"Time to BeReal"?

Photography reveals relationships of technology and humanity. Are we part of an imaging "apparatus"? How do we use it to create?

Read time: about 8 minutes. This week: The play of art and technology. BeReal and nifty “phototourism” from Google. Next week: Virtual reality and the reality of imagined worlds.

Share, please:

One of the things that happens in a time like ours is that some assumptions we commonly make are challenged. Not exactly uprooted or denied or contradicted, but more rendered ambiguous. Landmarks seem to shift and boundaries seem unfamiliarly placed. This has happened in many ways and in many areas of our experience over the past decades and has accelerated as common life shrank under pressure of the pandemic. Or maybe changes have become more apparent as they have pressed more deeply into our understandings of ourselves, our societies, and our place in the world. Some are monumental and difficult to fathom — climate change, for example — others are more localized and acutely press on our communities — demographic, economic, media-industry, and political changes in the United States, for example.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

Lately, I've focused on sets of boundaries drawn in part to define humanness with art and creativity and to help us individually see our actions as our own — as our humanity expressed. Such lines have become ever more fuzzy, because of the challenges and achievements of artificial intelligence and the networked binding of social media. AI, some say, creates art — and art forms a foundation, a monumental landmark of what it means to be human. AI may be a challenge.

How is art human? Is it possible for art to arise, say, from clever algorithms and ample electrified silicon? Can computers be creative? — a question that some label as “misguided.” Earlier this year, in the first entry of my ’stack, I wrote about the ways that early “documentary photography” gradually developed norms and contours of an art form and have shifted and morphed continuously. The piece began by looking at two photographs taken by Roger Fenton during the Crimean War.

Differing only by time-of-day and locations of cannonballs on (or off) a desolate road, Fenton’s photographs have been thoroughly discussed and argued about, usually in an attempt to identify which of the pictures (if any) is “fraudulent.”

Of course, photography has developed since the nineteenth century. Vastly developed, especially in the past decade. And it’s not just in terms of image capturing, but the scale of what might be called the project of photography. It’s often easier to find a camera than not. In any given area on a college campus, for example, you can count at least as many picture-taking devices as people milling around.

Roger Fenton had to lug heavy equipment, or as the case may be, have his equipment lugged for him. His decision about cannonballs or not had its own justification, and they were his own, independent of professional standards for documentary photography — in his day still amorphous. Today’s ubiquity of cameras gives rise to other questions, perhaps the most obvious being where and when it’s okay to snap and share. Beyond just being everywhere, image capturing devices have becomes parts of larger “multi-purpose” configurations, becoming and automatically using features like GPS location, networked uploads, automated “enhancements” and even facial recognition. These unobtrusive (and handy) additions change the meaning of “taking a picture” and open up new photographic opportunities. In short, convergence of features and collations — like Flickr or Wikimedia Commons — lay the groundwork for newly created images conjured up with computational methods. Products from individual devices add up; devices become part of a larger entity, a new “apparatus.” Your smartphone surely ain’t your great-grandfather’s Kodak Brownie. Or even your dad’s Nikon 35 mm SLR.

Ubertourist photography

A Google team summed up their project in the first sentence of the abstract of their publication: “We present a learning-based method for synthesizing novel views of complex scenes using only unstructured collections of in-the-wild photographs.” In other words, they created new views of tourist landmarks with tourists’ abundant and haphazardly grouped images. To show off their work, they “recontruct[ed] the Trevi Fountain and Sacre Coeur as well as four novel scenes, the Brandenburg Gate, Taj Mahal, Prague Old Town Square, and Hagia Sophia.”

“NeRF in the Wild: Neural Radiance Fields for Unconstrained Photo Collections,” fully describes the method that the team used to make “novel views” of the landmarks. I won’t belabor the process they went through (you can read the article for the details); a Youtube video shows the results:

NeRF-W reconstructions appear like motion pictures we already know well, and many of us have experienced making old school film-photography movies. But, unlike shooting the home movies of old, the reconstructions from the Google project derive from hundreds, if not thousands, of individual digital images taken on different days at different times with cameras of differing image capture capability, and snapped by different people. No controlled lighting conditions or consistently beautiful weather. Given its origin in inconsistent snapshots, the NeRF-W demonstration video is difficult to categorize: Though a product of photographic imagery, the NeRF-W depiction of the Trevi Fountain and other landmarks never directly fell through a physical glass lens. Rather, the contraption that “made the movie” whirred in an air-conditioned room, had no image capturing instruments, and could function as well in the dark as in light. It could run anywhere on the planet with ample electricity. Likely as not, its machines were tended by hardware technicians whose only cameras were on the Google Pixel phones in their back pockets.

It’s a long way from Fenton’s cannonballs/no-cannonballs photographic creations to NeRF-W computational “phototourism.” Still, the Fenton’s old technology exerted pressures on artistic definitions as do the recent Googly reconstructions.

BeReal. One big photographic apparatus?

The Google team’s ingenuity computationally conducted a rag-tag, asynchronous army of amateur photographers to come up with a performance of a coherent symphony of images. Their task included massive organization of piles of unorganized images of the same landmark sites. An up-and-coming newcomer on social media has built a massive organization of image takers, in effect extracting images from an army regimented by time-of-day and living in different scenes.

Some of those images might even be at landmarks, but that’s not the point.

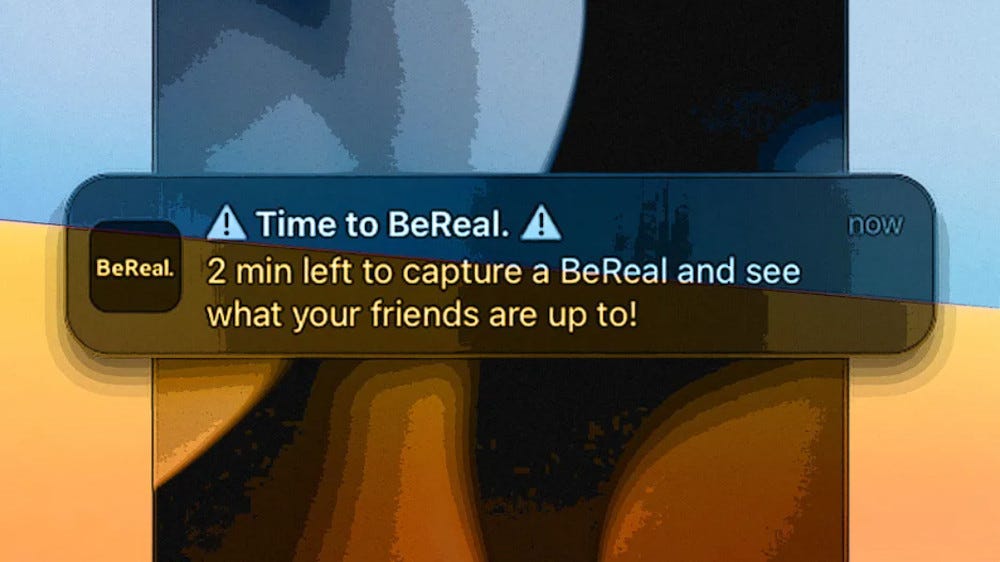

The social media app is called BeReal, and it organizes its users, who take pictures wherever they are when the BeReal app issues its command: “Time to BeReal.” BeReal users have two minutes after that to snap a picture with their smartphone; both front- and rear-facing cameras engage simultaneously. Friends see the images. No time to fix your hair. No time for selecting poses. Just you being real. French newspaper Le Monde called BeReal l’Instagram de la vie moche — “Instagram of the ugly life,” which of course sounds better in French.

There’s a catch, too, that adds a bit of pressure to post. “BeReal prevents users from lurking: To see anyone’s images, users have to first share their own,” Wall Street Journal reporters Dalvin Brown and Cordilia James wrote. “If a user posts late, they don’t have as much time to view others’ photos; all posts reset when the next notification goes out. The aim is to share real life, when it’s happening, with friends.” They noted that Gen Z is fascinated: “BeReal has a different pitch: Post quickly, scroll and go live your life. For some Gen Z users, that is a magnetic idea.”

TikTok and Instagram hope that the magnetic attraction isn’t that strong, but they are countering with BeReal-like features just in case.

I couldn’t help but think of Vilém Flusser’s description of photography when I learned of the BeReal app’s large-scale organization of image-taking and sharing. In Towards a Philosophy of Photography, he offered a unique description of photography according to his “basic concepts” of image, apparatus, program, and information. “This results in a broader definition of a photograph,” he wrote. “It is an image created and distributed automatically by programmed apparatuses in the course of a game necessarily based on chance, an image of a magic state of things whose symbols inform its receivers how to act in an improbable fashion.” And he wryly notes that his “definition has the peculiar advantage for philosophy of not being acceptable” — that is, it invites argument.

In many ways, BeReal and NeRF-W reflect Flusser’s (rather complicated) definition. I would say that BeReal is even more true to Flusser’s definition than the Google project. The alignment of the processes of BeReal and Flusser’s “definition of a photograph” have made me think more broadly about what photographic apparatuses actually are. And how those apparatuses control, limit, enrich, and extend human creativity and art.

Got a comment? Are you using BeReal? What are your thoughts about it. How does it differ from Instagram, say, and what boo-boos might make you give up on BeReal, if the company changes things?

Tags: authenticity, BeReal, Roger Fenton, NeRF-W, 3D imaging, composite photography, Vilém Flusser

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

The NeRF-W arXiv article with the gory details, readably reported, along with somewhat nerdy formulae: Martin-Brualla, Ricardo, Noha Radwan, Mehdi S. M. Sajjadi, Jonathan T. Barron, Alexey Dosovitskiy, and Daniel Duckworth. “NeRF in the Wild: Neural Radiance Fields for Unconstrained Photo Collections.” arXiv, January 6, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2008.02268.

Even ugly is pretty in French: Faure, Guillemette. “BeReal, l’Instagram de la vie moche.” Le Monde. September 16, 2021, Online edition, sec. Le Mag, Chronique. https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2021/09/16/bereal-l-instagram-de-la-vie-moche-au-quotidien_6094926_4500055.html.

Brown, Dalvin, and Cordilia James. “Why BeReal, a Social-Media App With No Photo Filters, Is Attracting Gen Z.” Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2022. https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-bereal-a-social-media-app-with-no-photo-filters-is-attracting-gen-z-11650456491.

Flusser, Vilém. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion Books, 2000.

Useful article on photography and a nice explication of Flusser’s definition of photography: Woodall, Richard. “Telematic Society.” Real Life, July 18, 2022. https://reallifemag.com/telematic-society/. Unfortunately, Real Life ceased publication earlier this month, though the website still exists.

And selected links from recent “daily missives” to members of the seminar:

“A Modern Architecture Home with Exposed Wood and Curved Bamboo, Designed for the Hawaii Climate and Landscape - Architecture Inspiration - Generated by AI.” Accessed September 19, 2022. https://thishousedoesnotexist.org/a-modern-architecture-home-with-exposed-wood-and-curved-bamboo-designed-for/6434202.

“What Happens When Artificial Intelligence Creates Images to Match the Lyrics of Iconic Songs: David Bowie’s ‘Starman,’ Led Zeppelin’s ‘Stairway to Heaven’, ELO’s ‘Mr. Blue Sky’ & More.” Open Culture. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.openculture.com/2022/09/what-happens-when-artificial-intelligence-creates-images-to-match-the-lyrics-of-iconic-songs-david-bowies-starman-led-zeppelins-stairway-to-heaven-elos-mr-blue-sky-more.html.

Dzieza, Josh. “Can AI Write Good Novels?” The Verge, July 20, 2022. https://www.theverge.com/c/23194235/ai-fiction-writing-amazon-kindle-sudowrite-jasper.

Kalinowski, Joseph. “AI Text-to-Image Generators: Job Killers or Friendly Robot Assistants?” Content Marketing Institute (blog), September 8, 2022. https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/articles/ai-text-to-image-generators-job-killers-or-friendly-robot-assistants/.

Rosenberg, Louis. “I Used Generative AI to Create Pictures of Painting Robots, but I’m Not the Artist — Humanity Is.” Big Think (blog), September 9, 2022. https://bigthink.com/high-culture/generative-ai-pictures-humanity-artist/.

Salkowitz, Rob. “Midjourney Founder David Holz On The Impact Of AI On Art, Imagination And The Creative Economy.” Forbes, September 16, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robsalkowitz/2022/09/16/midjourney-founder-david-holz-on-the-impact-of-ai-on-art-imagination-and-the-creative-economy/.

Veltman, Chloe. “New Selena Album ‘Moonchild Mixes’ Sparks Voice-Aging Debate.” NPR, August 26, 2022, sec. Music News. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/26/1119162998/selena-quintanilla-moonchild-mixes-album-2022.

Bluestein, Adam. “Why Amazon’s ‘Dead Grandma’ Alexa Is Just the Beginning for Voice Cloning.” Fast Company, August 8, 2022. https://www.fastcompany.com/90775427/amazon-grandma-alexa-evolution-text-to-speech.

interesting, Mark, with the links giving me plenty of fodder for follow-up reading. Did you happen to look at the app called Minutiae? It preceded Be Real by a bit I believe.