“This is a test of the Emergency Handwriting System”

Handwriting (you know, using hands?) enriches human expression. A side-effect of a New Year's resolution....

In February, after a month-long consideration, I set my New Year’s resolutions into a five-by-five grid. I made a BINGO card—twenty-four resolutions plus the FREE space. It was my attempt to gamify the whole tired resolution process that I’ve failed at so well. Surprisingly the trick seems to have worked, at least partially.

One of my BINGO New Year’s resolutions was to write more letters. In fact, that was the first thing I thought of when I compiled my list and so it occupies under the “B”, one (to use BINGO-caller’s lingo). Activities have implications, I told myself, and “doing stuff teaches habits that transcend the things you do. Sure, some of my items look to-do-ish, but they can also lead to virtues.” That message headed up a post entitled “The Fate of Letters,” and I now wonder whether there was some subtle prognostication in the works.

Letter writing has begun to teach me some things.

“One thing about your letter,” someone told me “it’s so hard to read your handwriting.” He was referring to my handwritten note to North Carolina’s US Senator Thom Tillis, written as the new administration was winding up the wrecking ball and Congress sat in the bleachers, silently watching. “In the Senator’s office,” he continued, “they’d not bother to read it, I’m afraid.” (I was glad to have provided my readers a transcript.) And it is true, my handwriting is bad but not illegible. Scores of students have trudged through my comments squeezed into margins and in closing notes on their papers. Only occasionally have I had to “translate.”

Three of my recent letter recipients have commented (not exactly complained) about my writing, too. One, a physician, admitted his handwriting was about as scrawly and awful as mine. Another commented, “It was a pleasure to decipher your handwriting—not as bad as mine but a challenge nonetheless.” Even in a bewilderment of inky swirls and stabs, some readers were able to find a certain pleasure.

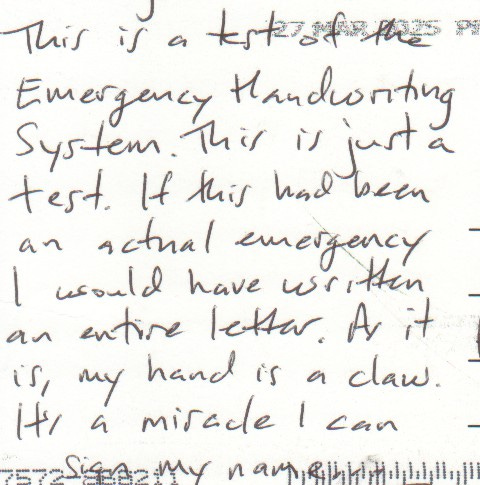

Another recipient sent me a postcard response, which he labelled a “test of the Emergency Handwriting System.”

There may be a truth hiding here: Writers may feel their handwriting is “worse than yours,” but it’s not. The varieties of “bad” are plenteous, but nearly everyone’s handwriting is legible, mostly. And mostly is good enough, mostly.

I did have a crisis of handwriting confidence at one point during my recent letter writing. I decided to “type one out,” and I even thought I might fish my old, light blue, German-keyboarded (“QWERTZ”) portable typewriter from the attic. But I settled for LibreOffice and American Typewriter font.

That momentary lapse did teach me a lesson: Handwriting itself expresses, and its subtly expressive twists nudge prose. The end product of my keyboarded missive was legible, but bland. The writing, it seemed, was as flat as the paper.

Handwriting itself is a technology, of course, and one that has already remade the world. Letter writing appeals to me in part because it pushes an ancient means of messaging into a communications world that is, for better or worse, governed by techbro’s “platforms”—an immaterial “place” where human messages are distilled into data which is then squeezed for profit. Letter writing on paper relies on humbler technologies and, I think, clearer communitarian aims: The envelope contains the purpose of the postal service; Lord knows there’s no profit in it, except as a material bond that draws together individual people scattered about. The US Postal Service is in the US Constitution, too, under Article I: Congress has power “to establish Post Offices and post Roads.”

Besides that, when I handwrite a letter, my hand moves to draw a thought for a specific person. A person who may live thousands of miles away soon (or maybe soon-ish) will grasp the same paper and decipher a personal message from my distinctive and messy hand.

With a letter I have an audience of exactly one. How freeing that is for a writer!

Mr. Palmer (among others) shaped letters up

Bob Mondello discovered 43 letters saved by his mother when she was nineteen-year-old Omah Perino who danced with American GIs at Red Cross social clubs in Rome. Those dancing GIs wrote the letters in the closing days of World War II, and they were all clearly smitten by Mondello’s mom. Before getting to the words, Mondello, his sister, and her family noted the handwriting of the young men: “By today’s standards, these Greatest Generation guys were practically calligraphers — swirling cursive script, lines straight even on unruled paper. Beautiful penmanship, without necessarily writing skills to match.”

If today’s hand is ugly, people exactingly steered the pen generations ago for clear business reasons. The writers of Omah Perino’s letter cache probably learned writing using “the Palmer Method,” one of a series of quite systematic handwriting methods that established the “fonts” that appeared from people’s fountain pens. The Palmer Method is still sometimes used for teaching “penmanship.”1 Communications have always required clear and efficient writing, but efficiency was not the hallmark of the ornamental and difficult Spencerian hand that predominated before Palmer’s Method caught on in the early years of the last century. Austin Palmer taught the method bearing his name at the Samuel A. Goodyear’s Business School, and his textbook, The Palmer Method of Business Writing, was a best-seller. Today, we might find it baffling, but in 1912 alone, over a million copies of Palmer’s book were sold.

It’s important to remember that, before widespread use of typewriters or computer keyboards, handwriting pointedly served business interests. Indeed, the connection of business and writing is as old as writing itself. Among the first uses of Sumerian cuneiform tablets about four thousand years ago was to track rations and grain and livestock inventory. Spencerian script of the 1800s was pleasingly florid and hard to master; Palmer’s hand was quicker and simpler and better suited to faster twentieth-century business.

As standardized as they are, the methods of penmanship still leaked individual quirks, distinguishing someone’s scrawlings from the rest. From the 1940s into the 1970s, such individuality in scripts especially found its way into psychology and studies of human well-being. Researchers tried to link habits of the pen to “personality,” behavior, and psychological affliction, but their efforts never pushed “graphology” into the world of bona fide science. Articles on handwriting and behavior published at the time show a variety of interests: in 1955, two Italian researchers published an article comparing handwriting of Alpine mountain climbers with normal people. How does space flight affect handwriting? Six Russian researchers published their report on the question in 1965. In early 1968, A. Legrün published a two-part report on “The handwriting of ‘easy’ girls” (“Schriften ‘leichter’ Schulmädchen”) Five years before these articles appeared Legrün had investigated the handwriting of juvenile murderers. In an an article from 1948 in the Journal of Insurance Medicine actuaries wondered if handwriting could predict mortality. Such topics, which sought to draw clear and scientifically sound lines between human behavior and their hand, have become less prevalent in research literature, it seems. Analysis of handwriting has become more of a “forensic” activity in current scientific literature, especially focused on determining the authenticity of documents. But the linkage of handwriting and human characteristics still attracts researchers’ attentions.2

Rich (and nonscientific) realities in the archive

Study of handwriting that strives for a scientific credibility, it seems to me, fails to clear that hurdle. But less scientific approaches can have merit. How many researchers succumb to the desire to follow the lines of handwritten documents and attempt to use them to draw a picture of the person who once held the pen? I’ve experienced some of the singular delights of work in archives where people seem present in their wordy artifacts, but I’ve not often used handwritten documents. Alan Jacobs recently reflected on a dive into archives, as he read letters of detective fiction writer and critic Dorothy L. Sayers, whose papers are preserved at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. Jacobs looks beyond the words to consider the shape of, well, the letters in her letters, and he readily admits that his interpretations are his own, not gussied up in a scientific garb.

Of Sayer’s youthful hand in letters to her parents, Jacobs writes, “Perhaps the rush of her life helps to explain the look of her letters to them, but one thing seems quite clear to me: the loose, flowing hand is associated not just with hurry but also with happiness…. When she is going through harder times, through romantic disappointments or vocational uncertainties or just plain poverty, her handwriting is neater, more uniform, more under control.” Contents of the letters align with the “flowing hand” or the neater, “more under control” hand, too. Jacobs sees the hand as a reflection of Sayers’ state of mind, and I think much of the power of archival research comes from this kind of engagement with documents. Jacobs’ “interpretations” are not merely impressionistic take-aways, not merely idiosyncratic personal opinions. They are informed judgments that enrich scholarship and express reality.

Jacobs ends his brief blog post with a personal reflection:

And I can’t help thinking … Almost all of my correspondence—sent and received—has been typed. It is therefore informationally poor, lacking in richness and density, in comparison to the correspondence of the writers I work on. (Though it should be said that letters typed on a typewriter have more character than those printed from a modern printer or having a digital existence only.) I suspect that if I had big folders of letters from friends I’d look through them fairly often; searching Gmail does not promise the same reward.

I agree. Handwritten letters share a richness and density that Gmail can never approach. Handwriting—pinched from that most human appendage, the hand—somehow manages to capture lived experience and set it on a page. As new technologies sloppily march on, we need to find such elements of humanity, exercise them, and preserve them.

This article appeared on 3 Quarks Daily on June 18, 2025.

Tags: correspondence, letters, handwriting, word processing

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Of course, letter lovers know to subscribe to Shaun Usher’s Letters of Note. “Nothing but history’s most interesting letters.”

Bob Modello’s reflections on the cache of his mother’s letters shows a new side to “Omah”—before she married Tony Modello and began her family. You can listen to this one, too: Mondello, Bob. “Discovering a Mom We Never Knew, in Letters She Saved from WWII Soldiers.” NPR, May 8, 2025, sec. History. https://www.npr.org/2025/05/08/nx-s1-5371628/bob-mondello-mother-world-war-ii.

Alan Jacobs short blog entry is worth reading. He includes pictures of the documents: Jacobs, Alan. “Handwritten Moods.” The Homebound Symphony, April 4, 2025. https://blog.ayjay.org/handwritten-moods/.

A medical school professor laments the passage of handwriting: Parslow, Graham R. “Commentary: Handwriting in the Digital Age.” Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 41, no. 6 (2013): 450–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20740.

Handwriting has become a small part of the culture wars waged in primary education, and not only in the ever contentious United States: Müller-Lancé, Kathrin. “Schule: Müssen Kinder noch Rechtschreibung lernen?” Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 25, 2024. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/schule-bildung-rechtschreibung-fehlerquotient-lux.45G4kuoPA9XW4TgKgux41R.

And, though unrelated to handwriting, a piece that might become useful in the United States: Kwon, Karen. “How to Protect Yourself during Protests.” Scientific American, June 26, 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-to-protect-yourself-during-protests/.

The Palmer Method supplanted the strict, florid, and quite difficult Spencerian Method, which many would recognized from old legal documents or business correspondence from the nineteenth century. The Spencerian Method was devised by Platt Rogers Spencer who was a business school teacher, like Austin Palmer. The methods of handwriting are surprisingly plentiful: Zaner-Bloser Method, D’Nealian Method, “Library Hand” (by Melvil Dewey and Thomas Edison), Barchowsky Fluent Handwriting (BFH), and no doubt many others. Those who have used old library card catalogues have probably seen well thumbed cards bearing Library Hand script. My own primary school writing instruction very likely used the Palmer Method, which was by the 1960s fading from use. I think it’s worth saying that my teachers failed to shore up my handwriting.

You can see the shifts of topics by looking through results from a PubMed search. From 1882 to June 12, 2025, PubMed reports 4,686 results, with nearly 3,000 of them appearing in the last 25 years. So, there is still quite an industry of handwriting analysis, and researchers continue to link handwriting with behavior and health. Of course, laments about physicians’ notoriously poor handwriting is practically a subgenre in the bunch.

My hand still hurts from that emergency handwriting test … I’m sticking with the keyboard.

Mark! Utterly fascinating post - just wow! I've been brainstorming my own post on handwriting for a little while now - very different to yours! - but it's going to be brewing for a little longer because I keep getting sidetracked. I came across an astonishing book called 'Noodle Words' - a lighthearted look at beautiful Chinese characters, and that twigged me to remembering my poor 7-year-old au pair kid in Germany having to learn 'Schreibschrift' straight off the bat, no messing around with printing or anything..... bless him, they only START school over there at 7, but it's absolutely in at the deep end with what looks at first glance to be flippin' COPPERPLATE lettering!

I love the pic of your writing. Looks pretty great to me, Mark!