Technological rubble

"There is rubble, but we build grand (if also temporary) palaces atop it."

Read time: about 12 minutes. This week: Anu Kirk, Vice President of Product at OssoVR, musician, and inventor reflects on technology, history, careers, and work. Next week: Catching up on what the Internet is saying about previous topics that have come up in Technocomplex. A collection of links to extend the stories.

And, of course, your friends are just waiting to see this post.

A few years ago, I was having lunch with a colleague. We were musing about our respective careers and achievements in various industries. He said, “We’re just working on the next layer of technological rubble.”

I laughed and agreed. For many workers, including me, technology magically creates jobs. But that magic is like the monkey’s paw: those jobs will be obsoleted by newer technology, in a never-ending cycle. You cannot get too comfortable, because the same technological progress that paid you last week will leave you behind next week. Your skills will become useless, or even a liability if people read your resume a particular way and decide you and your brain are too old-fashioned for their cool new thing.

Products resulting from the jobs are temporary, too. You can watch your life’s work become useless or unusable overnight. It is perhaps fitting that the foundations of our modern world — microchips — are made of sand, as it sometimes feels like all of the modern world is built on sand — shifting, unreliable, and likely to give way at any moment.

An industry of talent worked on applications for MS-DOS, coding, marketing, selling … until Windows reduced it to rubble. People built games, jobs, and entire companies around Macromedia’s (and then Adobe’s) Flash, until it too became digital rubble. There are graveyards for media formats like reel-to-reel tapes, LaserDiscs, Betamax and VHS, ZIP drives, and CD-ROMs. Or extinct species of videogames that once touted their blocky graphics as incredibly lifelike and realistic. They, too, are now buried in trenches in the desert, with their imagery now resurfacing only as kitschy nostalgia.

At one time, most homes had players for DVDs and CDs, and proudly displayed libraries of favorites. These devices and discs gave way to iPods and paid downloads, which streaming quickly replaced. Streaming washed away factories and workers who made the players and the discs, and teams who warehoused boxes and delivered them to homes. Proprietary and incompatible “smart speakers” have kicked home stereos and boomboxes out of our homes, and funnel data about our listening habits back to their true owners.

But the new world is far easier to operate, and has far more available to you than you had before. No “we’re out of stock.” No fumbling with boxes, and less plastic, packaging, and fuel involved with getting something in your hands. No leaving the discs in your car. No worrying about scratches or bad cables.

And if you just want to hear a song once, you don’t have to throw down $20 for a plastic disc or stay glued to the radio, hoping. Just ask, the machine will play it for you.

The story of churning technology goes back, of course. It is the story of humanity, of man, the tool-maker. John Henry lost to the steam hammer, but the steam hammer lost to something like the Tuen Mun-Chek Lap Kok tunnel boring machine. Appropriately, most tunnel boring machines end up buried in the tunnels they dig, or chopped up and sold for scrap as soon as their task is complete.

Technology offers a step or a massive leap forward in capability. Tunnel boring machines are remarkable achievements of engineering and ingenuity, and drill bigger tunnels better, faster, and safer than anything that came before. Streaming media has put a modern Library of Alexandria (or at least the complete works of Disney, Marvel, and Taylor Swift) at our fingertips. If it existed, you can probably play it for practically free in seconds. Even software is better, with frequent, fast updates easily delivered in the background.

There is rubble, but we build grand (if also temporary) palaces atop it.

Technology’s rapid adoption might scare us, but we are also rapidly adopting it because it is so beneficial and useful. When I lived in Los Angeles in the 1990s, I had a massive Thomas Brothers guide I kept in my car to navigate the streets. Google Maps is superior in every way, and also updates my route in real time to get me to my destination as fast as possible. I could not have even thought to wish for that thirty years ago.

The Computer Swallows Everything

In my few decades of working, technology has transformed everything about jobs. Everyone used to have a phone line, hardly anyone had email. Now the reverse is true.

My first offices had typewriters and telephones at an otherwise empty desk. A time-lapse film would show a massive desktop monitor suddenly appear, then grow and stretch as the typewriter suddenly vanished. The actual computer unit would shrink until it and the monitor morphed into a slim laptop. The desktop telephone would briefly become a network-based voice-over-IP device before disappearing altogether, mooted by the mobile phone which appears to have stabilized as the black mirrors we all carry.

And then in the pandemic, first the person disappears from the desk, and suddenly the entirety of the desk and office disappears as well, leaving behind empty space.

The time-lapse would show a similar thing in recording studios. A computer would suddenly appear off to the side. It slowly would proceed to eat everything in the room, starting with the equalizers and other sound-adjusting boxes, then the tape machines, the mixing board, the drums, the drum machines, synthesizers, bass, guitars, and eventually engulfing the recording studio itself.

Technology even swallows the artists, who no longer need to sing in tune, play in time, or do anything other than look good while a team of technicians click a mouse. And with Photoshop which itself replaced airbrushing of color film images, you don’t even have to look that good.

When I first worked in a big recording studio in the 90s, I had to learn how to align the heads on a 24-track tape recorder, a tedious but important task. That skill, which had been essential for recording engineers since the 1950s, became useless less than 10 years after I acquired it.

This is not really surprising. Business always looks for ways to reduce costs. Some human labor is expensive because the skills involved are hard to find, difficult to develop, and the quality of output can vary from person to person. If business can find a way to take that cost and variability out of the equation, it will.

People are costly, unreliable, inconsistent. Hiring more of them is always a pain. Buying more computers is comparably easy.

This makes even more sense when you realize some jobs require people to do little more than a machine. People typically think of automation as replacing assembly line workers, who were doing repetitive tasks for hours at a stretch, or who couldn’t weld as fast or consistently as a robot.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

More recently and quite visibly, automation has effectively replaced most bank branch employees, between ATMs, websites, and mobile apps. Or consider customer support agents. Modern systems mean people don’t need deep knowledge of what they are working on, they just need to read a script and push a button.

At some point, you can get rid of those human agents, and just have a robot (whether hardware or software) do the script-reading and button-pushing. The robots will be less expensive and more scalable. And robots don’t mind when you yell at them.

We have been used to talking to robot customer support agents for a while. The voices have gotten pretty good, and we have learned to talk to them in ways they understand — even if that means sometimes shouting “OPERATOR! REPRESENTATIVE! HUMAN BEING!” into the phone until some unfortunate person is connected to us.

Automation is making inroads to replace skilled white-collar people like lawyers and therapists. This isn’t necessarily bad. Some legal work, like making a will or setting up an advanced care directive, is effectively an expensive Mad Lib. Some of the most tedious and expensive legal work is going through documents — sometimes thousands of items — in the process of “discovery.” Computers have made the process more accurate and efficient.

If you can get a machine to do it faster and with less expense, that’s probably a good thing – unless you are a lawyer whose business is filling out these expensive documents for people.

If you’re someone who is uncomfortable talking to a person, or if you can’t find a therapist (there’s a huge shortage), perhaps a robot therapist is not so bad. But It is easy to envision some overly-thrifty health insurance companies deciding they will only pay for robotherapy, or trying to build or buy their own system.

Computers are coming for the arts, too. GPT-2 made a few waves in 2019 because the developers said it was so good it was dangerous for them to release the full algorithm. GPT-3 is now available, and GPT-4 is coming. These computer writers are probably not going to displace the likes of James Patterson and Danielle Steel just yet, but they will almost certainly displace a cohort of technical writers and copywriters who closely follow style guides and house rules in an attempt to write less like an individual to begin with. Perhaps some authors will use these tools as a way to get a first draft or parts of a rewrite done. James Patterson frequently hands outlines to a team of writers that crank things out for his novel factory. Why not have a team of bots instead?

The back half of 2022 has seen a flurry of stories around machine learning systems like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion creating visual art. They are surprisingly good, and for typical commercial art, it is easy to see how people might turn to this instead of humans.

I think of all of these people — factory workers, professionals, commercial artists. Their hard-won skills and experience are approaching the event horizon of modern automation. Perhaps some of them will be glad to be set free from jobs they hated or found tedious and soul-crushing. Perhaps no one should have to spend eight hours a day welding metal together in exactly the same way, or listen to angry people yelling over the phone about problems, or try as hard as they can to write in a completely neutral, emotionless, empty non-style.

But they will all need a job doing something else. Perhaps one less tedious, if they are lucky. Perhaps only until the machines catch up to them again. I don’t know what to tell them.

I am one of them, too.

Balancing on Shaky Platforms

I now work for a company that builds virtual reality training simulations for surgeons. Our software currently runs on the Meta Quest 2 headset, and it relies on Unity, a middleware development tool.

While the headsets and middleware are the things that create, empower, and enable our business, they are also some of our biggest liabilities and headaches. The first Quest headset was released in 2019, and represented a significant advancement over the Oculus Rift it replaced. While less powerful than a typical Windows PC + Rift system, the Quest was dramatically less expensive (a tenth of the cost!) and did not require big, bulky cables tethering the headset to a computer. It was self-contained. The Quest 2 followed just a year later, upgrading the graphics and computing power.

Meta is rumored to be launching a new headsets both this year and next year. If those headsets aren’t sufficiently backward-compatible, my company will have to modify hundreds of separate pieces of software to run on the new headsets. We sometimes have to do a bit of this when Meta updates their operating system or software. Those kinds of platform updates can cause problems, even as they offer new features.

The Unity middleware platform is no different. Talk to any developer with Unity experience, and they will talk about how the new version fixed a bunch of terrible bugs, but also introduced a bunch of new terrible bugs.

There have been rumblings Unity might be in trouble. That would be bad for my company and countless other developers who rely on Unity’s software.

I have been designing, building, and shipping technology products for three decades. Challenges like this are inherent in building anything on someone else’s platform. And in 2022, you cannot build any software or hardware that doesn’t rely on someone else’s platform.

Two operating systems dominate the market for personal computers: Microsoft Windows and Apple OSX. Two operating systems dominate the market for mobile phones, which are really just computers, and how most people compute most of the time: Apple IOS and Google Android. Android is also used as the operating system for many other devices, including tablets like Amazon’s Kindle Fire, smart TVs, and even the VR headsets made by Meta and Pico.

VR and AR (sometimes referred to collectively as XR, or “face computers”) represent the final form for computers. In a few decades, computers shrank in size: Once the size of rooms, they now fit into our hands. Simultaneously, computers have gone from no networking to being constantly connected to the internet. Once only owned by corporations and governments, and now everyone has at least one.

Critically, we have gone from never using computers at all to all of us using computers all the time. You are doing it now, as you read this.

Once we put them on our faces and are looking through them constantly while awake, there is nothing else. You can’t do it more than that.

There will likely be two dominant operating systems for face computing. Meta has committed to being one. I have a hard time believing Meta will continue to rely on someone else’s operating system -- they don’t want to be on someone else’s platform. They want to be the platform, and, for better or worse, they are several years ahead of nearly everyone else in the space. They are on track to achieving their goals.

As I strategize about my own company’s future, I am all but certain there will be some platform drama coming. It is inevitable. I also suspect there will be at least one other player we have to support in the near future, adding to the complexity and fragility of our business and others developing virtual reality products.

I will continue to balance on these shaky platforms, hoping they stay stable and afloat long enough for me to figure out what to jump to next. Like Mario in a Nintendo game, I have been jumping from platform to platform for a long time. The only thing worse than a shaky platform is no platform at all. No platform means you fall to your death, a cute sound plays, there’s a bit of animation, and then the game is over.

William Gibson famously said “The future is already here -- it’s just not evenly distributed”. If some group of skills -- and by extension, the people who possess them -- are being made irrelevant by technology today, and if that technology is getting better every day, perhaps we will all become part of the next layer of technological rubble.

Got a comment?

Tags: games, VR, AR, medical education, technology replacement, innovation, employment, job loss, job creation, digital technology development, music, streaming

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

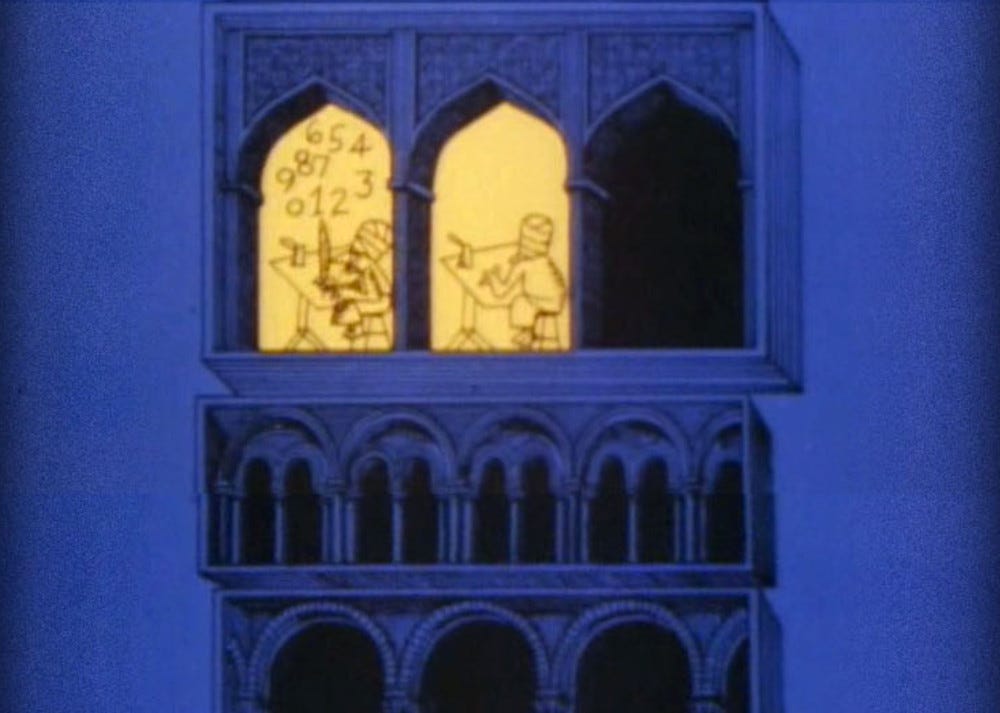

Saul Bass’s short film, sponsored by Kaiser Aluminum, won an Oscar in 1968 for best short documentary. In 2002 the film was added to the US National File Registry by the Library of Congress. It’s worth a look, though it is slightly dated: Why Man Creates. Saul Bass & Associates, 1968.

Includes a “matrix” image derived from the initial section of Why Man Creates. Cleaned up, it’d make a nice poster. Lederer, Henning M. “351 // MA-P / Why Man Creates.” Machinatorium (blog), January 6, 2012. https://machinatorium.wordpress.com/2012/01/06/351-ma-p-why-man-creates/.

AKA VR headsets in the future. Ovide, Shira. “Face Computers Are Coming. Now What?” The New York Times, December 8, 2021, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/08/technology/apple-face-computers.html.

Selected links from “daily missive” posts to seminar members:

Quaglia, Sofia. “Amazon’s New Invention Could Let You ‘Speak’ to the Dead — but Should It?” Inverse, July 29, 2022. https://www.inverse.com/innovation/amazon-alex-ai-dead-relatives-chat-bot.

The VR documentary won an Emmy — the first one from The New Yorker: Reeducated: A New Yorker Documentary in Virtual Reality. VR. The New Yorker, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/news/video-dept/reeducated-film-xinjiang-prisoners-china-virtual-reality.

Parrish, Nick. “The Bike Bus Edition.” Substack newsletter. Why Is This Interesting? (blog), October 4, 2022.

Wills, Matthew. “When the Push Button Was New, People Were Freaked.” JSTOR Daily, May 11, 2021. https://daily.jstor.org/when-the-push-button-was-new-people-were-freaked/.

Anu was a guest in my fall seminar this past week, and he did a great job laying out and exploring many of the things that appear in this post. One student came up to me yesterday and told me how much she enjoyed his visit, and she was amazed by the commitment and the detail he provided in his responses to students' questions. Everyone posed two questions before Anu came to visit (via Zoom); Anu studied them and went well beyond that to respond to every one of them -- 21 pages of responses, in fact! He is a treasure -- multi-faceted, uniquely talented, compassionate.

“It is perhaps fitting that the foundations of our modern world — microchips — are made of sand, as it sometimes feels like all of the modern world is built on sand — shifting, unreliable, and likely to give way at any moment.”

What a beautifully sad description that promises to stick in my brain. Wonderful read, Anu, and great job procuring this piece, Mark!