The villainy of things

Some 99-year-old tools might scare you. Fantastical creatures I ran into while reading for a chapter I'm writing. And children working with tools.

I was reading Non-things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld by Byung-Chul Han (Bookshop.org) in my usual sniffing around topics that interest me. I’m in the midst of writing a chapter for a long-standing book project, and Han seemed to poke at ways that material life — especially the life of work — centered on “things” and, increasingly, “non-things,” by which he means (mostly) digital representations, “informatons,” and the objects, like smartphones, that present them. He’s not exactly crazy about the seemingly inexorable shift to digital and “information.”

At one point Han mentions Mickey Mouse, under the heading “The Villainy of Things”:

In the earlier episodes [of Mickey Mouse cartoons], things behave treacherously. They take on a life of their own, even a waywardness. They are unpredictable actors.... Doors, chairs, folding beds, or vehicles can at any time turn into dangerous objects and traps. Mechanical things are diabolical. There are constant crashes. The hero is exposed to the vagaries of things. They are a permanent source of frustration. The cartoons are entertaining to a large extent because of the villainy of things.

Related post:

It is easy to see the change in today’s Mickey Mouse on the Disney Channel. Things that the old Mickey faced have disappeared, and in their place are “obedient tools for solving problems.” Children learn “that there is nothing that cannot be done, that there is a quick solution, an app, for everything.” That’s a mistake, Han thinks, that signals an erosion of humanity not a triumph of technology.

I was intrigued by this villainy of things and so I dove into its rabbit hole. I discovered some wonderful, if also weirdly threatening, creatures.

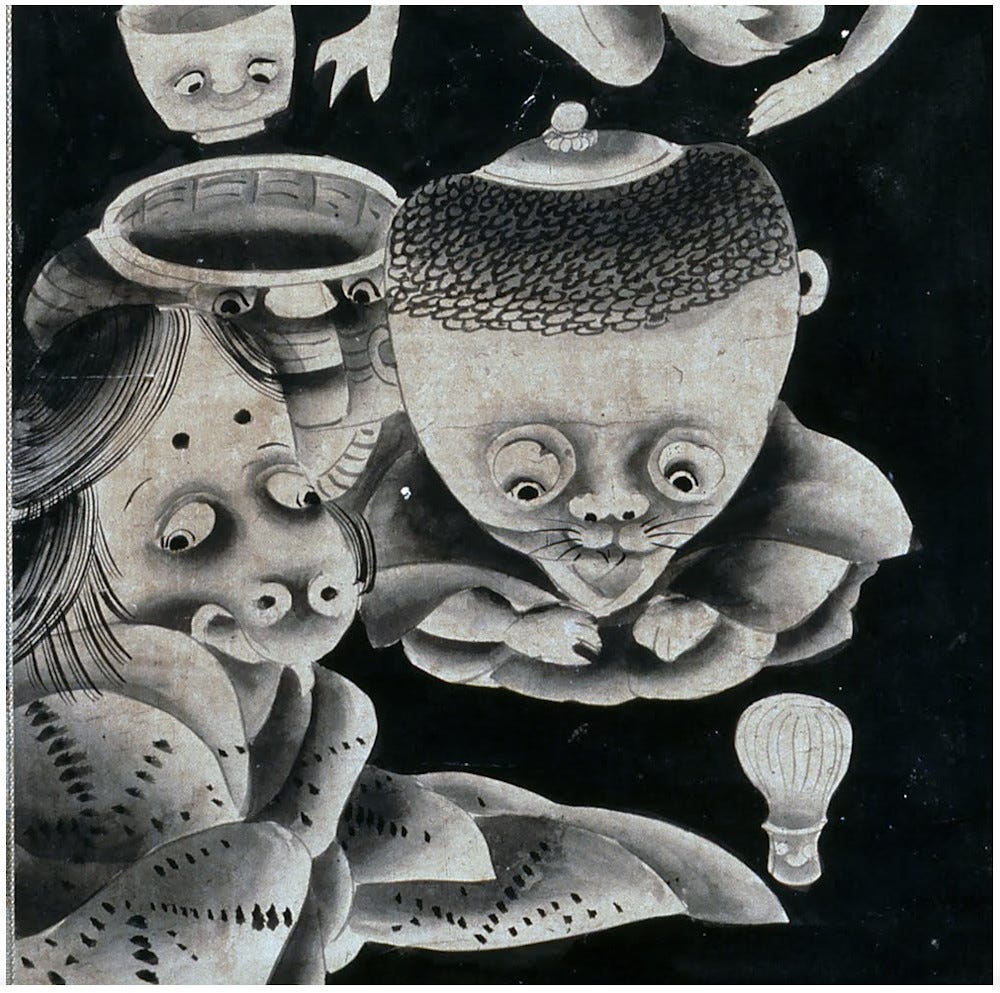

Tsukumogami, devious and contrary old things with souls

In medieval Japan, monks of Shingon Buddhism used humorous stories of old tools and utensils that had attained souls and become “sentient.” They took on fantastical and horrifying forms, often in shapes of animals, and they caused trouble and woe for humans. Stories of such “specters” probably existed before that time in folklore, so applying them to Buddhist teachings was attractive and easy. Scrolls tell the story of Tsukumogami ki 付喪神記 (The Record of Tool Specters) which date from the Edo Period (1603-1868).1 Full of drama and action, the story is a delight — especially before the monks get a hold of the story for didactic purposes.

The story begins with spring cleaning — the “usual custom of Sweeping Soot” — and old tools and utensils find themselves thrown out in streets and alleys. And they are very old things — the name tsukumogami in part derives from the Japanese number ninety-nine: “This event, called susuharai 煤払 (lit. “sweeping soot,” year-end house cleaning), is carried out to avoid misfortune caused by tsukumogami tool specters but a year short of a hundred.”

Of course, the old things took offense. They picked themselves up and bemoaned their fate: “We have faithfully served the houses as furniture and utensils for a long time,” they cried. “Instead of getting the reward that is our due, we are abandoned in the alleys to be kicked by oxen and horses. Insult has been added to injury, and this is the greatest insult of all! Whatever it takes, we should become specters and exact vengeance.”

After some debate and a fist-fight between a string of rosary beads (“Ichiren Novice”) and a club (“Rough John”), a scroll (“Professor Classical Chinese Literature”) suggests a plan: “Let us wait for the setsubun 節分 (the lunar New Year’s Eve), when yin and yang change their places and shapes are formed out of entities. At that time we must empty ourselves and leave our bodies to the hands of a creation god (zōkashin 造化神). Then we will surely become specters.”2

Naturally, the plan worked beautifully and ushered in what no doubt counts among the most extreme examples of the “villainy of things.”

The tsukumogami, now specters, settled near Mt. Funaoka, known primarily as a cemetery but near the capital city. And there they partied and, well, raised Hell:

From there, tsukumogami ranged in and out of the capital to avenge their grudges. As they took all kinds of humans and animals for food, people mourned terribly. But since specters are invisible, there was nothing that people could do but pray to the Buddhas and gods. Unlike the mortals who had cast them aside, the vengeful specters were having a great time celebrating and feasting — building a castle out of flesh and creating a blood fountain, dancing, drinking, and merrymaking.

“Extraordinary-looking divine boys” to the rescue!

A castle of flesh! A blood fountain! And besides that impiety! “They even boasted that celestial pleasures could not surpass theirs,” the story reads.

The tsukumogami did try to straighten up a bit. They built a “shrine of the Great Shape-Shifting God” to honor the forces that gave them their ensouled forms, and they at least maintained an outward expression of piety: “They chose a Shinto priest’s headgear for a priest, bells for shrine maidens, and wooden clappers for kagura performers, and they offered prayers every morning and observed rituals every evening.” But, finally, they were little more than evil and violent pirates. As the storyteller explained, “It is like that great thief, Dao Zhi 盜跖, who followed the five cardinal Confucian virtues.”

People had enough, and so did the Emperor, especially after the Prince Regent had a confrontation with the tsukumogami as they paraded their Great Shape-Shifting God down an avenue in the city. The Prince Regent was not amused. When “he glared angrily at the specters,” a flame unexpectedly shot out from an amulet he had around his neck and the tsukumogami fled.

Then followed courtly exchanges, contemplation of imperial policy, religious ponderings and petitions, and probably some intrigue.

After much prayer and burnt incense, “the Emperor saw a brilliant light just above the palace. Inside the light were seven or eight extraordinary-looking armed divine boys (gohō dōji 護法童子). Some had swords and others had bejeweled staffs — they all flew northwards. The emperor was moved to tears, understanding that the attendants of two myōō 明 王 (Vidyārāja) had appeared to conquer the evil specters.”

The divine boys quickly routed the miscreants and presented an offer they could not refuse: “If you forswear evil, promise not to harm humans, and revere the Three Treasures of Buddhism and seek buddhahood, we will spare your lives.” And then, just to nail home the stakes, they added: “Otherwise, you shall all perish.”

Thereafter, the tsukumogami indeed reformed themselves. They shaved their heads, donned monk’s garb, retreated to the wilderness for contemplation, and practiced rituals and prayers so well that they achieved buddhahood.

Remember the rosary named Ichiren Novice, the poor guy beaten up by the club Rough John? Well, he angrily fled after the fight, but he continued to follow the precepts of Buddhism. He became Holy Ichiren — no longer a novice — and was adopted by the now penitent tsukumogami as their priest.

Villainy, yes, but also villainy overcome with the sweetness of enlightenment.

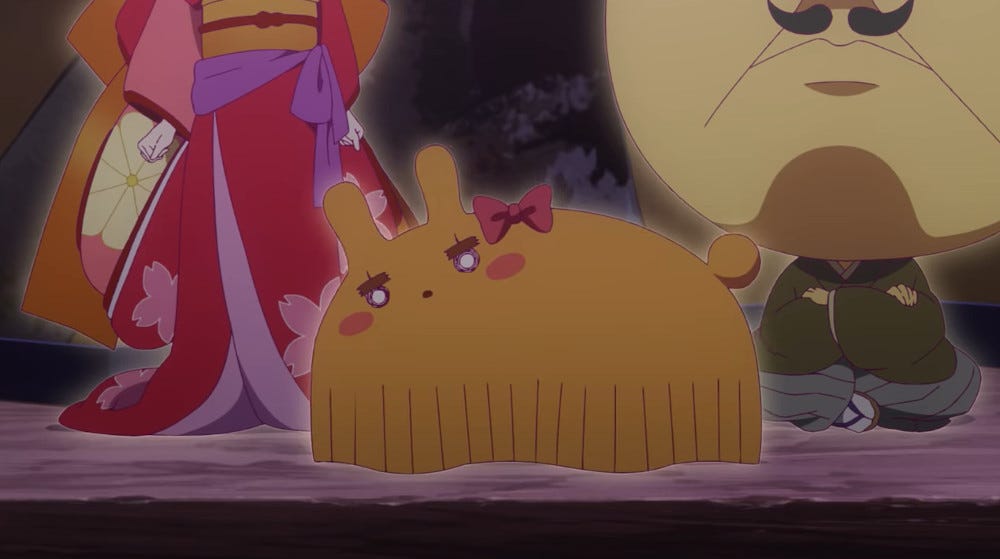

As I read through the translation of Tsukumogami ki, I couldn’t help but think how it could be made into an entertaining, if a bit gory, movie. It was hardly a novel idea. Tsukumogami have made their way into other stories since the Edo Period, when the tool specters were very widely known. The specters have also become a bit less threatening. Since the mid-twentieth century, tsukumogami have made their way into books and movies and video games (Super Mario!). In 2018, they were the stars of a short lived anime television series in Japan.3

The frustration of tools: surmountable villainy and a kind of knowledge

It’s an extreme example, this tale of common tools, furniture, and utensils like umbrellas, brushes, futons, lanterns, and pots getting souls after ninety-nine years of service — and then becoming evil to exact revenge for being tossed away or neglected. However, the story of tsukumogami resonates with Byung-Chul Han’s “villainy of things.” (Actually, I’m surprised he didn’t cite the Korean dokkabei, which also spring from common tools and are just as mean-spirited.)

Things resist us. They are clearly external to us — part of a world of things. Important to Han’s thought, they instruct us about Otherness. And, if I can go out on a limb a bit, they teach us and extend our understanding in ways that might allow us to ascribe “sentience” to them. (I know . . . a projected “sentience,” at best.)

I watched my children come to terms with tools in the garage as they worked on projects and cars. Dexterity is learned behavior, I came to learn. The ease of grasping, positioning, and manipulating a pair of pliers does not magically nestle into human hands at birth.

Things have minds of their own.

Tools instruct through being used. The familiarity of hand and tool grows somewhat mysteriously by feel rather than by some sort of cognitive understanding. The body learns, the tool teaches, and part of the lesson contains the matters of things, the stubborn, yet plastic, durable material world. The tool teaches special forms of interaction with things.

When my eldest child first wielded a wrench, I had to restrain myself from guiding his hand with mine. To do so meant interrupting the tool’s instruction, which required only a child’s clumsy touch and willingness to endure a scrape for the sake of tool-education. My middle child’s education at the hand of tools was gentler, it seemed, perhaps because he often played with them and grew with them. Always a car tinkerer, he became an automotive technician, race car builder, and eventually a mechanical engineer. My youngest, though no persistent haunt in the garage, felt a certain obligation, I think, to see what tools could teach and found a home in working wood, which involves its own set of specialized tools.

It’s not just that one learns how to work a tool with some measure of grace. The tool extends as well. Through the wrench, I sense the bolt and feel its connection to the metal surrounding it. I can tell when rust has seized it or when an old bolt threatens to break. Of course, the tool enhances my grip, but it also stretches my sense of the things it touches. That touch unscrambles the designs of things, uncovering otherwise hidden physics or the limitations of angles and spaces — clues that unfold to show how objects were assembled and how they are best taken apart.

After over a decade of working on cars, my younger son went back to college to pick up an engineering degree. He noticed that the school of tools set him apart from other students, many who “struggle with pliers,” as he told me. Machines in books can be learned, but machines touched with tools teach lessons more deeply.

The tool shapes and conveys force, of course, but it also communicates a kind of intelligence of things. The body learns to attend to that and directs the mind.

Now, I realize that talking of tools and things in such a way comes close to ascribing a certain intelligence and even a willfulness to objects. I shy from going that far, but I am willing to blur the edges of our human consciousness and the bodily boundaries of sense and sense-making.

I’m not the first one to do that. I’m certainly not the most imaginative, either. The stories of the tsukumogami take the idea farther and more creatively.

Got a comment?

Tags: thing, non-thing, tool, hand, craft, work, skill, labor, ensouled things, otherness, learning

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

By the way, Han’s prose is a little odd. In Germany, I guess he’s been called a bumper-sticker philosopher, in part because of his short sentences. Han believes that we flourish in a world of things, but we are increasingly surrounded by “non-things.” Han, Byung-Chul. Non-Things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld. Translated by Daniel Steuer. English edition. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2022.

Reider’s translation is readable and fun, and her article on the story explains the manuscript variants and provides a good introduction and interpretation of the story. Reider, Noriko T. “Tsukumogami Ki and the Medieval Illustration of Shingon Truth.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36, no. 2 (2009): 231–57, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40660967; and Reider, Noriko T., trans. “Tsukumogami Ki 付喪神記 (The Record of Tool Specters).” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36, no. 2 (2009): online only: 1-19, https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/journal/6/issue/179/article/1275

“Tsukumogami.” Japan Box. Accessed December 28, 2023. https://thejapanbox.com/blogs/japanese-mythology/tsukumogami.

Cock-Starkey, Claire. “11 Miniature Mischief-Makers From World Folklore.” Mental Floss, May 12, 2016. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/79913/11-miniature-mischief-makers-world-folklore.

Tsukumogami Kashimasu (We Rent Tsukumogami). Television series, July 23, 2018-October 15, 2018. https://myanimelist.net/anime/36654/Tsukumogami_Kashimasu.

“Throughout the year, temples across Japan hold a “ningyo kuyo” (人形供養), a funeral ritual for unwanted dolls — especially traditional dolls. Held in both Buddhist and Shinto temples alike, the ceremony is a spiritual send off to thank dolls for their service and properly put them to rest.” Greene, Heather. “Japanese Temples Are Holding Funerals For Unwanted Dolls.” Religion Unplugged, November 5, 2021. https://religionunplugged.com/news/2021/11/5/japanese-temples-are-holding-funerals-for-unwanted-dolls.

A good translation is available online: Reider, Noriko T., trans. “Tsukumogami Ki 付喪神記 (The Record of Tool Specters).” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36, no. 2 (2009): online only: 1-19, https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/journal/6/issue/179/article/1275

I took special delight in the cavalier response of the tsukumogami to Professor Classical Chinese Literature: “Everyone wrote down what the professor said on pieces of cloth and left.” The fate of the classical literature professor!

The television series is an anime: “We Rent Tsukumogami” which aired in 2018. The premise of the series is quite delightful: “The series is set during the Edo period, in the Fukagawa ward of old Edo (present-day Tokyo). Because the area is prone to fire and flooding, residents rent everyday items like pots, futons, and clothing from shops instead of purchasing them, so as not to impede them when they flee. Obeni and Seiji, an older sister and younger brother, run one such rental shop called Izumoya. However, mixed in with their inventory are tsukumogami, objects that have turned into spirits after a hundred years of existence. The siblings sometimes lend these sentient items to customers. Both Obeni and Seiji can see and talk to these spirits, and other tsukumogami often come to the store after hearing of the famed siblings.”

TVアニメ『つくもがみ貸します』PV第2弾, 2018.

An informative article in Japan Box discusses modern adaptations of tsukumogami, including references in work done outside of Japan (https://thejapanbox.com/blogs/japanese-mythology/tsukumogami). Even Super Mario has the little beasts: “A well-known presentation of various tsukumogami in computer games can be found in the Game Boy game Super Mario Land 2. There, entire levels (for example, Pumpkin Zone) are dedicated to various Yōkai and tsukumogami. Tsukumogami that ambush the protagonist Mario there are the Chōchin-obake [‘an ensouled Chōchin lantern’] and the Kasa-obake [‘a possessed paper umbrella with one leg, two arms, one eye, and a long tongue’].”

very interesting, and kudos to you for delving into this topic. I find Japanese culture both intriguing and impenetrable. I ahve grown to like Manga and anime too.