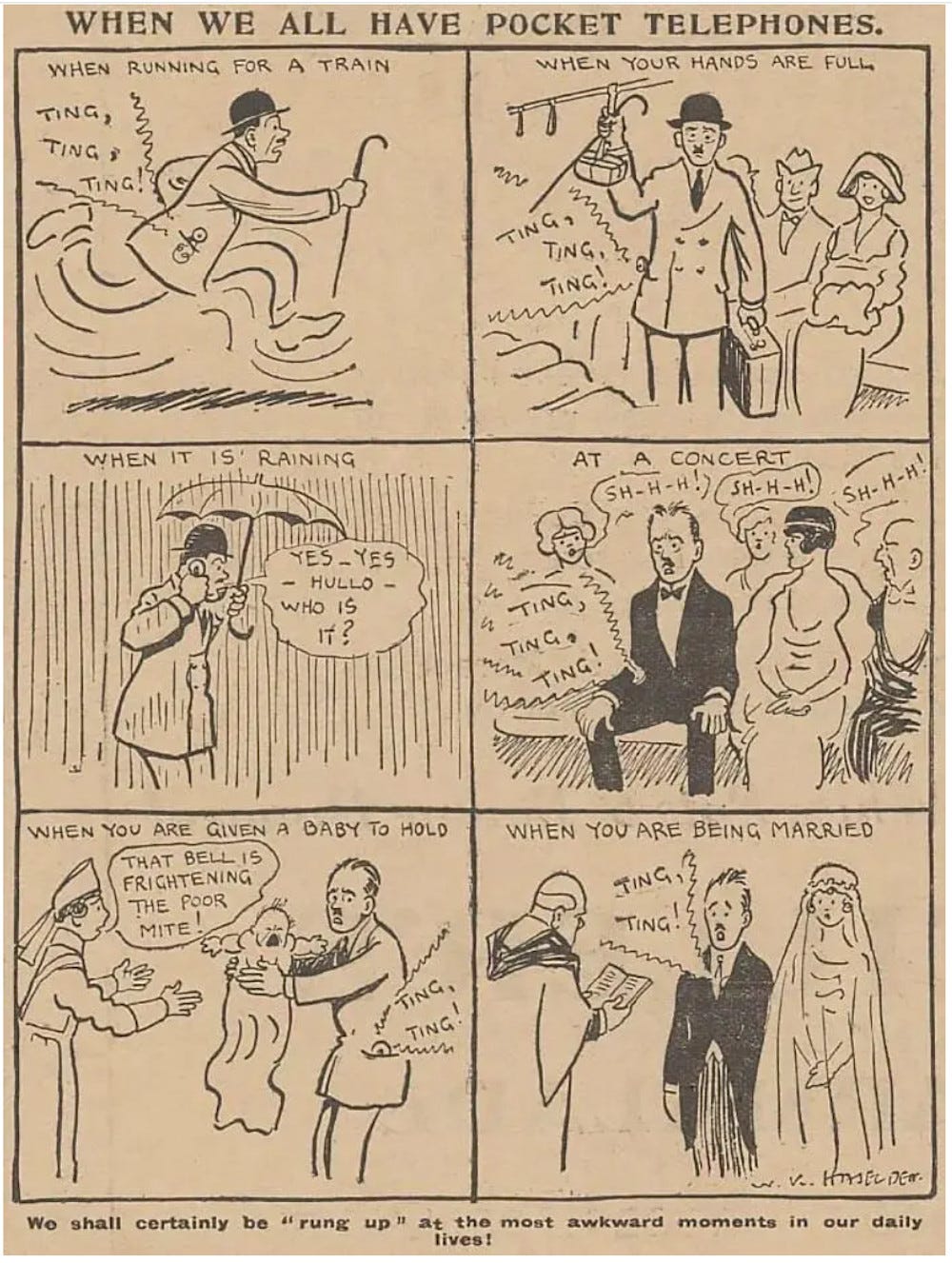

Old timey pocket telephones: Dorn, Lori. “A Prescient Comic Strip From the 1920s That Predicts the Inconvenience of ‘Pocket Telephones.’” Laughing Squid (blog), July 4, 2022. https://laughingsquid.com/1920s-pocket-telephones-cartoon/.

No doubt that our digital tools shape our behavior in their default mode - we have to purposely change to custom settings to avoid this. But on the other hand Ì'm a fan of multi purpose tools, even if I don't use each capability.

You might appreciate WRENCH VR: http://www.wrenchgame.com/