Book review: Populuxe

From the backlist. An era that hoped for so much wealth that no one need share: mid-1950s to early-1960s America. A decade of "joyful vulgarity."

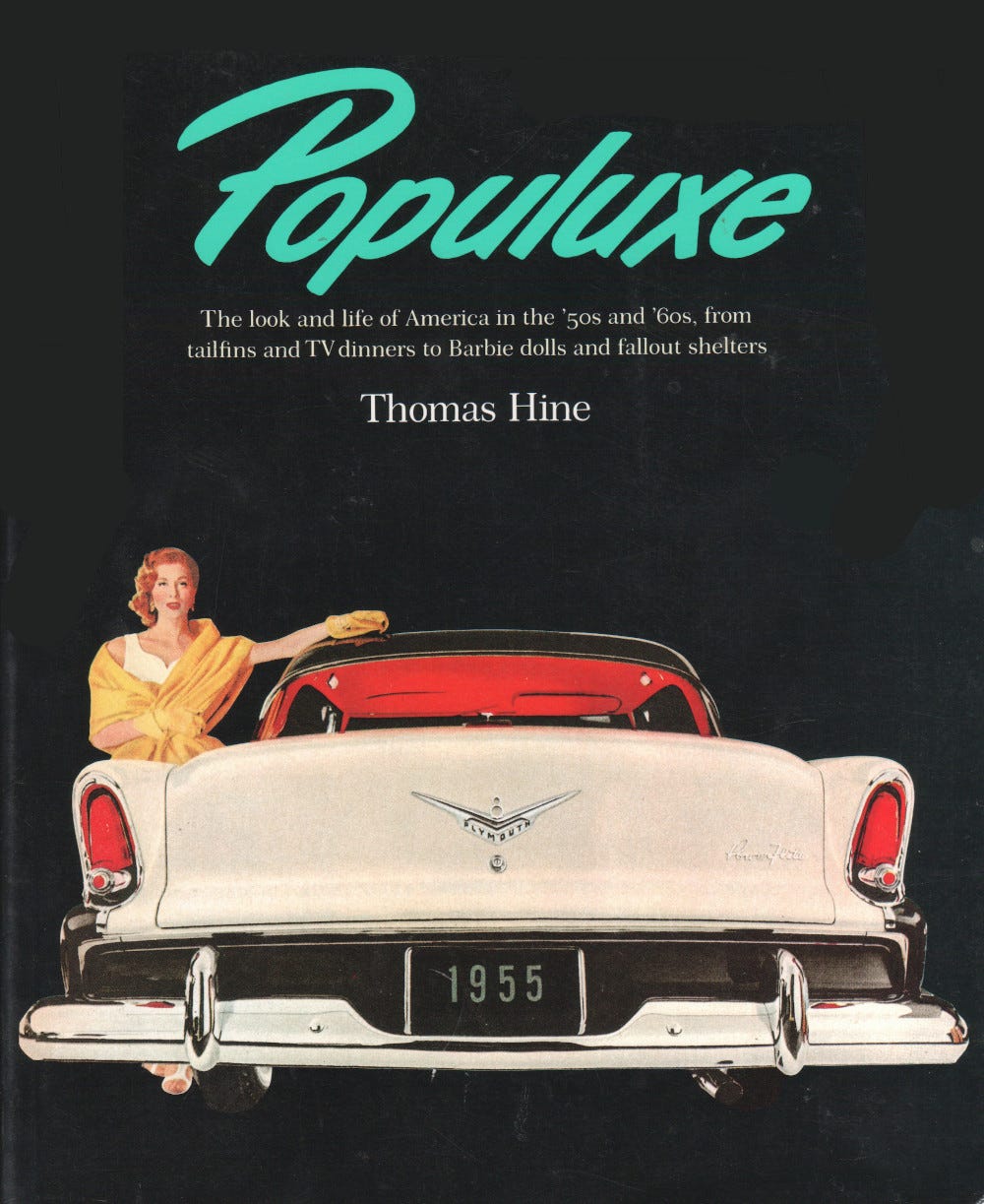

Read time: about 12 minutes. Once a quarter, I take a look at a book, alternating between recent releases and books on the backlist. This week I pull a book from the backlist shelf, Thomas Hine’s Populuxe, first published in 1986.

Share this one with someone?

If you got this from a friend who shared it, how about getting your own copy? A subscription is free, and it’s only another email.

From the start, the pictures had me.

Profusely illustrated, Thomas Hine’s Populuxe dazzles. But here’s the thing: When you look at the illustrations and the photographs, the kaleidoscope of 1950s advertisements and snapshots come close to their own parody.

Hine, Thomas. Populuxe. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986. 184 Pages. ISBN: 0-394-74014-9 $16.95. Reprint edition, “with a new preface by the author”: Overlook Press, 2007. $60.98.

Eyes in Boomer heads, like mine, look at the images today to see a completely different world than our youthful eyes beheld over a half-century ago. Hine recognizes this tension — ideas contrary and held in readers’ minds simultaneously — and handles it honestly and unsentimentally. A tough task for a writer.

He explores the odd juxtaposition of wide-eyed 1950s hopes and late twentieth-, early twenty-first-century jadedness in the book’s last chapter, “The End of Populuxe,”1 and demarcates these perspectives of hope and jadedness with the opening of the 1964 New York World’s Fair. He writes that

by 1964 it was becoming clear that the look — and the meaning — of things was starting to change. The imagery that had enlivened the previous decade had begun to look embarrassingly naïve and even empty. Pop artists had discovered it, and began to to produce images that were, at once, familiar and accessible, but ultimately subversive. Once you become self-conscious about your fantasies, they can never again be quite so satisfying.

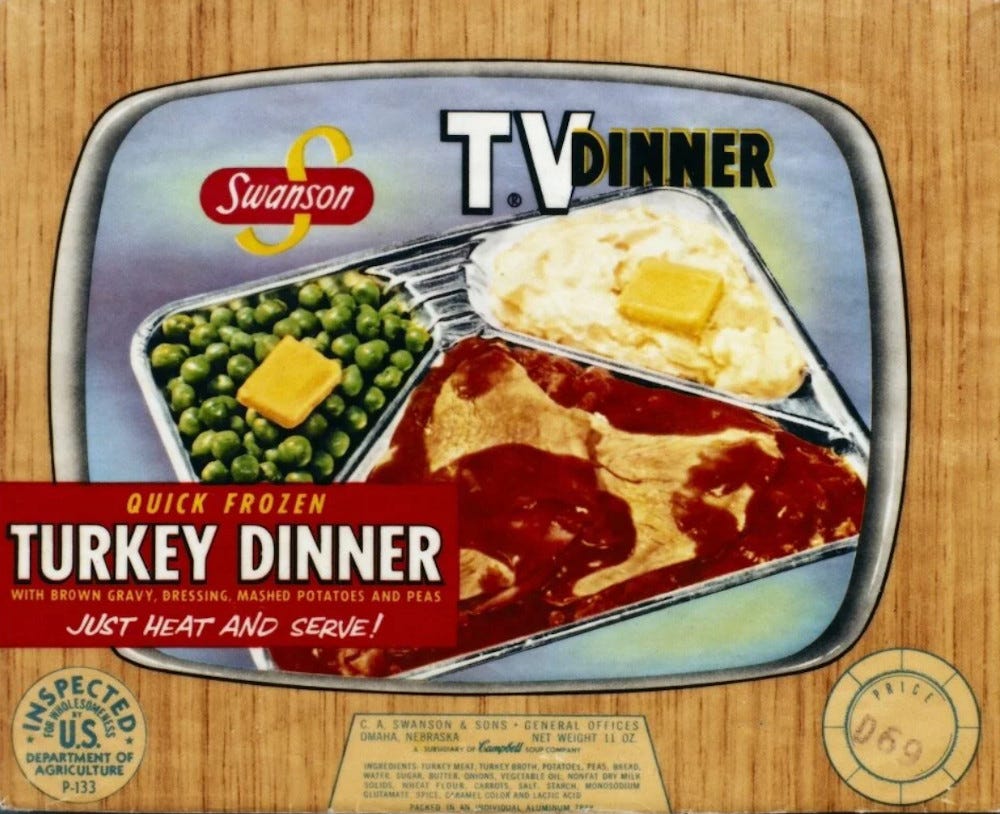

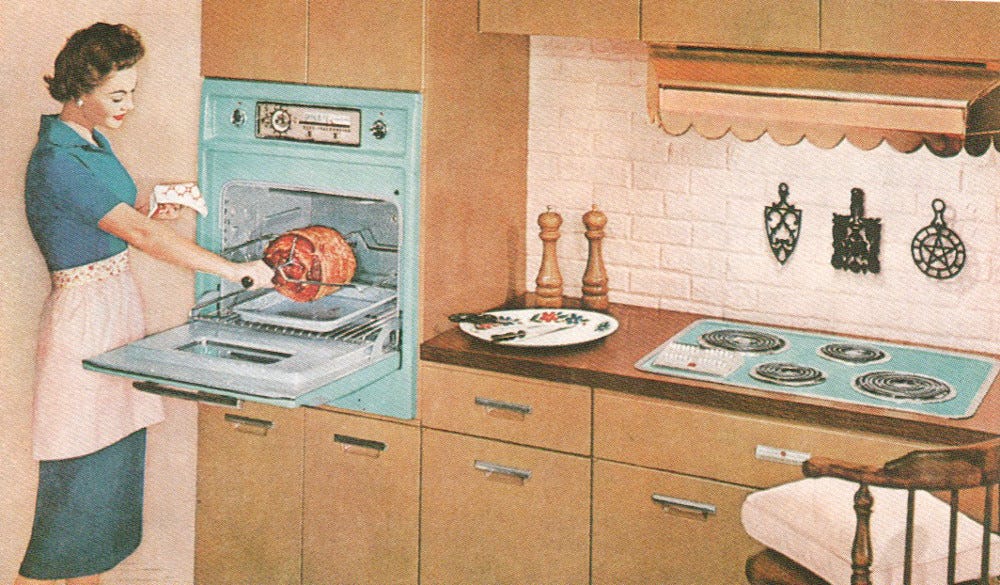

Hine uses the washing machine — mechanical emblem of 1950s “labor-saving” marvels — to illustrate the shift. “In 1959 Nixon could use a washing machine to symbolize America” — and, I should add, he did … to Nikita Khrushchev — “but in 1964 it would have been ridiculous.” By 1964, the neat world of rocket-shaped vacuum cleaners, push-button convenience, and TV dinners had met a harsher reality that, in truth, had been there all the time, hidden beneath a Formica façade of American post-war enthusiasm.

Even the darling of American culture, the automobile, also became a focus of friction. The first Ford Mustang was unveiled at the New York World’s Fair. Turning lazily on a hubcap-like turntable, the Mustang was surrounded by a civil rights demonstration. Protestors ringed the exhibit, locked together cross-armed, hands firmly clasped.

Hine counts the Mustang debut among the “phenomena that seem to mark the end of Populuxe,” the name Hine coined for the era beginning in 1954 and ending a decade later. His book defines Populuxe.

Of course, the word itself mashes popular with luxury, and it is Hine’s invention, not a word of the time. He spices up the word with a “thoroughly unnecessary ‘e,’ to give it class … [a] final embellishment of a practical and straightforward invention is what makes the word Populuxe, well, Populuxe.”

Defining an era with a word is like describing a fragrance. There’s a challenging leap between the conceptual and the sensory that seems to lack words sufficient to the task. (I am amazed by advertising copywriters pitching perfumes.) Hine chooses to define by accretion, since Populuxe in design “is more an attitude expressed by a family of looks, a series of options added to such utilitarian objects as a Levitt house or a bottom-of-the-line Plymouth.” Populuxe embraces bad taste or, if not exactly bad taste, then certainly not good or “educated” taste either. “The essence of Populuxe is not merely having things,” he writes, using the hot word essence. “It is having things in a way that they’d never been had before, and it is an expression of outright, thoroughly vulgar joy in being able to live so well.”

Luxury by nature is singular (or at least infrequent) and distinctive, popular is not. Populuxe imbued luxurious feeling to mass manufactured goods, not Faberge eggs or other singularities. It offered glistening abundance that at least impersonated prosperity and fostered a hunger for the future. As a concept, Populuxe never strayed far from being materialistic and rankly commercial. Its objects were products first and foremost, and design and its airs often garishly pointed to luxury. “What had previously been luxuries — automobiles, automatic washers, large front yards — were turning into necessities, but people still felt the need to celebrate and adorn them with features that at least suggested luxury,” Hine explains.

As a concept, Populuxe packages “vulgar joy,” a hope for newer and better things, speed, style, energy, fantasy made real life. It promises a world with so much wealth that nothing need be shared, as Hine quite revealingly put it.

A promotional piece from MPO Productions for General Motors’ “Motorama” (1956). GM cars are featured, but also dreams of future kitchens, which the film creators seem to think is the appropriate place for women, with aprons of course. So goofy today, it feels almost psychedelic. But it’s Populuxe!

The book describes Populuxe in chapters exploring material culture of the age, with a constant reminder of the elements of desire and feeling that underlay (and maybe enriched) its products. Cultural context meets material to form a riddle of the Populuxe experience, and Hine teases out elements of that experience.

Populuxe motors and dreams

I’ve chosen three chapters that provide a picture of the general method of the book, though in such a summary form that I hope you’ll realize that Hine’s writing has much finer texture and detail. And he casts the whole with humor as well.

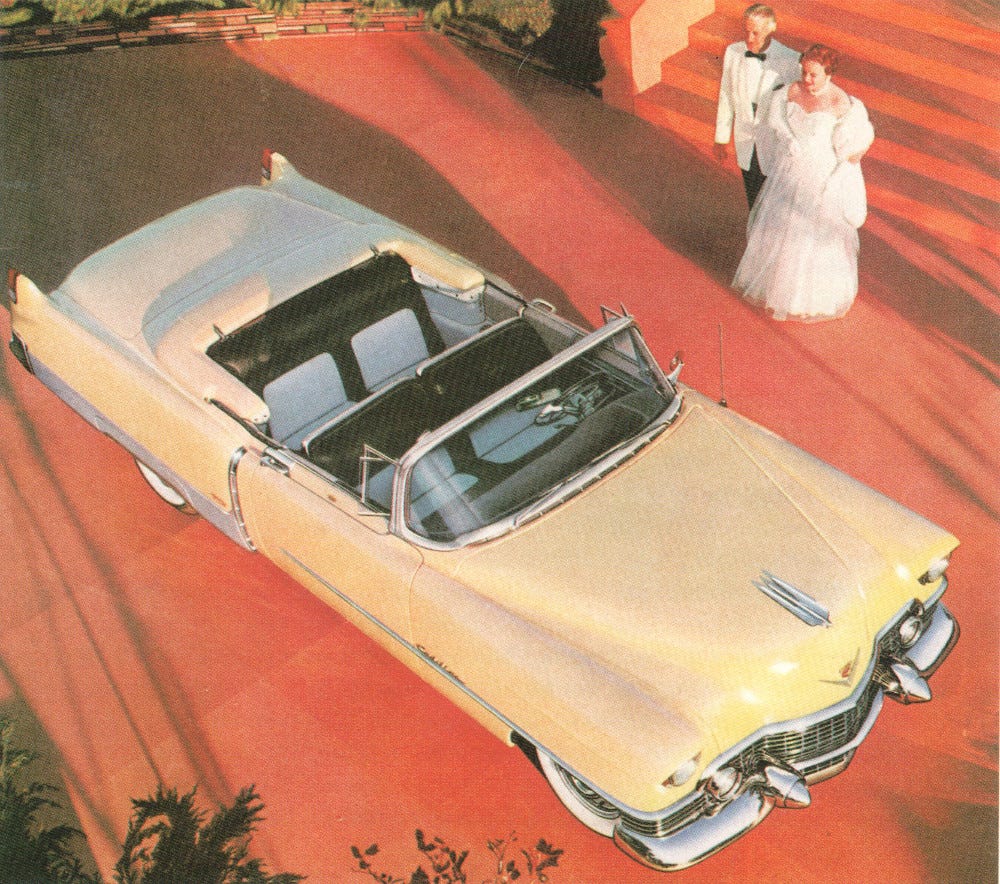

Because the automobile looms over so much of Populuxe life, it makes sense to start with the book’s fifth chapter, “The New Shape of Motion.” Changes in the car market may have crystallized some of the features of Populuxe, such as an increased attention to design — as in flair, frills, and ornament — and a more urgent press of advertising and marketing currency and “newness.”

This was in large part a survival tactic.

For a decade or so after World War II, American consumers attempted to catch up. Times were good for car companies in particular, up until summer 1953, when the thirst for new cars was slaked — a trend that car makers were aware might happen. “Some important things began to happen at that point,” Hine writes of August 1953, when the market shifted.

The overall number of cars stopped increasing. Chrysler Corporation, whose cars were the most conservatively designed, suffered sharply reduced sales, while Chevrolet held steady, and Ford, which had the raciest 1953 and 1954 designs, picked up about as many new buyers as Chrysler lost. The great expansion of the auto market was over, as nearly everyone who needed one had one.

Car manufacturers feared that the market was saturated.

Detroit brought together bold and “forward” styling, a sense of innovation and progress, and, perhaps most important, a spur of dissatisfaction with the old-but-serviceable in hopes of reinvigorating car sales. It worked. And when applied throughout culture and the economy, design and impatience for the new laid a foundation that American industry could build upon. What William M. Schmidt, a Chrysler Corporation car stylist, said of his profession could be applied generally to anyone else “styling” consumer products: “We’re really merchandisers.”

Hine carefully lays out design decisions that the car companies made in the mid 1950s to the early 1960s, and he weaves stories of the designers — colorful characters in their own right — into the history of the “rolling jukeboxes” of Populuxe.

Relating to a beautiful detail of 1950s car design, you might like to read:

“The Boomerang and Other Enthusiasms” starts off with a meditation on jukeboxes — its adoption in the front ends of American cars of the 1950s (much disdained by Raymond Loewy, Studebaker’s chief designer), its physical transformation from a heavy box in the era of Glenn Miller and his Orchestra to the “airier-looking” sonic powerhouse for Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry, its sprouting of satellites in restaurant booths for remote control of the music. “Dynamism and fragmentation, the two tendencies exemplified by the jukebox, dominated the imagery of the Populuxe era,” Hine summed up.

The chapter examines some characteristic shapes, most notably the boomerang, which Hine links back to aviation. Winged shapes invoke movement and speed — both Populuxe virtues and desires — and as you read through the chapter and look at its illustrations you see how pervasive the form became. The boomerang shape was put into service as Chrysler Corporation’s logo, molded into ashtrays (some made of scorchable thermoplastic), fashioned into foldable chairs, made dynamic in Alexander Calder’s floating mobiles, firmly planted as McDonalds’ golden arches, carved into living room coffee tables, and upholstered into swooping couches.

The boomerang shape and the rocket wings they resemble were everywhere in Populuxe products.

The beauty of this chapter, like the others in the book, draws from Hine’s way of bringing Populuxe products into relation with culture, which was already mainly a consumer culture. Linked by consumer choices exacted from dreams that advertisers had shaped, the shapes of the age coalesce with desire and feeling.

That’s a big task for a shape, especially when it takes form in an ashtray.

“Lost in Space” presents starkly contrasting architectural movements — the modernist spirit of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe against the ebullient, glitzy, and (frankly in my view) joyfully tacky spirit of Morris Lapidus, who were, “respectively, the superego and the id of American architecture.” Of the two, Hine declares,

Only Lapidus could be labeled Populuxe, of course. Indeed the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach might stand as the definitive Populuxe monument. From the moment Lapidus’s client told him, ‘I want that nice modern French provincial,’ it seemed destined to be a perfect embodiment of the zeitgeist.

The opening night in December 1954 supported Hine’s judgment: the hotel was declared the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” That declaration was made by none other than Groucho Marx, to music supplied by Liberace. Case closed.

The Fontainebleau Hotel, by the way, has been restored and reopened in 2008. You can still “swan” down the “stairs to nowhere,” although you should know that the stairs do have a destination — a coat room at the top.

THE BEAUTY OF THE CHAPTER DRAWS FROM HINE’S WAY OF BRINGING POPULUXE PRODUCTS INTO RELATION WITH CULTURE, WHICH WAS ALREADY MAINLY A CONSUMER CULTURE. LINKED BY CONSUMER CHOICES EXACTED FROM DREAMS THAT ADVERTISERS HAD SHAPED, THE SHAPES OF THE AGE COALESCE WITH DESIRE AND FEELING.

Mies carried on with glass planes and steel girders — clean lines in contrast with Lapidus’s extravagance. Mies was the more famous of the two and was, according to Hine, “certainly a much more important role model to architects who considered themselves to be serious.”

“Lost in Space” contrasts their architecture and lays out their meanings for the people of Populuxe, which in the case of Mies unfortunately boiled down to cost. A real Meis building was expensive, but imitations were cheap. However, Meis-like stark lines made for spaces that to many felt “unlivable.” Lapidus was tacky, sure, but his spaces pleased middle-class fantasy with a hodge-podge of styles. And that, for Populuxe, made his spaces memorable. Destination-worthy.

In my view, Hine’s discussion of Populuxe architecture in this chapter is the best of all the book’s chapters, probably because he could draw from his deep knowledge of architecture and design. He was architecture and design critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer. This chapter includes other architects who made up the “built environment” of the 1950s and 1960s. Of course, among them is Frank Lloyd Wright with what Hine calls a “more organic approach” to space than “Mies’s icy abstractions.”

Naturally, there are strip malls (not Meis’ or Wright’s or even Lapidus’ fault).

Hine places Populuxe into a larger historical frame, and he helps readers understand “the idea of modern space” that, he says, originated a century before Populuxe emerged with “the arrival of iron-frame construction in such building as London’s Crystal Palace of 1851.” All of a sudden, the whole idea of walls and windows changed because of new technologies. Beyond that, during the widespread Populuxe adoption of television, the built environment could rely on TV’s immediate and expansive connections; TVs delivered “a succession of experiences … as intense and vivid as life itself. And you didn’t have to be in New York or anywhere. Your little raised ranch on the cul-de-sac was plugged in.”

That Hine pulls together seemingly separate realms as suburban architecture and, well, Hollywood fantasy represents the Populuxe era complexly, and I think well. The era itself brought them together effortlessly. Hine explains them.

Two-minded sight

Maybe it’s just me.

Still, it could be that the odd detachment that Boomers (like me) have from their own experience of the age comes from the enormous shifts in modern culture that have followed. The lens through which we young Boomers viewed Populuxe products no longer has its magic now that we Boomers (and America) are older and perhaps a little wiser.

Hine brings us through this world of Populuxe. Through his book, Populuxe resides in our readerly heads, but we behold the illustrations and the photographs of the first eight chapters already having lived through the eclipse of the era that Hine’s final chapter describes.

In 1955 or so, our grandparents looked at the magazine photo of the white woman wearing a gingham apron in her turquoise-applianced kitchen with orange Formica countertops. They consumed the image with a certain post-war reverence and desire. Their heated up Swanson TV dinners really felt as special (or at least “space age”) as they were handy.

Today, our eyes fall on the same photo. But what we see is profoundly different: a relic of a constrained age with even frighteningly rigid gender roles, a carelessness of consumer waste, hidden and significant environmental costs, frankly preposterous expectations of the future, and invisibly lurking injustices. Grandma and Grandpa smiled back at the smiling woman in the magazine photo, but our view of it today is ironic, even mocking.

That juxtaposition of views — the 1950s v. an ironic or, for some, a nostalgic gaze today — makes Hine’s book a pretty complicated read. Thank goodness his prose is crisp, fresh, and amusing. Throughout, I watched myself reading myself or, better put, I engaged in two-minded sight, at once recalling like images from my past while subjecting them to my latter-day, and quite critical, judgment. For I spent part of my childhood swept up by the glamour and excitement of the 1950s and early 1960s, but now, as an adult in the 2020s (a grandparent myself, at that) I can’t help but see the photographs of the 1950s through complex lenses that more recent history provides.

It is hard to be wistful about the age of Populuxe. But it’s also, paradoxically, somehow easy (for Boomers at least). That is the consequence of two-minded sight.

Tags: popular culture, design, 1950-1960, US, post-war America, built environment, kitsch, automobile, car

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Enjoyable and informative: Architect Breaks Down Why All American Diners Look Like That. YouTube video. Architectural Digest, 2023.

A Times review of Hine’s Populux from 1986: Kakutani, Michiko. “Books of the Times.” The New York Times, October 29, 1986, sec. Books, p. C22. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/29/books/books-of-the-times-547986.html

A short piece related to Lisbeth Cohen’s book that describes the period after Populuxe. It’s an interview with the author. Silverthorne, Sean. “A Consumer’s Republic - How We Became a Consumers’ Republic.” HBS Working Knowledge, February 10, 2003. http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/3262.htmla-consumer-s-republic-how-we-became-a-consumers-republic.

Here are the chapter titles: “Taking Off,” “The Luckiest Generation,” “A New Place,” “Design and Styling,” “The New Shape of Motion,” “The Boomerang and Other Enthusiasms,” “Just Push the Button,” “Lost in Space,” “The End of Populuxe?” Acknowledgements, index, etc. follow.

Great read, might have to add it to the list.

The design is so distinctive; the infusion of what was felt to be “space-age” is a hallmark of the design - the boomerang like a satellite, the fascination with chrome, the typefaces with stylized asterisks and starbursts - yet it never lasted beyond the first decade of the space race. I think the point made about mocking the associated naïveté hits the nail as to why it didn’t last, but I find the change interesting (that it was no longer seen as “wonder”, perhaps, but as being naïve). I’m fascinated more so because now, there’s some return to it - wide-eyed cartoon characters, “brutalist” graphic design, a space-y quality to colour choice and sharp lines.

Another fascinating read, Mark - I've enjoyed this dive into mid-century US culture!