Pour it in a different glass

I started a screenplay and found my perception changed. An essay about form and perception, genre and writing.

Read time: about 12 minutes. This week: I use screenwriting to try to think differently. What genre and form do to help us perceive and understand. Next week: I’ll probably go off on certain chrome bits that were especially popular on cars some decades ago. Known as mascots, they leaned over radiators and car hoods.

Remember, The Boulangerie offers glimpses of what’s in a warm place rising or already in the oven. This past week: a musing on contradiction and inconsistency and an snippet on engineers and truck mechanics. I only announce when something happens in the Boulangerie with my Mastodon loudspeaker: @mrdelong@mastodon.online.

I think you should share this piece with someone you know! And if you got it from a friend, won’t you hit the subscribe button?

Caroline Thompson, the screenwriter who worked on Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas, The Addams Family, and The Secret Garden, said it best: “Writing a script is so much like writing a sonnet: you have very specific boundaries in which to shape a story.”

Boundaries channel expression just as surely as they shape thought and perception. The boundaries of form prod the writer to a certain intelligible shape of story and thought. I experimented with a form of writing in order to see a situation anew. Instead of an essay, I decided to write a screenplay, because a screenplay imposes quite different boundaries. Its boundaries also reveal.

My backstory. Why a screenplay?

I’d explored screenwriting before, though hardly with the rigor of a professional. I’d scripted short videos and experienced having them chopped mercilessly by a producer as we went through production. Once, after an off-hand quip by a friend, I quickly concocted a TV pilot, mostly comic, featuring the escapades of a gormless and failed Presidential candidate in dreary and cold Moscow. A one-off, fun thing that I didn’t share with anyone except for my quipping friend.

Get more independent writing. I recommend The Sample. They send one newsletter sample a day. No obligation. You can subscribe if you like it.

The producer I had worked with for other projects came from Disney. He was talented, funny, and ruthless in cutting. Looking back, I now realize that I had only learned what a screenplay looked like on a sheet of paper, but I had not thoroughly absorbed its logic and its restrictions. “Boundaries” of the screenplay genre were still fuzzy in my mind. If screenwriting, like sonnets, has a shape and a form, I got the iambic pentameter part right, but I was writing seventeen lines, not fourteen.

It wasn’t until I grew to worry about one of the readings I had assigned in my fall seminar that I felt I needed to “write it out” — that is, explore anew by writing about it, not as a scholar-researcher but as a human being trying to see within the situation that unfolded. The reading was by Martin Heidegger, without doubt an influential twentieth-century philosopher but also a Nazi and, I had come to believe, a much more committed Nazi than I had earlier thought. I was concerned about whether the person’s actions tainted his philosophical thought. I thought it best to see if I could explore Heidegger by what he did, not only by what he thought and wrote.1

In effect, I wanted to excise Heidegger’s philosophical contribution from my picture of the man himself.

Screenwriting might be the best form to display actions and choices, rather dispassionately, too. A screenplay doesn’t “think”; it does. As a matter of fact, a good screenplay rarely, if ever, mentions that a character thinks about something. In a screenplay, that’s an error. In his screenwriting guide, Skip Press wrote that “you should ask yourself whether you want any of the principal characters to do a lot of important thinking on the page. If you do, you have a novel.” And, presumably, not a screenplay.

If screenwriting, like sonnets, has a shape and a form, I got the iambic pentameter part right, but I was writing seventeen lines, not fourteen.

In effect, I’m screenwriting as a problem-solving exercise. I’m fashioning a plausible fiction of events, stacking up notes of actions. Inner thoughts and motivations are out of bounds. The person in my story acts — and only acts. I watch and judge. Of course, I could not indict anyone with my fiction. Still, the screenplay’s reduction has its uses; it allows me to explore more emotively and empathetically, perhaps, events that baffle and confuse the intellect.

Storytelling can be treacherous, but it can also unveil.

Form is different from format, but format is a part of form

For my current screenwriting task, I decided to learn the rules I had ignored and abide by them as best I could. My past screenwriting “work” could at best be called novelistic screenwriting. I wrote a novella, so to speak, using the format of a screenplay.

Don’t know what a script looks like? Here’s a “shooting script” which is a product of much development and collaboration: Woody Allen’s Hannah and her Sisters (PDF) from 1986. You’ll see that the screenplay format is actually quite simple, and its hallmarks shape writerly invention: Where is action taking place? What does the audience see and hear? Who talks to whom and in what manner? The key points:

Every action has a place in a scene and a time (“EXT. HANNAH’S KITCHEN -NIGHT”).

Actions appear in present tense. Only present tense. (“Hannah, licking her fingers, walks past a memo-cluttered refrigerator to the stove as Holly, behind her, begins to speak. The faint sounds of music are still heard.”)

Dialogue is surprisingly brief. At least for me it was surprising. Direction is also surprisingly minimal and in fact mostly absent.

The format is the screenwriter’s quickly wielded paintbrush. Everything is brief. No paragraph (tellingly called “blackstuff”) explaining the setting, say, is more than about three or four short sentences. Nothing elaborate. Why? Because the screenplay represents a visual and auditory product that should play in the script reader’s mind. Your reader lightly dances through your prose, which in the end presents itself as invisibly and transparently as possible.

The script evokes. No, actually more than that. It dissolves, steps aside, as the reader enters to live within scenes. The reader builds the story, finally, from what the script shows.

The reader’s brain is your screen.

Something software is good for

In some sense, the screenplay format flattens a writer’s work, since what matters is character and action and nothing else. I found that screenwriting software really, really helps, though not because it serves as a finger-wagging editor (“Uh, uh. No thoughts there!”). Rather, the software reminds you where you are in a manuscript.

I’ve used Highland 2 for scripts, and it’s really helped channel my attention as it frames and formats scenes or dialogue. A good working version for Macs is free to download, and it has useful features to get you going. The paid version is affordable, and you’d join a number of professional screenwriters if you choose it. The paid version adds some nice features, too.

Formatting is in some sense a “micro” thing. Story form is the “macro” — the ebbs and flows of a tale, interweaving subplots, and intended or focused dawdling. Highland 2 helps with this macro stuff, too, as do other screenwriting applications. I’ve found its views of my manuscript particularly useful. In the “free” Highland 2 version, these views include

an ordered scene-by-scene list of the whole story — a view that also allows you to move entire scenes into different places.

a “Bin” for notes and text. I’ve used it to define actions that I can reorder and flesh out — a flexible “to do” list.

“Statistics” that let you know how many pages you’ve written, the approximate reading time, and a report of “sprints” and “milestones.” I’ve not used the sprint/milestone feature for my current project, but many might find it useful, especially if they have a clear plan and sufficient detail about milestones in a project (and maybe a need for a taskmaster).

a list of “Assets” that you have brought into your manuscript. I’ve not used this feature yet. I have assets in a separate application.

a “Scratchpad,” which I’ve used to hold sections of my script that I’m unsure about. I just drag them into the scratchpad for later use (or deletion).

Each tab is in itself unremarkable, but together they allow you to assess your progress and see the macro flow of your script.

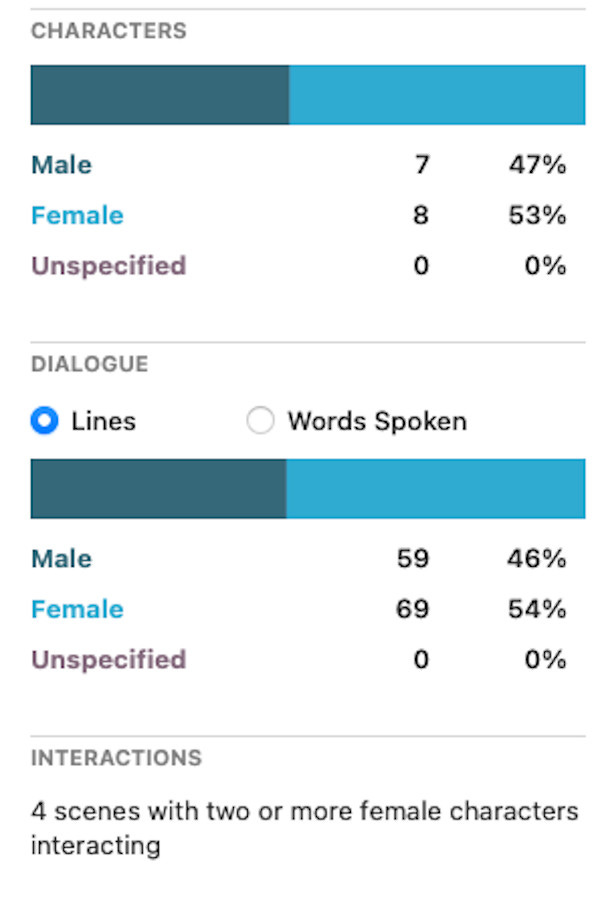

Other nice features appear in the “Tools” tab of the application. Character and gender analysis tools have been useful for this project, since they show when characters emerge and begin to fill out a human structure to the story. The “Gender Analysis” feature also compares the involvements of male and female characters in the story, and within it a feature helps writers see their progress in light of the “Bechdel test.” Other screenwriting applications include similar tools, and the paid version of Highland 2 includes a couple other features, such as “Word Analysis.”

By their nature, these analytical tools reduce scripts to numbers and relations, but they can give you a “distant reading” of a project. That’s sometimes illuminating.

From format to form

Software fails to reveal other important aspects of a screenplay, notably, conflicts, turning points, climaxes, and the like. These are action hallmarks of a story, and they often fall within “acts” of a screenplay. They draw from basic stories that establish a type. Think: the Brothers Grimm’s tales, mythology, or biblical stories. In storytelling, we may mix the basics into a new form, but we draw from a few general storylines.

I bought a few books. Really, I bought the first three used books I could find on screenwriting. I was mainly interested in the mechanics and format of the screenplay. I knew the most basic of basics, but I needed more specific guidance that held to industry norms. Two of the books were good; the third one — of the Idiot’s Guide series — was, well, hardly worth the buck I spent on it.

Screenwriting by Raymond G. Frensham clearly lays out many of the formal characteristics of screenplay stories: their flow and structure, important aspects of character development, and “literary” aspects of screenwriting. As part of the well established “Teach Yourself” series, the book is designed to help people learn the craft. Highly structured, it also includes “assignments” that build into a screenplay. It was tightly written and easy to read. I recommend it, since it covers the basics and provides a really helpful structure to an entire screenwriting project.

I also liked Syd Field’s The Screenwriter’s Problem Solver, though I suspect that the book will become more important to me at a later stage in this project. A “problem sheet” precedes each chapter, listing a dozen or so problems like “The characters are too talky and explain too much” or “Relationships between the characters are weak and undefined.” Having listed problems in bullets, Field takes them on in the chapter that follows.

These two books make a good pair. Frensham helps writers get to a script, and he includes a solid systematic process for revision, too. Field helps writers refine it in response to specific problems.

Slim chance that it’ll be produced, so why do it?

Remember that the start of my screenwriting project was the discomforting notion that I didn’t know enough about ways that a certain person’s life choices had influenced his thought and philosophical contribution. I didn’t have an expectation that I’d be writing a blockbuster, but I hoped that a literary form would discipline and channel my thinking and my perception. I wanted to see and hear in context, and a screenplay would help me do that. I was seeking to use a literary form in order to surmount limitations of my way of thinking.

My screenplay draws together a new way for me to see a reality — or maybe realities.

Joshua Rothman describes different ways of thinking in an article to appear in next week’s New Yorker. A section of the online version of the article struck me as I was thinking about this post. Rothman writes, “Scientists, mathematicians, and electrical engineers tend to be spatial visualizers: they can imagine, in general, how gears will mesh and molecules will interact” (my emphasis). I thought that historians often do the same thing in their histories and interpretations, once or many times removed from the action. Rothman goes on to report that Temple Grandin, whose Visual Thinking was published in October 2022,

describes an exercise, conducted by the Marine Corps, in which engineers and scientists with advanced degrees were pitted against radio repairmen and truck mechanics in performing technical tasks under pressure, such as “making a rudimentary vehicle out of a pile of junk.” The engineers, with their abstract visual minds, tended to “overthink” in this highly practical scenario; they lost to the mechanics, who, in Grandin’s telling, were likely to be “object visualizers whose abilities to see it, build it, and repair it were fused” (my emphasis).

I’m very much a captive of my training and my penchant for words. I’m probably a “spatial visualizer.” And so, screenwriting, with its consistent focus on concrete vision and hearing within tangible settings, seemed a way for me to move into a different mode of perceiving — one more akin to the “object visualizers.”

I want to be the truck mechanic, so to speak, and not the engineer as I remade an experience with the junk of narratives and history.

Sometimes when you read a history, you’re delighted by the characters who drive the events. History is really people doing things — guiding, suffering, living the events that together make the larger story of history. It’s the people who count. And that, it just happens, is a key that helps unlock great storytelling in the movie theater.

I’ll let you know when I complete the draft.

Got a comment?

Tags: screenwriting, screenplay, action, genre, forms of expression, perception

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Scorsese remembers a master of cinematic form and delivers a tough review of current film-making. Scorsese, Martin. “Il Maestro: Federico Fellini and the Lost Magic of Cinema.” Harper’s Magazine, February 5, 2021. https://harpers.org/archive/2021/03/il-maestro-federico-fellini-martin-scorsese/.

This is a good, easy-to-read book on screenwriting. Frensham, Raymond G. Screenwriting. Teach Yourself. Lincolnwood (Chicago), Ill: NTC Pub. Group, 1996. I should add that I’ve used other books in the Teach Yourself series. One was Teach Yourself Ancient Greek, which I dutifully went through, until I ran into the optative mood. It was just too much to teach myself, and I put the book aside. At least I learned the Greek alphabet.

There are lots of screenplay examples on the web. This one is pretty good. Allen, Woody. “Hannah and Her Sisters.” Shooting script, 1986. https://indiegroundfilms.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/hannah-her-sisters-1986-shooting.pdf

Worthwhile article on a complex topic. Rothman, Joshua. “How Should We Think About Our Different Styles of Thinking?” The New Yorker, January 9, 2023. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/01/16/how-should-we-think-about-our-different-styles-of-thinking.

Kathi Wolfe is legally blind, and yet movies taught her to see. Some lyrical writing in this piece, too. Wolfe, Kathi. “A Smirk, a Smile, a Clenched Fist: What the Movies Taught Me to See.” The New York Times, January 10, 2023, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/10/opinion/legally-blind-movies.html. “Movies have been a decoder ring that helped me make sense of the world. They’ve taught me to go beyond — to picture beyond the rainbow and wild moonlight and even to take pride in how I see them in ways not everyone does. A blur, the need to get really close, to pay exquisite attention can be beautiful.”

Idiot or not, I picked up this book for a buck, used and heavily soiled with pink highlighter by someone who also liked to color daisies and exclamation marks. I don’t want to overpay someone to call me an idiot, but I’d think about spending more than a buck. Press, Skip. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Screenwriting. 3rd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books, 2008.

Of course, lurking behind this worry about a text because of its author’s actions is the brier-filled thicket of so-called “cancel culture.” As I became more keenly aware of Heidegger’s activities, my initial response was simply to remove the reading from my list. His troublesome biography has been much discussed, as well as his abiding importance to twentieth-century philosophy. I’ve decided to keep his work in my reading list while also raising his problematic biography in importance in discussion. I had already asked students to consider his work in light of his Nazi Party membership, but in the future I think a fuller account is required. Certainly that will make students even more uneasy, but I think unease is a good first response. They’ll put together fuller responses, better thought out even if painfully worked through.

Really cool Mark, and I’m looking forward to seeing the screenplay. Seeing? Well, reading maybe. I had just read that New Yorker article the other day too, it’s a nice match for what you’re doing.

Gosh, Mark, I've learned so much from reading this post. The project sounds brilliant, and I'm looking forward to updates! Really interesting to read about the screenwriting software - those analysis tools are amazing. 😃