Three sonnets on a lone majestic oak

It mysteriously avoided the chainsaw and stands in a widened place in the middle of a four-lane highway. I propose a mythology to explain.

Share:

Subscribe (it’s free):

A few miles south of where I live, the normally well-regimented and neatly median-separated highway gently widens and then gently returns to its carefully measured form. Regulations govern the width of medians, not only lanes and road-width, but for a brief moment Highway 501 wanders.

I think the wayward curve pays respect to a magnificent pin oak that someone decided to let alone. The reasons for the violation of road-building rules remain clouded. I once thought that the careful bend to avoid cutting the tree down aimed at preserving a beautiful oak, but that’s, well, too sentimental and improbable. Beauty figures little into highway construction.

The lone oak tree in a widened median must have a more compelling story. A mythology, maybe.

I figured I’d tell a plausible tale. In three sonnets.

I lay out their genesis and development, too.

Other sonnets, also centering on trees:

Here’s where the sonnets stand.

I Hardly dirt, the road. Enough to creep along on iron tires. Or rubber, sometimes better. Tarred Carolina gravel separates her from him. She presses corn-mealed fingers to her cheek, looks at him digging there – over there, across. Digs a hole for the old dog, while the dog’s boy cries and wrings his soiled shirt. The dog just lies, lies, waiting for his hole to open, waiting for his final rest. The tree will mark it. A year or so sprung from an acorn, soon a dog’s headstone but now just spindly oak. Roots not big enough to be greedy or tear the rock below, a sapling crowns the hill, seed once buried and forgotten. Still, far enough from plow and road to grow. Grow old, maybe, old enough to become memory. II Tears. Remember. There, at his son’s feet, shed, as a boy, over his dog at his own daddy’s feet. Greyed fence separates son from father. Road, too, and wider. He presses knarled hand to ear, reaching for their voices, but hears no one talking there – over there, across. Foreman looks to the woods near a tree, scans an easier grade. Tired of complaints and sweat, he fears uncovered bones. “My dad, there. His daddy’s prize horse lies here. Spare his grief.” The tree marks it, now grown to match a taller tale: boy’s dog transformed to granddad’s ribboned horse. Foreman calculates disturbing bones – maybe not a beast’s – and eyes an easier path to grade. Hardly a markable change. Still far enough from plow and road to grow. Grow old, maybe, old enough to become memory. III They pulled wood-pegged gears from the mill’s wreckage so that they could ornament a micro-brewery restaurant. "No payment needed. Take it. Just trash, ancient trash." I press the air conditioning button cooler, raise the music, see their wood-gear-laden truck pull out. Over there, across, poppies planted near the tree show off. The old oak, like an aged champion, raises limbs in triumph. A lie spared its dog tombstone trunk from chainsaw’s bite. Highway ribbons spread wider there, for some reason. Spread to give wide berth to a common pin oak, now poppy-wreathed, blood red above a forgotten grave. Old oak crowns the hill – story-sustained, now secure. Still, far enough from plow and road to grow. Grown old, already, almost old enough to become memory.

How it came together

The tree is real enough. Why it still stands is the mystery. Its precise location is 36°09'45"N 78°54'19"W.

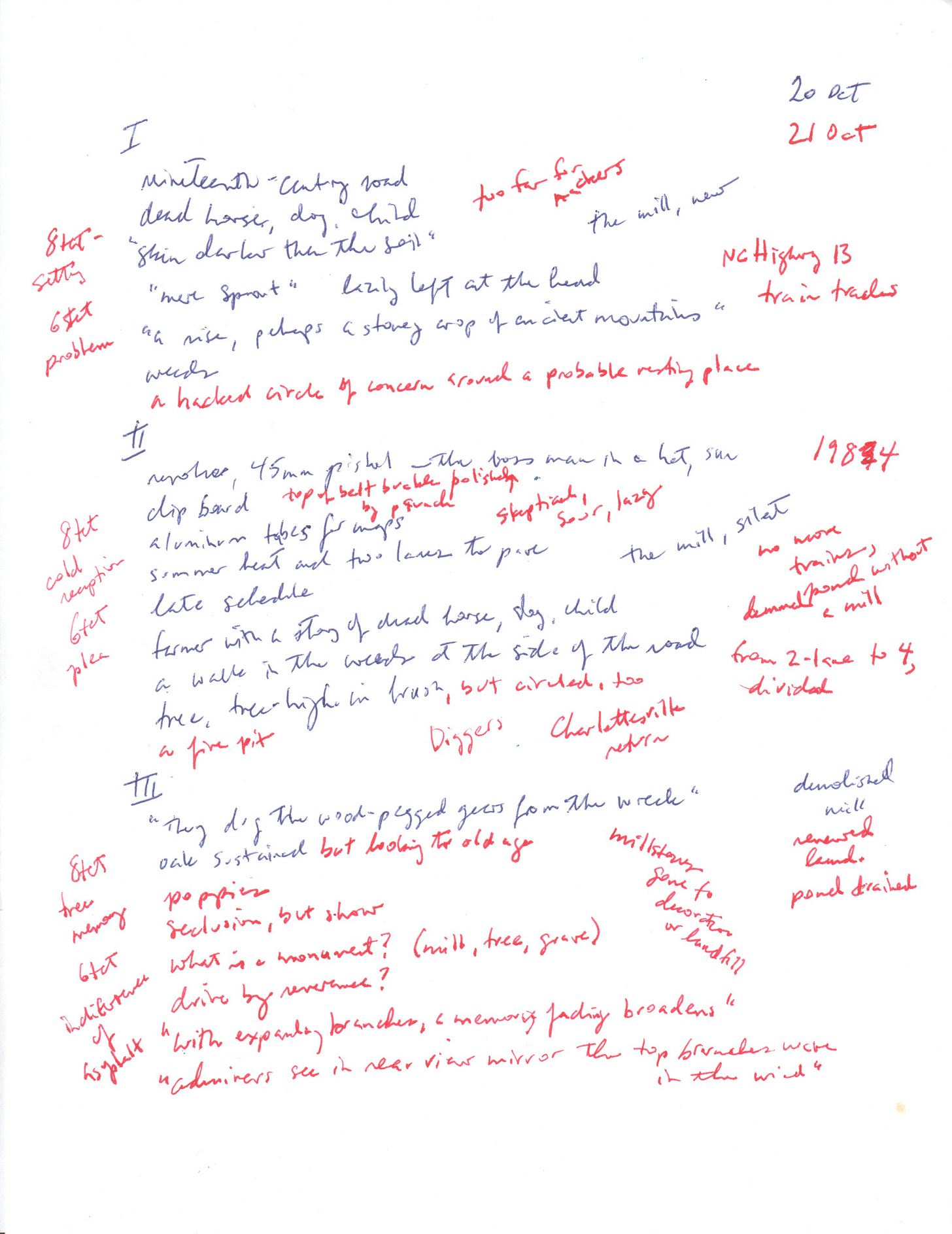

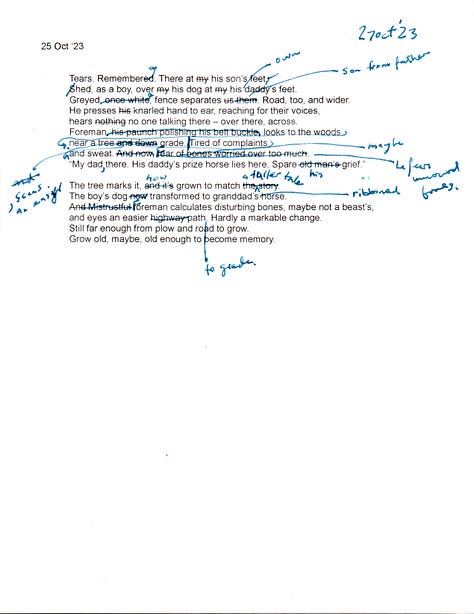

From the first, I intended to write three sonnets: An origin story, a transformation story, and a present story — together covering about seventy to a hundred years. Long enough for an oak to grow to maturity. I pulled together ideas rather roughly, and details far exceeded what I could use in the individual sonnets, though I do think a larger narrative could incorporate them. When I had some bit of clarity, I assigned broad guides for the octets and sestets (noted in the right margin in the photo below).

Because of the time-frame, the first sonnet is nearly all the product of imagination, though I did consult some old maps and online notes about North Carolina Highway 13, which ran near the current Highway 501 in the early years of the last century. Though it was a “state road” connecting North Carolina and Virginia, it wasn’t a superhighway. At the most, it was paved with “macadam,” a mixture of gravel and some binding agent like tar or concrete. My guess it was loose gravel, tended every once in a while.

The second and third sonnets embellish my experience. Bond Girl Bride and I travelled back to Durham in the 1980s after visiting friends in Charlottesville, Virginia, while Highway 501 was getting widened to four lanes — two northbound, two southbound. The third sonnet gathers experiences from the many trips I’ve taken from our home into “town.” There really were wood-pegged gears extracted from the ruins of an old mill located just north of the old pin oak. Its buildings and its dam have been carried off; only the depression of the dammed pond is still visible.

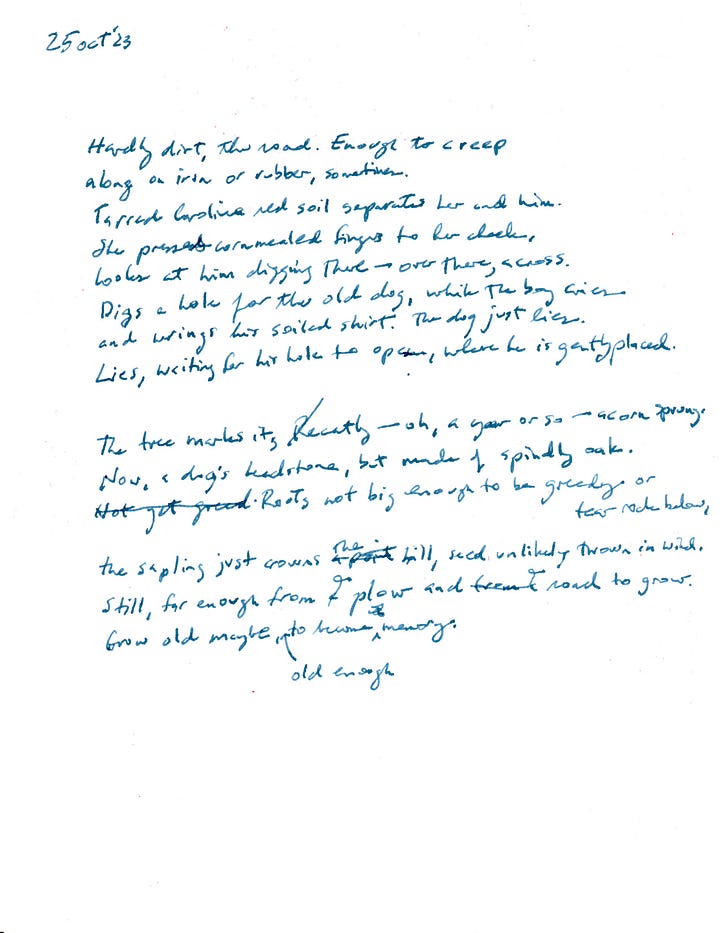

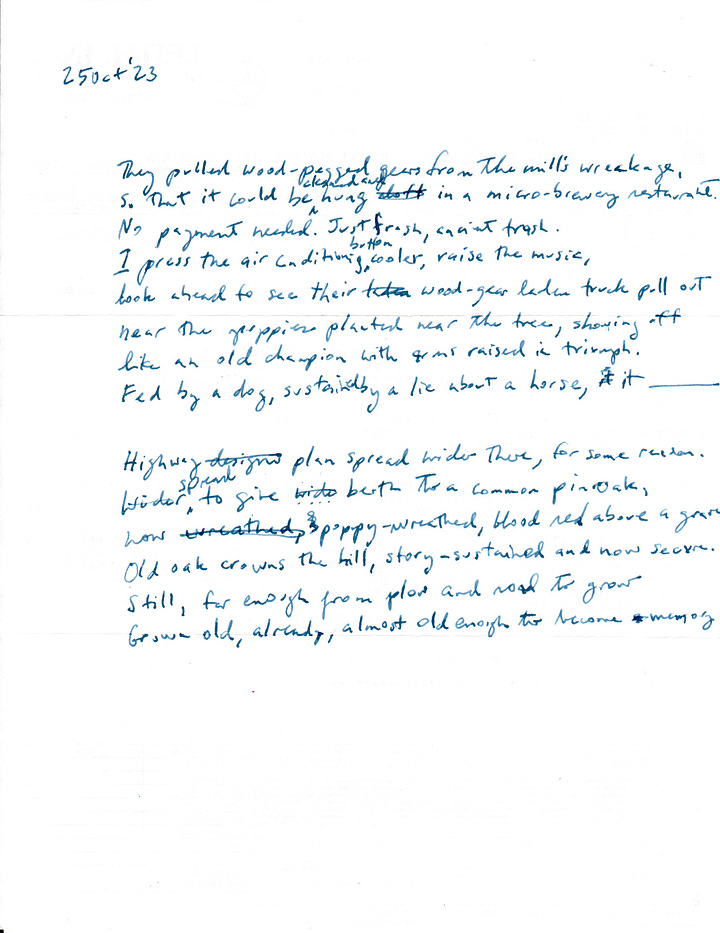

The notes and first drafts:

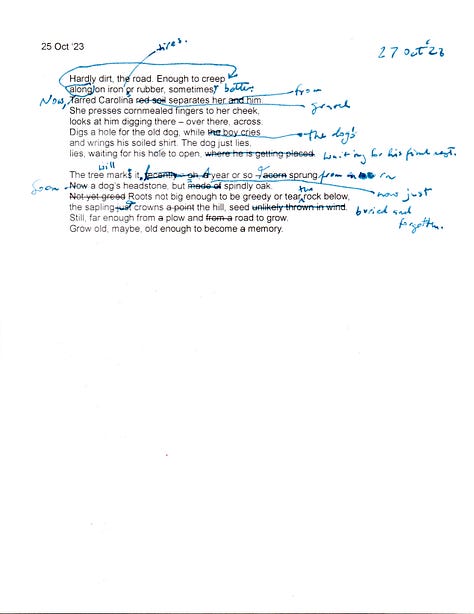

As is my practice, I cleaned up the drafts, this time by entering them into a word processing document. Then I revised.

I returned to the revised sonnets on October 27, and made revisions that are the “final form” (until, of course, I have at them again).

The pace of revision

Readers will notice that I gave myself time to ponder revisions. Rather than setting drafts aside for a day as usual, I gave myself more time. That additional time to ponder and play, I think, allowed me to create a scheme and a plan for the whole series. I found that much of my thinking about the sonnets and their next revision came to me in the middle of the night. I plotted and planned between midnight and two in the morning.

Not rushing the process made sense, and, while I’m not entirely convinced these sonnets will stay the same in the future, they’re decent drafts.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Tags: sonnet, pin oak, tree, highway, mythology, memory, revision, poetry

Thank you for sharing these and your process. The sonnets are beautifully reflective and a little gut-wrenching, too. I enjoyed each but it’s the synergy of the trio that makes them especially effective.

Beautiful in design and execution, and a worthwhile subject. Thank you for sharing.