Uh ... "Dasein"?

Heidegger was not meant to be read. At least in a common way. An exploration of language and its experience.

You should subscribe so you don’t miss anything!

Martin Heidegger would hate what I did. He would look at me with steely eyes, maybe sigh and sneer. “You’re completely, hopelessly….” he’d stammer. “You’ve turned the essay into bits and bytes. No! You’ve turned your reading of my essay into mere fodder for Standing Reserve!”

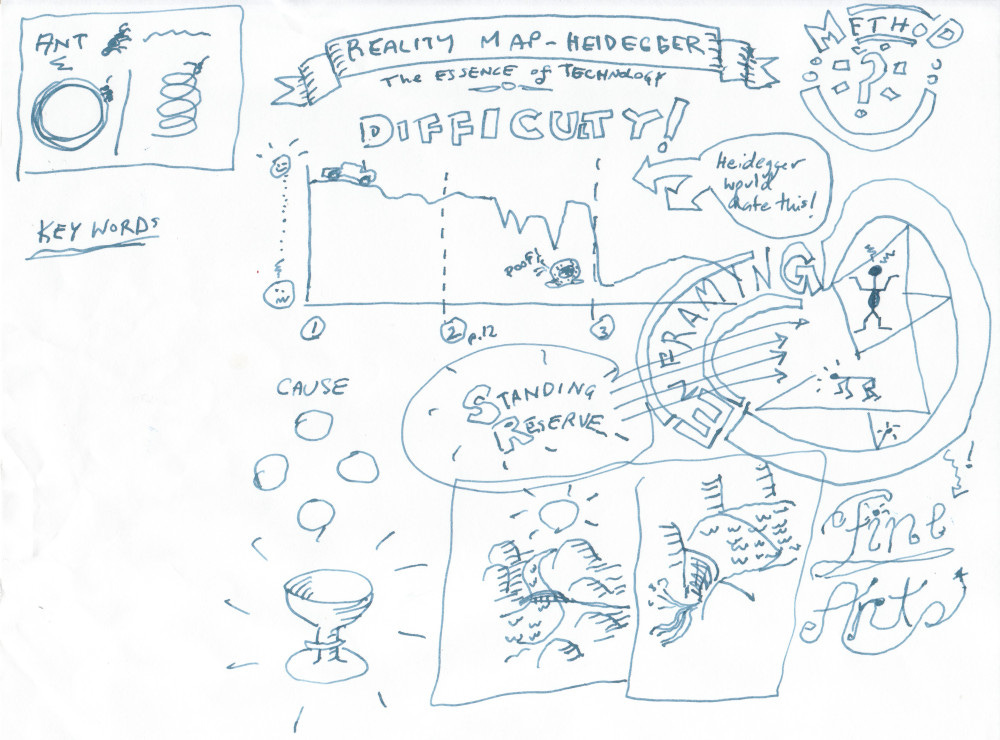

And I guess he’d be right. I did indeed quantify and capture my internal judgment of the difficulty of his essay. I wanted to represent these data graphically. I still have the seven pages of filled out forms that assigned a number, one for each page of his essay, depending on my reading experience on a hot August day in 2021.

Prettied up, here’s the graph. Emojis — Heidegger would probably hate them, too — summarize my perception of the essay’s difficulty. At top: sunny times reading in fashionable shades (100, fully clear and understood); midway down: puzzlement, but an even understanding (50, half-n-half, threats of murk and fog); rock bottom: despair, being is nothingness (0, woe! all is forgotten hieroglyphics). Colored vertical bands signify three sections of Heidegger’s famous essay “The Question Concerning Technology.”

I shared a much less pretty version of the graph with students in my fall 2021 seminar (a lecture note rendering in an illustration below), all of whom were healthily befuddled by Heidegger’s essay, all of whom struggled through re-readings and puzzlement with their peers in dorm rooms, and some of whom actually came to appreciate some aspects of Heidegger’s views. (I don’t think anyone was enlightened, at least by Heidegger.)

I wanted to let students know that reading is sometimes a struggle. Always a struggle sometimes, no matter where you are in life. It depends on what you choose to read, what you’ve read before, and what you want out of reading — or, perhaps, what your reading can reveal with you.

That’s especially the case with Heidegger’s often inscrutable words, which some of his philosophical contemporaries vigorously pointed out and trashed. Metaphysics, which Heidegger offered in his work, incited fury or at least head-shaking disbelief from members of a rising “analytic” school. A leading light among them was Rudolf Carnap, part of the “Vienna Circle” group that focused particularly on how statements are meaningful or, contrarily, not to put too fine a point on it … bullshit. “Carnap thought that most of what philosophers do when they write about metaphysics is compose semantically empty sentences, which he calls pseudostatements,” Sam Dresser wrote in a fine essay in Aeon. “Sentences of this metaphysical flavour appear to say something profound, since they are grammatically correct. But careful investigation reveals that, not only is nothing profound being said, nothing is being said at all.”

Heidegger was the poster boy of pseudostatements, as far as Carnap and the Vienna Circle were concerned.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

Today, the influence of the Vienna Circle is still felt in the way that philosophers do their work, even though the intellectual core of the movement — captured in the principle of verification — failed to pass the test for certainty that it proposed. That is, principle of verification itself couldn’t be verified as certain. (Dresser’s essay contrasts Heidegger’s use of language with Carnap’s, and provides a sympathic view of both, as philosophically distant as they are from each other. Like I said, it’s a good read.)

Well, if it’s meaningless, what hope do I have to understand it?

Harsh criticism of Heidegger’s work in Carnap’s “The Elimination of Metaphysics through the Logical Analysis of Language” took some of Heidegger’s difficult statements (they are not hard to find) and subjected them to Carnap’s rigorous method. He determined they were meaningless. But they were meaningless according to Carnap’s rather constrained view of language and the statements that are appropriate to philosophy.

Heidegger’s view of language and his view of the prospect of philosophy was quite different from Carnap’s. In short, Heidegger said that Carnap mistook the difference between certainty and truth, for while Carnap’s rigor could test the certainty of statements, it could not signal the truth of statements. In Heidegger’s view, poetry — as uncertain as it is by design — can also signal truth, and language can be used as a tool to reveal truths that lie beyond the constraints of the kind of rigorous logic that Carnap proposed.

That’s one reason that art plays a key role in “The Question Concerning Technology.” Heidegger is interested in larger frames of experience than Carnap and the Vienna Circle would see as appropriate to philosophical thought. Heidegger’s language, in effect, bends us to peer beyond fences that the Vienna Circle erected to preserve certainty.

If you can see the contrast of views of language from Heidegger and Carnap, you can probably also see why reading Heidegger is hard. (And, probably also why reading Carnap is, well, boring.)

You can also understand why Heidegger would use new words, some crafted from words in common use but gathered, juxtaposed with inserted hyphens, some reintroduced to harken to an earlier, even ancient, meaning. He even saw some languages as privileged in matters of philosophy — ancient Greek and German. (His reasons, however, are suspect and even condemnable.) From a more distant perspective than a focus on words, “The Question Concerning Technology” has an overall structure that spirals; it poses questions, elaborates, finds a settling resolution from which a new question emerges and flies, ever upward (or downward, I guess) into the depths of an argument. Its last words are “For questioning is the piety of thought,” which I think is a beautiful summary of the Heideggerian project.

You could say that Heidegger is hard to read because the words never seem quite sufficient to contain the meanings that he might be trying to offer — so it’s fair to say that Carnap is right to be suspicious. Heidegger’s prose is hard in new ways, too: we’ve all read papers where we run into technical terms and jargon, but those usually have quite precise and certain meanings. Heidegger’s do not, by design, I think.

Dresser puts the effect of Heidegger’s work this way, and I think it applies to the basic encounter of his words and sentences: Heidegger seeks “to dislodge his listeners from their complacent philosophical attitudes, to question assumptions so extraordinarily basic that they often go unexamined. He wanted to point to what is too close to be seen. His style of thinking has been called ‘event philosophy.’ ” The “event” being the snap of insight that may be fleeting but that also can transform.

A method in this madness

It’s easy to say that reading work that bends language is hard. It’s harder to devise a scheme to surmount the difficulties of the task of reading, and maybe just as hard to expect to benefit from the experience. But there are ways. Let me try to enumerate them:

Read to scope out the landscape of a piece, and don’t toil on individual words or segments.

Grab a commentary, ideally a video that seeks to explicate or elaborate. Sometimes a shift of medium (like a video) helps to establish a new view of the work. Be aware, however, that commentary can be bunk and that it’s always insufficient.

Re-read the piece, paying closer attention to the structure. Circle words that appear to be important. (For books, take a look at the index, since indexed words are usually important.) Try to find ideas that may serve as hooks holding on to thoughts and ideas that are more familiar to you. (A footnote is often good for this kind of information.)

Let it sit. Your mind will work without you pushing it.

Repeat as you wish, but more than once.

I’ve had students who have found that reading with someone else has been useful. Often they’re mutually befuddled, they’ve said, but the have been able to share points and bolster each other’s reading. This makes sense to me, because in effect the few steps I’ve listed amount to a more-or-less systematic way of engaging the hard text in dialogue. Reading companions help with that dialogue.

As this Substack post goes out, students are prepared for the seminar discussion. It happens midday today, and I expect it’ll be at times difficult, at times humorous and, I hope, end with a greater appreciation for the work. And, maybe, some greater understanding of technology.

Got a comment?

Tags: Martin Heidegger, prose, reading, philosophy, Rudolf Carnap, Vienna Circle, logical positivism, metaphysics, technology

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

It’s the first essay. Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. Works. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1996.

A very readable and interesting essay on Carnap and Heidegger and the promise that an open end, an ellipsis, can make in life: Dresser, Sam. “Heidegger v Carnap: How Logic Took Issue with Metaphysics” Aeon, June 23, 2020. https://aeon.co/essays/heidegger-v-carnap-how-logic-took-issue-with-metaphysics.

Two essays from Charlie Huenemann that relate to the topic of reading and language: Huenemann, Charlie. “How to Read Philosophy.” Psyche, August 31, 2022. https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-read-philosophy-with-an-adversarial-approach and “Who Needs a Perfect Language? It’s Already Perfectly Imperfect.” Aeon, May 30, 2017. https://aeon.co/ideas/who-needs-a-perfect-language-its-already-perfectly-imperfect.

A paper from Yale researchers that says readers live longer. I wonder if that also applies to readers who torture themselves with Heidegger essays? Bavishi, Avni, Martin D. Slade, and Becca R. Levy. “A Chapter a Day: Association of Book Reading with Longevity.” Social Science & Medicine 164 (September 1, 2016): 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.014.

Of course, you could just get Martin Heidegger socks and call it a day: https://www.etsy.com/listing/550373984/martin-heidegger-socks

And from daily missives I’ve sent to the class over the past few days, here’s a few links. (I thought former students who get this newsletter might like these.) They might seem contextless in this post, but you can probably see traces of class topics.

Gitlin, Jonathan M. “No, BMW Is Not Making Heated Seats a Subscription for US Cars.” Ars Technica, July 12, 2022. https://arstechnica.com/cars/2022/07/no-bmw-is-not-making-heated-seats-a-subscription-for-us-cars/.

Forelle, M. C. “Copyright and the Modern Car: Colliding Visions of the Public Good in DMCA Section 1201 Anti-Circumvention Proceedings.” New Media & Society, May 17, 2021, 146144482110152. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211015235.

Jana, Rosalind. “The Joy of Mending Things.” BBC Culture, August 22, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220822-why-we-are-drawn-to-mending-things.

Alexander, Scott. “My Bet: AI Size Solves Flubs.” Substack newsletter. Astral Codex Ten (blog), June 6, 2022.

Marcus, Gary. “Does AI Really Need a Paradigm Shift?” Substack newsletter. The Road to AI We Can Trust (blog), June 11, 2022.

Wow, what a cool way of thinking about reading difficult stuff--far better than the kind of snobby elitism that implies that if one doesn’t understand the difficult text, perhaps one isn’t “good enough” to be in the club. It reminds me of the “encounters” with deconstruction (Derrida, Saussure ... or was it de Saussure) I had in grad school decades ago. One prof looked down his nose at those who found it challenging and said, “Well, you must go back and read it again,” while another took it as pure play and delight to grapple with the difficulty (as you have done here). You can bet whose seminars were packed.