Simple "Horseshoe," except when slick

A meditation on learning "The Line" at VIR. It's more than just a map and mathematics.

Read time: about 8 minutes. Next week a repost, perhaps elaborated, about virtual reality.

Share.

Subscribe.

Less than a half-mile north of the North Carolina border, Virginia International Raceway, known as “VIR,” is cut out of intermittent farmlands and hardwood forests. Its most famous turn is “Oak Tree” at the southernmost tip of the Full Course, its name derived from the majestic oak tree that stood in the center of the turn radius. It fell, some say mysteriously, in summer 2013. To the north in VIR’s Full Course, the first turn, named “Horseshoe,” winds back more than 180 degrees.

I very nearly “went agricultural” — spun off track — near the end of Horseshoe. At that moment, the turn taught me a small lesson about resistance and learning. (See around 0:40 into this video to watch me spin at an autocross event.)

Resistance of tire and track, remade

September dawns often rise cool enough for a sweatshirt, but September autumn lets go of summer heat reluctantly. I knew that by midday I’d prefer to shed the shirt and drop it on the tarmac. The event I attended was an HPDE (“High Performance Driver Education”) weekend, with driving sessions interspersed with racing instruction, lectures on flag signals, and race car behaviors that inexperienced drivers — the “greens” — often don’t expect but need to know. I came to appreciate the cool of the lecture room as Saturday progressed, and it was a place to escape the constant din of barely muffled cars whining, zooming on the track beyond the long “pit” where paddocks line up.

Outside, asphalt heated in the sun, even though the air was temperate. Cars fitted with soft-treaded tires deposited rubber trails, especially where they gripped tracks in acceleration, braking, and the sideways pressures of pitched turns. Together, the sun loosened asphalt tars and the tires invisibly laid new trails and subtly reconfigured the track with slickness without moving its apparent path so much as a centimeter.

Learning “The Line”

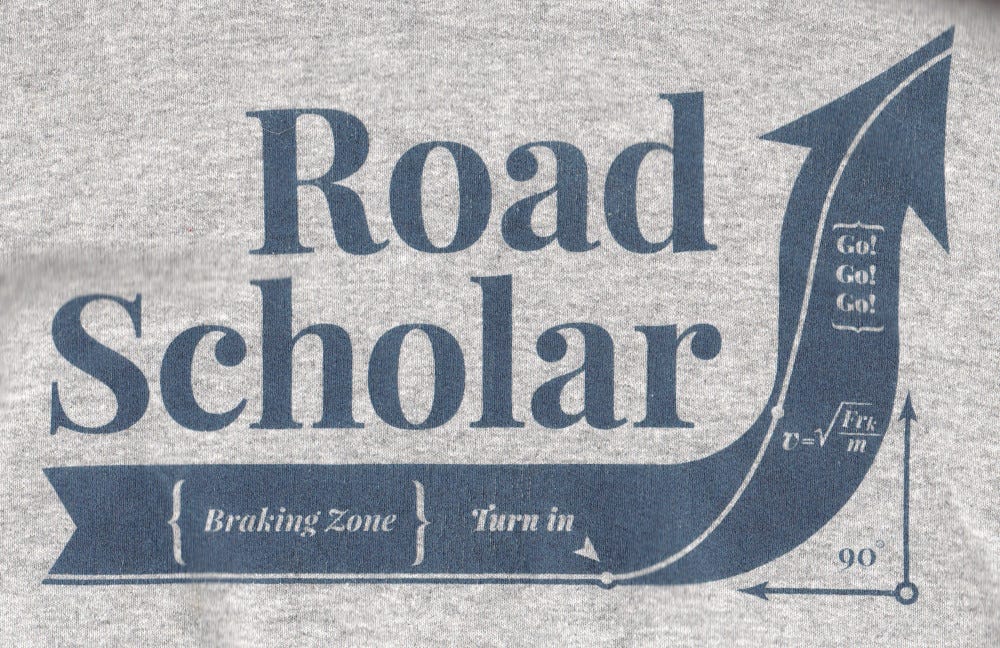

My morning sweatshirt was appropriate race driving attire, especially for a green learner like me. Labeled with the words “Road Scholar” it played with academic nerdiness; below those words a curving navy blue arrow appears, annotated with curly-bracketed directions, a couple of dots, and even a formula. It’s a map of a track, and the narrow line represents where you drive — The Line.

To look at the sweatshirt version of The Line reveals how it makes sense. The Line loosens curves by using the entire width of the track, and it indicates to some extent where you slow and where you speed up. It shows you where the “apex” of a curve sits, and the sweatshirt version of The Line even gives you a formula — one that I easily ignored while driving. And my disregard, I think, wasn’t just an attribute of being “green.”

My driving may be governed in some fashion by mathematics and physics, but to drive is also to feel. And in feeling, to take in and use much more than trajectories, velocities, and lines imagined on pavement. The feeling embodies not only the math but extends the body — my body — so that somehow the boundaries of machine and human body blur.

To drive The Line, literally and metaphorically, is to put your body on The Line.

To make this ambiguity of sensation even more ambiguous, The Line changes its surface with a rhythm reflecting the undulations of temperature or the whims of clouds and sun. Knowing where The Line should run only partly matters; the surface resistance (or its lack) also dictates how you learn The Line.

Learning the hot and slippery Line

Claude, my genial but demanding driving instructor, sat in the passenger seat. Really, our “seats” resembled lightly padded scoops, our bodies stuffed and secured in the tight embrace of five-point restraints, a sort of over-enthusiastic seat belt. Beneath sweaty helmets, Claude and I were connected by earphones and mics that just barely delivered our voices above the din of the track. My son’s old BMW E30 was our craft, which he had ruthlessly stripped of everything but the necessary. The few additions (mainly a roll cage and emergency shut-off switch) made us safer but not more comfortable.

In the afternoon, I raced full throttle past the observation deck and the line of paddocks in the pit. It was hot. It was loud. It felt good.

The approach to turn number one, “Horseshoe,” is straight, and signs on the left count down the distance to the turn. The idea is to go as fast as you can before hitting the brakes so that you can manage the turn. If you approach too fast, you swing out too far and end up braking even more to maintain control of the car (or you just run off the track). Drive too slow and you might manage the turn at a sedate pace but lose time to your pokey speed. The Goldilocks pace — not too fast and not too slow — means keeping to The Line but managing the forces of gravity and adhesion of the asphalt at a speed that’s at the edge of control.

For me, gravity stayed the same on “Horseshoe.” Adhesion did not.

I learned that three quarters of the way through the turn. I could show you exactly where I felt the tires slip ever so subtly and then more urgently.

“Whoa!” I broadcast to Claude’s ears.

Claude may have stiffened a bit in his seat.

Without thought and, strangely, without a sense of the difference between my human body and the steel and rubber of the old E30, I turned into the skid. The car quivered and righted itself. We avoided falling into a spin and ended up wiggling a bit as we moved forward on the track.

“Go! Go! Go!” Claude yelled, probably because he worried that I’d lose composure and slow to a grandfatherly pace.

That lesson taught by slippery tarmac lasted, oh, five seconds at the most.

It taught something of the cunning of The Line, which masquerades under an apparent, even mathematical, sameness. Same Line, every time, mapped securely on dry paper, a weak representative of the real thing with its tar smell, tire smoke, exhaust, and flag signals. Learning The Line is different from mastering it. That demands matters well beyond the reach of cartography and formulae — which my sweatshirt represented quite well — into matters of sensation and, in the case of my near tragedy at Horseshoe, unthinking competence and reaction. And luck.

You get that from driving and, in the case of my encounter, some experience driving on ice.

Another thing came with an encounter like mine on Horseshoe. I recently started reading Why We Drive by Matthew Crawford, and, briefly in, I ran into a paragraph that resonated:

A few years ago, I was loaned a brand-new Ducati by the good people at Popular Mechanics…. I took it on the canyon road that leads up to the Mount Wilson Observatory outside Los Angeles. At one point, my front tire hit a patch of sand just as I was apexing a blind curve, with my head about three feet from the rock face on my inside. The front tire slid maybe a foot, my inside boot dragged. Then the bike gripped, sorted itself, and kept going, finishing the turn upright. It was one of those episodes — a little glimpse of mayhem — where, if you come through it, you feel like you can stand a little taller afterward. “To dare, to take risks, to bear uncertainty, to endure tension — these are the essence of the play spirit,” Johan Huizinga writes.

The old E30 I drove was no new Ducati, and the danger I faced was paltry in comparison to Crawford’s. But the “little glimpse of mayhem” applies.

Teaching and The Line

I’ve thought about my role as a seminar leader and the ways that I’ve shaped an experience for students. I’ve mapped out a track in a syllabus and readings, but it’s in the interactions around the seminar table where the slippery stuff begins to require adjustments. We may threaten the peace of long confirmed views, unchallenged and unquestioned, that face slickened pathways.

The point is, of course, to confront the slippages and the treacheries of hard thinking. To come to new senses and new views without spinning out.

Got a comment?

RIP, Omar

Many of you wondered where the Friday post was. And here it is on Sunday evening.

The main reason, I guess, is that we had to put our dear little cat Omar down, which made things grind and chatter in daily life. He had been failing for weeks, and treatments couldn’t bolster him and pull him back to health. He was immunocompromised from kittenhood, and he lost his final fight.

He was a dear little cat, and now he rests out back by the fence in view of a nice field and next to his large dog friend Senna.

We’ll miss him.

And then, there’s Ophelia…

… who blew through the Carolinas yesterday dropping abundant rain and stirring up the leaves on the trees. She didn’t pulverize the leaves like her angrier sister Fran did years ago, but she managed to drop a couple of old dead trees that needed to come down anyway.

We lost power on Saturday. So much for ’stacking in the dark.

Tags: race, car, learning, vir, virginia international raceway, hpde, driving, omar, ophelia, wind, rain

So sorry to hear about Omar, Mark. What a sweet face. I’m glad you made out well during Ophelia, minus a day in the dark. As always, enjoy reading about the world of HPDE. That shirt is all kinds of amazing.

Thank you for sharing this, Mark. My condolences on Omar's passing.