Book review: Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture

Kyle Chayka's new book comes out next week. It's a goodie.

Chayka, Kyle. Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture. New York: Doubleday, 2024. 304 Pages. ISBN: 978-0-38554-828-1 $28.00

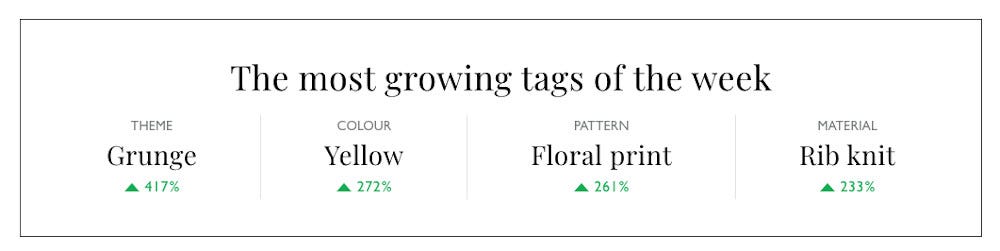

Having nearly wrapped up my review of Kyla Chayka’s Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture (Bookshop.org, Amazon), which comes out next week, I opened up The New Yorker that sat on the kitchen table. Lauren Collins had a piece in “The Talk of the Town,” where the editors gather short and usually entertaining pieces. “Tagwalk Takes on the Hemline Index,”1 which she filed from Paris, breezily reported about Alexandra Van Houtte’s work on a new book and updated news about her online creation that aims to be the “Google for fashion.” Her version of Google, which she set up in 2015, is called Tagwalk (https://www.tag-walk.com/en/), “a free fashion search engine which allows you to search for models, trends, accessories and fashion shows by keywords.”

Since I am a sucker for fashion, I visited the site and learned that, according to the previous week’s web activity, Balenciaga was down one, Versace and Valentino were both up one, and Chanel and Christian Dior were holding steady.

The “grunge” theme tag over the past week was up a whopping 417%, with “yellow” (up 272%), “floral print” pattern (up 261%), and “rib knit” material (up 233%).

I do have to admit that the trending color, pattern, and material seemed a little odd when wedged into a “grunge” theme. I guess we’ll see what happens on the catwalk.

I smiled and thought that Tagwalk could do a good ironing job on clothes — an algorithmic flattening of a cultural niche.

Filterworld

Chayka uses the word “Filterworld” to denote a kind of lens into cultural experience, which is to say an experience of life. The term, he explains, “is my word for the vast, interlocking, and yet diffuse network of algorithms that influence our lives today, which has had a particularly dramatic impact on culture and the ways it is distributed and consumed.”2 He continues:

The culture propelled by Filterworld tends to be accessible, replicable, participatory, and ambient…. It is also pleasant or average enough that it can be ignored and unobtrusively fade into the background, oftentimes going unnoticed until you look for it. After you notice it, however, you tend to see it everywhere.

I saw it in Tagwalk after reading the book.

The itch that Chayka scratched in Filterworld probably started when he was writing his first book, The Longing for Less (Bloomsbury, 2020; Bookshop.org, Amazon), and as I read Filterworld, I felt the kinship. It wasn’t just that the author was the same, though Chayka's clear prose and refreshing style is a constant through both of these books. Chayka’s The Longing for Less presents minimalism as an adventurous, philosophically rich, and productive step in art and culture but also as a lost way taken into the sameness of branding and stylistic cliché. Filterworld focuses more tightly on mechanisms underlying modern culture — algorithmic mechanisms, as the book’s subtitle points out, that flatten culture much as the clichés of Mary Kondo-ish processes had simplified and misrepresented minimalism.

I recalled the word flattening coming up in The Longing for Less where Chayka considers Marc Augé’s and Rem Koolhaas focus on the sameness of airports, with their standardized function and, for Augé and for Koolhaas, a convergence of design and “ambience” that erased distinctiveness and difference. For Augé, airports turned into “non-places”3 for Koolhaas, cities became as “generic” as their airports.

CULTURE HAS “CROSSED OVER TO CYBERSPACE,” AND IN FILTERWORLD CHAYKA SHOWS US THE PATHWAYS IT HAS TAKEN IN THE CROSSING.

Chayka observes in The Longing for Less that “Koolhaas saw the airport as a symbol of a world that was increasingly homogenous: Just like every terminal resembled every other, global cities were also becoming the same” — even “one-of-a-kind cities like Paris.” Koolhaas called the generic city “equally exciting — or unexciting — everywhere” and Chayka points out where this ambient sameness comes from: “This flattening occurred because of technology,” he wrote, and then, again citing Koolhaas: “The Generic City is what is left after large sections of urban life crossed over to cyberspace.”

Filterworld elaborates on themes that Chayka explores in The Longing for Less, probing and untangling the “flattening” not only of the “generic city” but of culture. Culture has “crossed over to cyberspace,” and in Filterworld Chayka shows us the pathways it has taken in the crossing.

The algorithm in your app and in that coffee shop over there

One of the limitations that discussions of algorithms have is a tendency to restrict them to “tech” — to the digital realm, often narrowed to the smartphone. Although it’s certainly true that our typical understanding of algorithms relies on numbers and computation, the algorithm isn’t necessarily tied with silicon or even mathematics. It can be a clear description of a process absent any apparent math, as Cathy O’Neill showed in her discussion of her “model” of family meal planning. She used processes that we can call algorithmic, though in a manner that recalls the word’s much, much earlier meaning.

Given our habit of restricting to “tech,” we also carelessly restrict the influence of algorithms. We tend to think of algorithms as unseen engines for results, which of course they are most apparently in our lives: TikTok presents entertainment, Spotify queues music, and everyone (practically) shovels ads in our direction — such are the obvious results of algorithms that we see.

But Chayka’s book is interested in implications, motivations, downstream consequences of algorithms. And so it’s worth starting a journey through Filterworld apart from the typical algorithms in your phone apps.

We can ask an outrageous question: In addition to the shape of our online experience, do algorithms also shape the physical spaces we occupy and navigate?

Chayka examines “non-places” and “generic cities” in Filterworld’s third chapter, “Algorithmic Globalization,” which begins with “seeking the generic coffee shop.” He explains that

Filterworld is not limited to digital experiences on our phones or television screens. It is a pervasive force that shapes the physical world, too. Because algorithmic systems influence the kinds of culture we consume as individuals, molding our personal tastes, they also influence what kinds of places and spaces we gravitate toward.

In short, “apps direct our attention toward physical places that … meet the platform’s incentives.” Ever use Google Maps? Yelp? Airbnb? — “they create something like an algorithmic Netflix home page but for physical space.”

In the 2010s, Chayka used the apps, and he admits that in cities he travelled through, his search for coffee often started with thumb-typing “hipster coffee shop” into Yelp’s search bar. Since Yelp had him pegged and knew his preferences and probably more of his attributes and foibles than even he probably would care to admit, the app could direct him to a coffee shop of his liking. Google Maps could do the same, of course.

Actually, Yelp or Google Maps directed him to more or less the same coffee shop, no matter where it was located — Tokyo to Berlin to New York to Berkeley. For example, he found the Nitro Bar in Newport, Rhode Island, among other coffee shops, because “[t]he algorithmic recommendations had approximated my taste based on my previous data, automated it, and then served it back to me. They provided a physical shortcut, rerouting my path toward the Nitro Bar.”

Direction or discovery is one thing, of course, but influencing coffee shop design — creating the samenesses of disparate, ostensibly unconnected places — that is another thing. Chayka shows how the apps with their algorithms affect what gets built as much as how you find them.

To uncover that process and its connection with algorithms, Chayka’s choice of coffee shops is apt: “They were spaces of consumption, in which members of a certain demographic, who were also very active on the Internet, expressed their personal aspirations by spending money,” he writes. “The café space integrated aesthetic decisions across architecture, interior design, and tableware. They showcased trends in both beverages and food.”

Those “members of a certain demographic” all have Instagram accounts of course. And what do you suppose they publish to their account?

It’s perhaps a bit oversimple to say that the Instagram platform informs the look of the “generic coffee shop,” but it does — even to the point that coffee shops have incorporated “Instagram traps,” “Instagram walls,” or, heaven forbid, become an entire production set for posts from “Instagram Museums.” In the section of the chapter bearing the subheading “Generic Café Owners,” Chayka applies a telling metaphor to these physical spaces: “The [café] installations were a physical form of search-engine optimization; rather than including keywords on a website, the Instagram walls ensured that as many photos of a place as possible would exist on digital platforms, building a wider footprint.”

That is to say, the physical spaces themselves exist because of the algorithmic settings and whims of the platforms.

Chayka admits that he’s happy to see that the trend has faded, but it still persists and has even spread beyond caffeinated places: “Though the walls have become cliché, the way they work has been dispersed into every aspect of spaces and places, which began to optimize for what we called ‘Instagrammability.’ ”

Chayka’s chapter on “Algorithmic Globalization” spells out not only the process of algorithms shaping the physical world but the history of the process and people who have observed it in the very-much-pre-Internet days. That’s satisfying to people like me who like history and tend to read the footnotes.

In telling that story of algorithms and places, Chayka explains why Augé and Koolhaas would notice the “flattening” of airport spaces. The sameness grew from connection and travel, with the effect of standardizing experiences simply to make destinations anodyne. Chayka cites Gabriel Tarde’s The Laws of Imitation, published in 1890, which blamed the sameness of hotels, clothes, and all sorts of goods on — what else — passenger trains, a fairly new and very disruptive technology in its own right. “Places that connect gradually grow to resemble each other in certain ways simply because of their interconnection,” Chayka explains. “The faster the exchange, the faster the similarity sets in.”

Of course, the speed of trains was formidable for the nineteenth century, but the speed of today’s social media is not even comparable. A speedy sameness grows in the physical world as the rules of Instagrammability sets itself into the bricks and mortar of the physical world. (You can get a lot of help on the web to help you design your coffee shop. Instagram account required.)

In Filterworld, culture no longer nourishes you. Its algorithms serve other purposes … or their own.

The Internet is big, and so it’s just obvious that some sort of filtering mechanism has to help mere mortals fish useful things out of it. That’s the role of Google and its genius: providing access to things that are relevant to interests, distilled from search terms. Search is essential, and for a while Google’s service nourished interests rather benevolently, perhaps living up to its now muted motto, “Don’t be evil.”

Chayka lays out how algorithms that have helped us access the Internet also serve other purposes, many driven by demands of business and others more mysterious epiphenomena, the “unintended consequences” of algorithmic life. He calls products of algorithms “a Frankenstein phenomenon, invented and given power by humans but far surpassing their expected role…. Recommender systems run rampant. Perhaps we tend to overlook their capriciousness within the cultural sphere because the material that they influence seems less important than, say, running water.”

For Molly Russell, the algorithm had truly malevolent effect. She died by her own hand in November 2017 at age fourteen. Chayka tells her story at the beginning of chapter five, “Regulating Filterworld.” Russell suffered from depression, but the senior coroner for north London, Andrew Walker, brought “online content” into the explanation of her death: “She died from an act of self-harm while suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content,” Walker decided.

Chayka tells the story in order to highlight wayward algorithms — those “systems run rampant.” “[T]he algorithmic feed could assemble an instant on-demand collection, delivering what Russell may have found most engaging even though it was harmful for her,” he writes. “The tragedy of Russell’s case demonstrates how the problems of Filterworld are most often structural, baked into the ways that digital platforms function.” The platform’s bakers, to extend the metaphor, don’t often know the interactions and consequences of all their ingredients, but many social media platforms know a great deal about engagement, usually a prime metric and a benefit to profits.

Ah, engagement. Captured eyeballs and minds translate into cash for online platforms.

The section of the book offers some regulatory means by which digital Frankensteins might be contained. They are usually not anything that hasn’t been used effectively before, but Chayka notes that regulation alone is insufficient. Transparency, for example, does not itself lead to meaningful control, as Mike Annany and Kate Crawford note (and Chayka quotes).4 Reassessing the notorious “Section 230” in the US 1996 Telecommunications Act also might be wise, since the state of the internet in 1996 is quite different from the internet in 2024. “The problem with Section 230 is that ultimately, and bizarrely, the law makes it so no one is currently responsible for the effects of algorithmic recommendations,” Chayka correctly points out.

Chayka’s discussion of regulation is a great and sensitive summary, showing a range of regulatory options that have been applied to other areas of media, such as children’s television. Successes of previous regulation — including the ambitious framework of Europe’s GDPR — might guide US regulation for the Internet.

But in the end, governmental regulation also ends up being inadequate, Chayka says. “We must also change our own habits, becoming more aware of how and where we consume culture rather than following the passive pathways of algorithmic feeds.”

In effect, we have to take on roles we have carelessly let slip. That in itself is a call for a new cultural moment, one that Chayka understands to be a turning away from algorithmically delivered “content.” We need to overcome, somehow, a cultural helplessness learned from the algorithm.

Chayka took on an “algorithm cleanse,” and I remember his post when he hung up on feeds, beginning September 1, 2022. He turned away from social media, but he wasn’t completely untouched by algorithms. (Google and the New York Times app use them behind the scenes, he noted.) “What I’m left with is using my friends as human content filters. Rather than social-media feeds, I spend time in group chats, one in Slack that I’ve been in for many years, and others in the chat app Discord, which was originally designed for video games.” He had reverted to practices that were once common back a decade or so.

Chayka’s account of his “algorithm cleanse” begins the book’s last chapter, in which, I suppose, one could say that the cleanse exposes a new/old way of consuming culture. In it, Chayka goes “In Search of Human Curation,” the chapter’s title. Curation is the active human supplement for the guardrails that might be erected in Internet regulation, but curation is also the means by which we humans create cultural contexts and ways we live meaningfully within them. It is an ancient practice, and as Chayka describes it, curation appears as “care.” The word’s history emphasizes “the caretaking of culture, a rigorous and ongoing process.”

WE HAVE TO TAKE ON ROLES WE HAVE CARELESSLY LET SLIP. THAT IN ITSELF IS A CALL FOR A NEW CULTURAL MOMENT, ONE THAT CHAYKA UNDERSTANDS TO BE A TURNING AWAY FROM ALGORITHMICALLY DELIVERED “CONTENT.” WE NEED TO OVERCOME, SOMEHOW, A CULTURAL HELPLESSNESS LEARNED FROM THE ALGORITHM.

I particularly enjoyed this chapter, I think because the stories that Chayka tells of his own de-tox of algorithms and the curators he features (a MoMA curator, a DJ, and a film collection producer). The concept of curation comes alive in the telling. Curation concludes the book, and serves as a beginning and a challenge for readers — a way out of the learned helplessness of Filterworld.

In this final chapter, Chayka invites us to reject the algorithm as arbiter of culture, taste, and even of our own identity.

To resist Filterworld, we must become our own curators once more and take responsibility for what we’re consuming. Regaining that control isn’t so hard. You make a personal choice and begin to intentionally seek out your own cultural rabbit hole, which leads you in new directions, to yet more independent decisions. They compound over time into a sense of taste, and ultimately, a sense of self.

Adding to knowledge of the processes of “tech” in society and culture

Chayka’s book adds to the ever-active discussion of the influences of technology on society and culture, and specifically to the strain of argument that focuses on processes of “tech” — the mobile and computational technologies that surround us today. Here are three examples of how Chayka’s focus on algorithms and cultural transformation and flattening play out in work by some others. (These examples were right to hand, and I just grabbed them. They’re not rare beasts.)

Cory Doctorow coined the term enshittification, which is how Internet platforms develop, decline, and die — in effect setting the terms by which algorithms are deployed in platform products.5 In part — and maybe even a large part — the process of decline is enacted by what Doctorow ominously labels “The Algorithm” (note his Scary Capitals) which is changed for the sake of squeezing out profit. The changes often amount to narrowing access or narrowing selection to user contributions, which are after all cultural products. And, of course, encouraging “engagement.”

Levin Brinkmann and colleagues offered a “perspective” in Nature Human Behavior in November 2023. The article, entitled “Machine Culture,” points out that “[r]ecommender algorithms are altering social learning dynamics. Chatbots are forming a new mode of cultural transmission, serving as cultural models … [and] intelligent machines are evolving as contributors in generating cultural traits.” At the end of the article, the authors propose “grand challenges and open questions,” including issues of “societal decision-making.” Although the authors focus more narrowly than Chayka on AI and “intelligent machines,” they observe paradoxes of culture that Chayka describes and see them as an area for more thorough study. Despite the diversity of projects in AI, they write (in accord with Chayka) that

market forces, such as regulation and market power, may result in a world dominated by a small number of monolithic models. This raises the possibility of reduction in cultural diversity, as major social, political and economic forces try to shape global machine culture to match their preferences…. Conversely, we face a potential ‘Tower of Babel’ scenario. As AI models become increasingly personalized, conforming to and reinforcing our individual worldviews, they risk engendering an unprecedented fragmentation of our shared perception of the world.

Brinkmann, et al. propose a framework that may be useful for studying “machine culture.” The framework takes “the key properties of evolutionary systems” into consideration: “variation, transmission, and selection,” all three of which are present in Chayka’s book, which also reveals the close interplay of each.

Closer to home,

recently spelled out how changes in the early and quite simple Substack infrastructure turned Substack into an algorithmic “platform” and transformed its environment so much so that “[b]y 2023 … Substack no longer could claim to be the simple infrastructure it once was.” Substack had “evolved”:It began encouraging individual writers to recommend one another, funneling tens of thousands of subscribers to like-minded people. It started to send out an algorithmically ranked digest of potentially interesting posts to anyone with a Substack account, showcasing new voices from across the network. And in April of this year, the company launched Notes, a text-based social network resembling Twitter that surfaces posts in a ranked feed.

The complications that ensued even had to do with Nazis, as almost all Substackers have learned by now. Newton points out that the algorithmic developments in Substack were not merely a matter of adding “infrastructure”; they changed the nature of the community in ways that might be somewhat predictable but also with unintended consequences. (I think Newton sees the consequences as arising in large part because of naïvety and the wishful thinking that abounds among tech-bros. I’d agree.)

The point, of course, is that algorithms direct attentions, and the process of flattening, in Substack’s case, could well have been a flattening into the mold of a “Nazi bar.”

A final observation about the book’s method

Filterworld, like The Longing for Less, weaves Chayka’s experience — stories from his youth, his routines, even experiments he conducted while writing the book — with interviews and library research done for the book.

That personal touch is not unique to his writing, of course, but I think his writing profoundly succeeds with it. When it comes to ways that we consume culture or, for that matter, even be in today’s world, Chayka’s skillful relating of his inner experience with his subject creates a well-marked pathway for his readers to follow. We can shift our gaze from tiny screens to consider the choices that we surrender to algorithms in our Filterworlds.

We can once again choose. We can curate ourselves anew.

Filterworld book tour information. If you’re in Washington DC, New York, Cambridge MA, Los Angeles, San Francisco, or Tucson, you can hear Kyle Chayka talk about his book.

Kyle Chayka has two newsletters on Substack:

and he is a contributor to a new “beta” newsletter that is exploring curation in the 2020s:

Related posts on Technocomplex

Got a comment?

Tags: social media, algorithm, filter, Kyle Chayka, control, manipulation, culture, identity, curation

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Chayka, Kyle. “AirSpace, Redux.” Substack newsletter. Kyle Chayka Industries, October 7, 2022.

Ezra Klein Interviews Kyle Chayka. Interview by Ezra Klein. Transcript. New York Times, January 9, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/09/podcasts/transcript-ezra-klein-interviews-kyle-chayka.html.

A measured look at Substack, its “infrastructure,” and the algorithmic doors opened to intolerance and hate. Newton, Casey. “Why Substack Is at a Crossroads.” Platformer, February 9, 2023.

Darned locomotives! It is good to see a century-old book resurface in a book of the 2020s. Tarde, Gabriel de. The Laws of Imitation. Translated by Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons. New York : H. Holt and Company, 1903. http://archive.org/details/lawsofimitation00tard. “To-day, the same kind of comfort in food, in dwellings, and in clothing, the same kind of luxury, the same forms of politeness, bid fair to win their way through the whole of Europe, America, and the rest of the world. We no longer wonder at this uniformity, a condition which would have appeared so amazing to Herodotus…. [T]he modern continental tourist will find, particularly in large cities and among the upper classes, a persistent sameness in hotel fare and service, in household furniture, in clothes and jewelry, in theatrical notices, and in the volumes in shop windows” (p. 323).

The first chapter lays out types of models, including the model used in O’Neill’s kitchen. O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. First edition. New York: Crown, 2016.

Brinkmann, Levin, Fabian Baumann, Jean-François Bonnefon, Maxime Derex, Thomas F. Müller, Anne-Marie Nussberger, Agnieszka Czaplicka, et al. “Machine Culture.” Nature Human Behaviour 7, no. 11 (November 2023): 1855–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01742-2.

Contortions of art for TikTok? Seabrook, John. “So You Want to Be a TikTok Star.” The New Yorker, December 12, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/12/12/so-you-want-to-be-a-tiktok-star

Word of the year in 2023, according to the American Dialect Society. Doctorow, Cory. “Pluralistic: Tiktok’s Enshittification (21 Jan 2023).” Pluralistic, January 21, 2023. https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/.

Yes, maybe it’s time. Chayka’s book supports the argument. Newport, Cal. “It’s Time to Dismantle the Technopoly.” The New Yorker, December 18, 2023. https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/its-time-to-dismantle-the-technopoly.

By the way, I’m waiting for the yellow flower print in the grunge theme! Collins, Lauren. “Tagwalk Takes on the Hemline Index.” The New Yorker, January 1, 2024. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/01/01/tagwalk-takes-on-the-hemline-index; and Paton, Elizabeth. “Tagwalk Wants to Be the Google of Fashion.” The New York Times, July 5, 2018, sec. Style. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/style/tagwalk-fashion-search-engine.html.

Marx (not that one from the nineteenth century) looks at technology and social media, too, though with a focus on the processes of status seeking and the development of “taste” and culture. Marx and Chayka have complementary, though not always overlapping views. Marx, W. David. Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Higher Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change. New York, NY: Viking, 2022. “As we know, technology doesn’t automatically change culture. People using that technology must move from old conventions to new ones. So we must look at both how the technological, economic, and social changes of the internet age set new parameters for our actions, and how we have adjusted our status strategies accordingly.”

The print edition title is “Designer Data.”

Quotes for the initial publication of this review come from an advance reader copy, which declares: “This is an uncorrected proof. Please note that any quotes for reviews must be checked against the finished book. Date, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.” I quote, maybe even extensively. But I’ll check things once my regular old copy arrives.

I recall noting the change in the 1970s to the 1990s myself, when I landed a few times in Frankfurt am Main’s airport. The most obvious and annoying shift for me was linguistic: English had so overtaken the place, it seemed. The airport had become an everywhere, rather than a destination that was different, and even the language had become the same, point-to-point.

It’s a common error to think that “transparency” implies control, but the connection is weak. Transparency may lead to an understanding of possible ways to control, no more. There are examples from other industries. Lilian Edwards and Michael Veale point out, “As the history of industries like finance and credit shows, rights to transparency do not necessarily secure substantive justice or effective remedies. We are in danger of creating a ‘meaningless transparency’ paradigm to match the already well known ‘meaningless consent’ trope.” (Edwards, Lilian, and Michael Veale. “Slave to the Algorithm? Why a ‘Right to an Explanation’ Is Probably Not the Remedy You Are Looking For.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, May 23, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2972855.)

Doctorow lays out the process that the term represents in the first paragraph of his post: “Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

I’ve been looking forward to this Mark, and you’ve done it in your distinctive DeLong style: filled with cross-references and footnotes, which I always like. Something tells me this one will get a second read, since your ideas are all banging around in my head now ...

Added to the reading list, thanks to the ideas of algorithmic “sameness” in the meat space and of personal life curation. Great review, Mark.