Kim and Kylie don't like algorithms

OMG! Strange attractors of TikTok and its algorithms swirl around social-graphed platforms.

Read time: about 9 minutes. This week: Social media changes, and how the tweaks show where we fit into the picture. Next week: I welcome some students who I’ll be working with this fall and outline some of the topics we’ll discuss.

I do think that I’ll be returning to social media in a future post. It’s a rich area, constantly changing.

Meta (formerly Facebook) looks panicky, but then practically anything looks knee-jerky when it’s reported on Axios, with its penchant for bulleted items and closely cropped thought. Instagram’s scroll changed so much that sisters Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner noticed and reshared a complaint from photographer Tati Bruening (@illumitati): “stop trying to be tiktok i just want to see cute photos of my friends.” Together the Kardashian/Jenner sisters have around 690 million Instagram followers, or, put another way and assuming the followers are all flesh-and-blood, a bit shy of nine percent of the world’s population. A related change.org petition started by Bruening has hundreds of thousands of signers.

Instagram took note and, after huffing a bit and some equivocation, modified its newest algorithm. At least for now.

Kyle Chayka noticed the same thing that the famous-for-being-famous sisters did, and he’s far more knowledgable about the underpinnings, since he’s on the home stretch on a book on algorithmic life that’s due to come out in 2024. “If you haven’t noticed, Instagram has gotten terrible lately,” he wrote in his Substack newsletter. “My main feed is overwhelmed with recommended posts and videos from accounts that I don’t even follow. Instagram Stories, which was once a haven of real-time moments from friends, is now a similar melange of videos, ads, and brand promotions.” He blamed Instagram algorithms, and he suspected the reason: “It might be spiking engagement for Instagram as its parent company tries to make all of its products more like TikTok, but it alienates users.”

Social media always churns, but heat from TikTok seems to have sped up algorithmic paddles coursing through social media goo.

Of course, Instagram’s tendency toward TikTok-iness isn’t just a competition of algorithms. Though Instagram’s algorithm change “alienates users” like the Kardashians and Chayka, the change is grounded in a battle to secure attentions of a younger audience — the “Gen Z” market that has found Facebook and Instagram less compelling than have the platforms’ older audiences. The rub for Zuck: Gen Z is the future; and Boomers, well, they make up a fading past, followed closely by Gen X. It could be that Gen Z doesn’t care that much about social connection, but it could also be that associating TikTok with social media platforms is assuming too much.

TikTok might just be an “entertainment platform,” as they’ve claimed, a not a place for social clusters. Of course, that doesn’t mean that TikTok won’t disrupt the socials.

Algorithm attraction v. tug of the “social graph”

The offerings from Meta and ByteDance, TikTok’s corporate owner, contend over attention, and not over the means of capturing attention, which after all amount to tactics. The real treasure and the strategic focus is minutes and the data that might be distilled from “engagement” with their products. That elixir of data is further refined into ad sales and, perhaps, other forms of payback, given the breadth of TikTok’s Hoover-like suckage of personal data and Facebook/Instagram’s similar hunger for personal tidbits to feed its ad-directing algorithms.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

TikTok uses an endlessly tweaked algorithm to select videos for users, but Meta’s Instagram and Facebook have relied on the power of the “social graph,” the map of connections between users however users define that connection, “friending” or “following.” Twitter uses a social graph as well, though its user base remains smaller than the Facebook behemoth.

In part because they share the anchor of social graph, Twitter and Facebook have influenced each other’s development. “By 2011, Twitter, following in Facebook’s footsteps, passed the milestone of a hundred million users. Facebook, of course, noticed this new competitor’s fast rise and began to make adjustments.” Cal Newport wrote, “Between 2009 and 2011, Facebook increasingly moved its news feed away from chronological sorting and toward an emphasis on popular posts. Then in 2012, it added a retweet-style Share button on its mobile app, enabling the Twitter-style exponential spread of third-party content through the network.” Newport believes — and I think rightly — that “platforms like Facebook could be doomed if they fail to maintain the social graphs upon which they built their kingdoms.”

Still, Tiktok’s algorithm challenges the hegemony of the social graph.

“The choice to tie TikTok’s content to an algorithmic curation system is what gives the platform its power — it is a place of endless content catered specifically to your interests,” Chris Franklin said in an Errant Signal video about TikTok. He observed that TikTok “removes context — temporal context or satirical context…. It is an infinite stream of best guesses to match us with stuff, and if it guesses wrong and causes some damage along the way? Oh well. A robot did it. Nobody’s accountable.” Franklin also thinks that adding TikTok-iness to the likes of Facebook and Instagram isn’t such a good idea, but for reasons different from Newport’s: “[T]he fact that this is the system that so many social platforms are looking to head towards should be met with some degree of skepticism. Creators no longer control audiences and audiences no longer control what they see.” His view looks at users; Newport’s considers the effects on the platforms themselves.

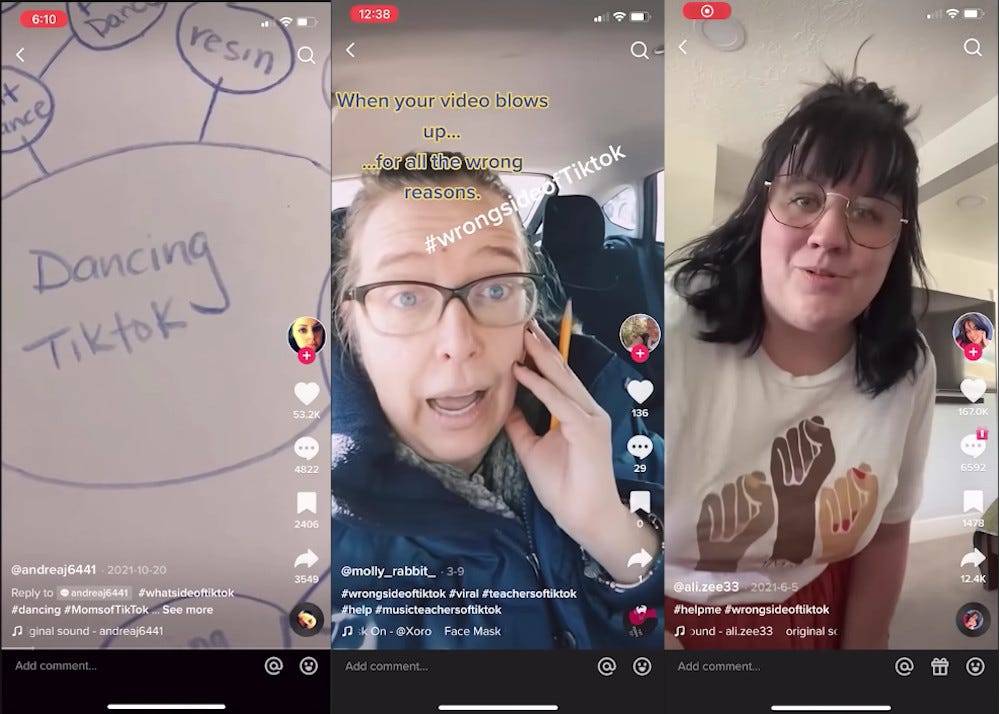

Actually, I’m more deeply skeptical than Franklin, since neither creators nor audiences actually control much of anything on social media platforms, and haven’t ever really. If anything, users are more thoroughly controlled than they think, just more profoundly and transparently on TikTok. TikTok’s algorithm makes mistakes, sending TikTokers into the #wrongsideoftiktok with sometimes humorous but also demoralizing results. The algorithm picks your audience (or a “side”), but it can’t always pick your friends.

Pressures of algorithmic life

With all the old mythology of “art for art’s sake,” you might think that artists might be among the last to fall into a platform’s vortex. You’d be wrong. In her interviews with artists, University of Sheffield researcher Sophie Bishop found that “each artist’s work is contextualized based on their personal profiles and not by their participation in art-specific institutions and practices.” And so, they have to shape their social media identity in addition to doing their art. “Artists are beholden not only to art markets — from which they once could keep a safe personal distance even as they depended on it — but to the principles of search-engine optimization, as filtered through the successful practice of influencers.” Bishop found that doing social media has become part of the art business and has even dictated artistic practices:

When demands on artists are structured not only by the conventions of the art world but by social media’s affordances (and how these have shaped audience expectations), everything about an artist’s practice can be affected. Many of the artists I spoke to confirmed this, detailing how they optimized many different elements of their practice to be visible on Instagram, including their art’s content and form, drawing on research into digital marketing strategies, discussions about how algorithms work, and personal hunches based on their own experiments [italics added].

Bishop discovered that many artists are in fact overwhelmed having to do the job of artist while also developing “content” — and a visible identity — on social media. “They are obliged to produce both art and a portrait of themselves as an artist,” she explained. “This means trying to master forms of communication that may not have much to do with their primary craft.”

Of course, artists / influencers who produce content for social media platforms (as opposed to using platforms for visibility of their artistic work) surrender even more artistic freedom to media platforms’ algorithmic overlords. For those whose canvases are social media platforms, the situation can be even more dire. Brooke Erin Duffy, Annika Pinch, Shruti Sannon, and Megan Sawey contend that “while cultural producers have long reckoned with the unpredictability of market demands and audience tastes, today’s precarity is largely an upshot of platform capitalism, rendering creators beholden to Silicon Valley’s every whim and vagary.” It’s not only inscrutable algorithms, either; the whole social media landscape quickly changes, meaning that artists can lose everything if they hitch their wagons to the wrong horse. “Over a span of mere years, some creator-centric platforms like TikTok and Clubhouse launched or evolved while others (e.g., Vine) seemed to vanish overnight.”

All is flux and Facebook has reason to fear the future.

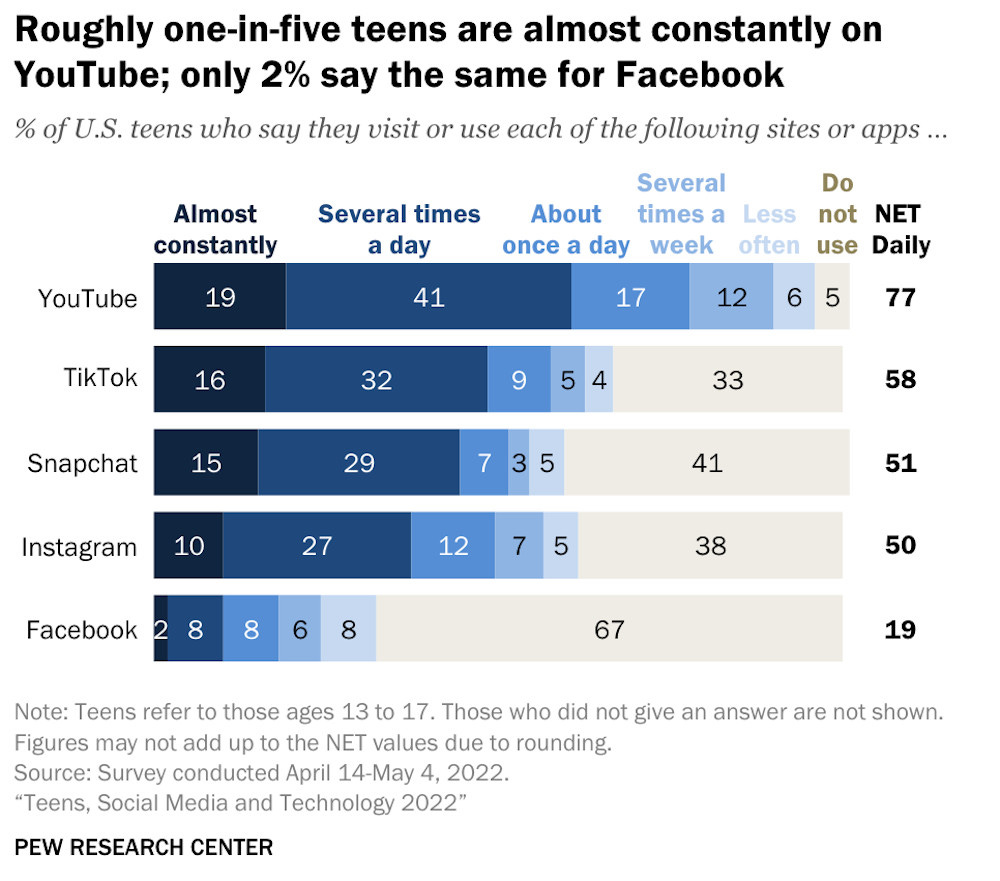

For the past three years, I’ve asked the first-year college students in my seminar on “our complex relationships with technology” to assess their use of social media, and I have seen students drift away from Facebook and become more ardent TikTokers and Instagramers. Last year, about 18 percent of the students had no Facebook account, which was a bit of a shock to me. The year before, all had an account. It’s not just a matter of having an account on a service. It’s mainly a matter of diminishing time spent using it. Last year, the most frequently used services in my small poll were TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat, all three regularly, even constantly used.

My survey has been informal, providing a quick study to encourage discussion among the students in the class. On August 10, the Pew Research Center released the results of a much more rigorous survey conducted in April-May 2022 that sought to get a picture of “Teens, Social Media, and Technology 2022.” It offers a detailed view of social media behaviors among teens (13-17 years old) and compares 2022 results with results from a similar survey conducted in Fall 2014 and Spring 2015. The complete report is available for download.

It’s a never ending topic…

I’ll be returning to the topic of social media in the future when, of course, the landscape will have changed again, probably unpredictably. I’m becoming more interested in the notion of “authenticity” on social media, evidenced by the rocketing uptake of BeReal, the French app that tells you when to take a picture and leans on users to comply. BeReal may be seeking authenticity and unstudied, unfiltered representations of the lives of its users. The more interesting question to ask is how users’ behaviors are being manipulated and brought into the whole apparatus of photography. An algorithmic take-over, one could say, that a couple of philosophers even anticipated back in the last century.

Got a comment? Are you disturbed by Instagram’s shifting sands? Use TikTok? Have you every been on the “wrong side” of TikTok? Are you using BeReal (or vice versa)?

This post was edited in January 2024 to update when Kyle Chayka’ Filterworld was to be released. It is due out in mid-January 2024, not fall 2023 as reported in the original post.

Tags: social media, algorithm, influencer, algorithm, media, artist, authenticity, representation

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

If you can stand bullets, Axios sometimes delivers: Rosenberg, Scott. “Facebook’s TikTok-like Redesign Marks Sunset of Social Networking Era.” Axios, July 25, 2022. https://www.axios.com/2022/07/25/sunset-social-network-facebook-tiktok.

Kyle Chayka is working on a book called Filterworld that will be published by Doubleday in January 2024. He’s looked at social media algorithms and their influence, and he has written about the topic in his Substack and in The New Yorker (linked in this Substack post):

Platform Gotterdämmerung? Newport, Cal. “TikTok and the Fall of the Social-Media Giants.” The New Yorker, July 28, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/tiktok-and-the-fall-of-the-social-media-giants.

A pretty thorough and revealing piece of survey research. You can see why Mark Zuckerberg might be getting antsy: Vogels, Emily A., Risa Gelles-Watnick, and Navid Massarat. “Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), August 10, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/.

TikTok as a “search engine” conveys something of the protean quality of the platform. It’s not Facebook, and maybe it’s not just an “entertainment platform”: Pogue, Wanda. “Move Over Google. TikTok Is Gen Z’s Go-To Search Engine.” Adweek (blog), August 4, 2022. https://www.adweek.com/social-marketing/move-over-google-tiktok-is-the-go-to-search-engine-for-gen-z/.

Well, uh, maybe everyone needs to try to be an influencer now. Bishop, Sophie. “Influencer Creep.” Real Life, June 9, 2022. https://reallifemag.com/influencer-creep/.

…and if you’re an influencer, you’re likely screwed, or at least scared: Duffy, Brooke Erin, Annika Pinch, Shruti Sannon, and Megan Sawey. “The Nested Precarities of Creative Labor on Social Media.” Social Media + Society 7, no. 2 (April 2021): 205630512110213. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211021368.

An English professor lives in a TikTok mansion for a while, where he watches the natives and even makes a TikTok video: Swanson, Barrett. “The Anxiety of Influencers.” Harper’s Magazine, June 2021. https://harpers.org/archive/2021/06/tiktok-house-collab-house-the-anxiety-of-influencers/

Interesting statistics on TikTok since its beginning, compiled from various sources. Iqbal, Mansoor. “TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2022).” Business of Apps, August 15, 2022. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/.

Long (51 minutes), but good video unpacking Tiktok: TikTok: Life on the Algorithm. YouTube video. Errant Signal, 2022.

And a video dissection of the TikTok algorithm from the Wall Street Journal: “Investigation: How TikTok’s Algorithm Figures Out Your Deepest Desires.” Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/video/series/inside-tiktoks-highly-secretive-algorithm/investigation-how-tiktok-algorithm-figures-out-your-deepest-desires/6C0C2040-FF25-4827-8528-2BD6612E3796.

Good stuff, thanks for the detailed footnotes (yeah, somebody’s reading them!)

Enjoyed this a lot, Mark. Looking forward to further explorations on the topic!