A business professor and a commie provide an intriguing path to trace

Will AI behave like earlier automation? What affect will AI have on skill requirements? They're open questions.

I was putting this post together when I got another interesting article from

called “Is it time for the Revenge of the Normies?” Smith argues that new technology could benefit what Smith called “the normies” — the middle class who work hard and competently but who don’t stand out as tech-nerds have in the past decades. Indeed, the gap between “the nerds” and the “the normies” grew in his lifetime, as the manufacturing economy gave way to the knowledge economy based on industries like computers, biotechnology, and finance. “Bespectacled programmers and math nerds became our richest men,” he correctly points out, leaving the factory managers and owners behind.We’ve become used to the idea that technology brings inequality, by delivering outsized benefits to the 20% of society who are smart and educated enough to take full advantage of it. It’s gotten to the point where we tacitly assume that this is just what technology does, period, so that when a new technology like generative AI comes along, people leap to predict that economic inequality will widen as a result of a new digital divide.

Smith doesn’t think the unhappily more lopsided fate is inevitable, though. He writes, “I think it’s possible that the wave of new technologies now arriving in our economy will decrease much of the skills gap that opened up in the decades since 1980.” Smith hopes that the decrease in the skills gap translates into less inequality. He refers to himself as a techno-optimist, and I hope he’s right.

I’ve been looking at the relationship of technology and skills, too, though through a different lens than Smith. Less economic, a bit more, well, experiential. The question for me has been about qualities of work, the contexts of work — in short, I’m focusing a bit more of the inner life of workers. Skill, of course, is central to our experience of work — both personally and economically.

Skill relates humanity to production, to the execution of tasks; and skill translates into economic value.

I wrote about the relationship of technology and skill about a year ago:

Boston bakers, more and less

Read time: about 12 minutes (not counting the seven-minute baking video!) This week: Bread is basic, and how we make it has changed. What does it mean to bake? A simple story revealing a facet of our complex relationships with technology. And a twenty-five year-old observation about working from home. Next week: I see students from the past.

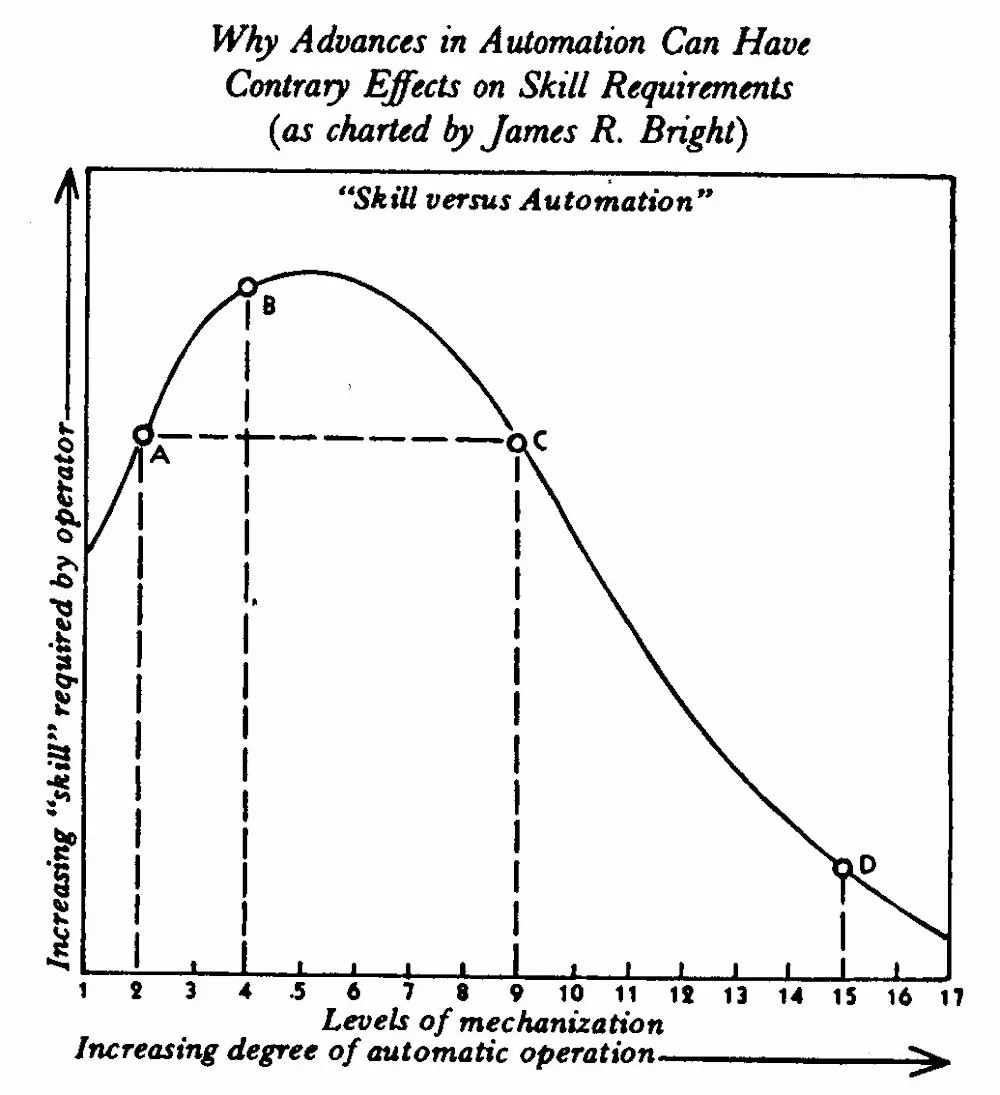

A figure that I included in the “Boston bakers” piece intrigues me. I found it in Harry Braverman’s Labor and Monopoly Capital, which topped the list of The Wall Street Journal’s important books on “working.” By including it in the list, the newspaper of American capitalism highly recommended a book by a thorough-going communist published by an unapologetically communist publisher. Braverman included a graph, based on articles by James R. Bright, that shows the diminishment of worker skills with the increase in the capability of automation. Here’s what the graph looks like:

Follow the curve and you’ll see that skill levels briefly increase as machines become more “automatic” but then drop off dramatically to a point well below skill levels that were required before the introduction of automation. For all practical purposes, mature automation — Bright’s “level 17” of his “levels of mechanization” — turns human involvement into “unskilled labor.”

Much of James R. Bright’s work on the effects of automation on labor, skill, and management appeared in the 1950s in Harvard Business Review — another not exactly pro-communist publication though probably not as stridently capitalist as The Wall Street Journal can be. I tracked down three of his articles, all published in HBR in the 1950s and all related to automation and skill requirements. I figured it would be interesting to see what Bright had to say and relate his message, if possible, to the noises we’re hearing today about AI and jobs.

But, as is often the case, what I found was interesting for other reasons as well. Bright highlighted a theme that animates much of the discussion about modern technology.

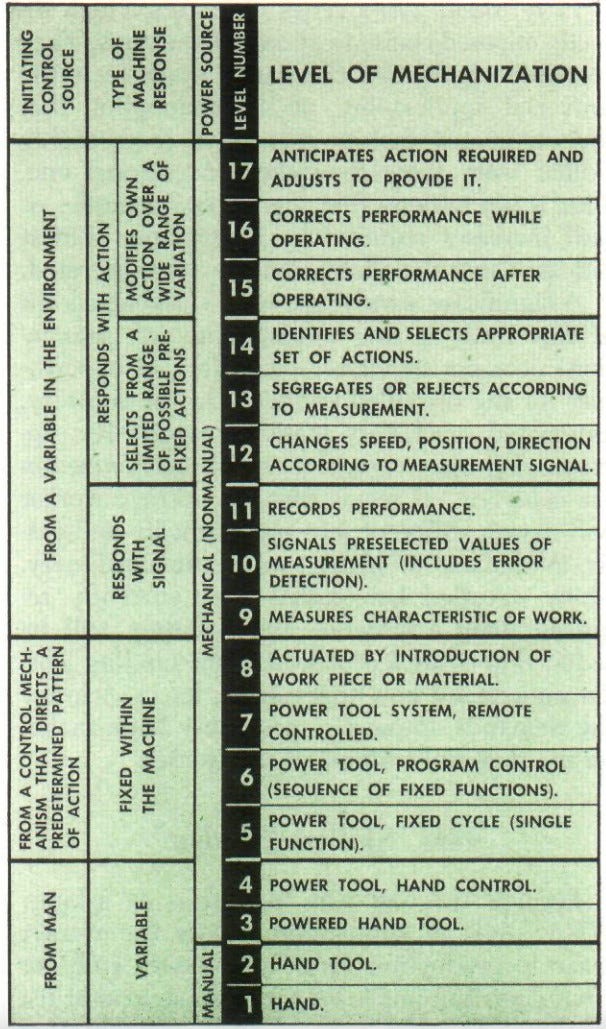

See if you can identify the word that I found intriguing in this brief excerpt from the article in which Bright establishes “levels of mechanization,” from human hand (levels 1-2) to automation that “anticipates required performance and adjusts accordingly” (levels 9-17):1

In passing to the fifth level of mechanization — the fixed-cycle power tool — it is apparent that we have not only mechanized the guidance of the tool, but we have also mechanized its application in the time dimension. Other than starting and stopping the machine, or possibly modifying its speed, the tool is completely mechanically controlled. Level 6 is nothing but a more advanced form of Level 5. Level 7 has remote control, often applied to the next three lower levels; I insert it at this point because it enables the centralization of control of a number of machines. Finally, we have the machine controlled by introduction of the work piece.

At the ninth level of mechanization a new force is becoming predominant in the control action. The environment, the product, or the nature of the operation itself at given moments becomes the initiating element of the system. Control here is no longer mechanical, fixed, or rigid; rather, it is variable according to performance. The control indication may be prior to, or during, or after the production act has been performed. Thus we see the basis evolving for still higher levels of mechanization. The principal importance — the principal distinction — at this point is that control itself is becoming a variable.

The word control intrigued me.

Control and its cognates appear eight times in the two paragraphs, and the last sentence tells us that, as the level of mechanization increase, “the principal distinction [of the levels] … is that control itself is becoming a variable.” As such, the powers of control — and isn’t control itself a telling signal of power? — move from human worker to the machine. Bright notes that control also becomes “the basis evolving for still higher levels of mechanization.”

Automation also shifted the tenor of work, established delineations and definition of work roles, and skills required — all of which centered on control that moved from human abilities to autonomous machine or was centralized for (often remote) management.

Will today’s AI automation shift levels of skill like what Bright observed in the 1950s?

In the 1950s, Bright asked, “In what way does machinery supplement man's muscles, his mental processes, his judgment, and his degree of control?” From that question, he developed his levels of mechanization that focused on automation of manufacturing, and as such he defined his levels to reflect the world of factories and production plants. Writing about a quarter century later, Braverman follows Bright’s focus, though not without exploring changes that “information processing” was beginning to impose on office work. For both Bright and Braverman, automation meant higher productivity — whether in metal widgets or data entry punch-cards — and diminishing requirements of skills.

Noah Smith’s article summarizes five recent articles2 that begin to explore how ChatGPT influences skill, though the articles primarily focus on productivity — an outcome of exercised skills (with or without automation). The studies focus not on manufacturing but on the “knowledge industry,” the domains of the “nerds”: coding, writing, test-taking. “Muscles” may not apply, but Bright’s question can be restated: “In what way does ChatGPT supplement human mental processes, judgment, and degrees of control?” And yet, the term “supplement” troubles me, because it suggests development or extension of ability. What might actually be taking place is more like a transfer or even a replacement.

What’s at stake is not only the automation of the creation of tangible and useable goods. It’s also a remaking of internal, personal human capability — the way that we function as human beings and even the ways we define ourselves. To be human is, in large part, to work and to think. Work and thinking measure up in ways other than economic productivity.

Smith’s summaries of the five articles are on target, and I highly recommend reading his post. The emerging pattern in studies seems to be that ChatGPT and other generative AI models can shore up low human skill levels in analysis, “creativity,” and skills required for productive call-center case handling. Generally the results show a leveling of skill levels, with lower skilled workers performing better and progressing more quickly.

Among call center agents, for example, Brynjolfsson et al. “find that access to AI assistance increases the productivity of agents by 14 percent, as measured by the number of customer issues they are able to resolve per hour. In contrast to studies of prior waves of computerization, we find that these gains accrue disproportionately to less-experienced and lower-skill workers.” And intriguingly, they continue, “We argue that this occurs because ML systems work by capturing and disseminating the patterns of behavior that characterize the most productive agents.” Basically, the AI system “captured” responses from high-performing/highly skilled “agents” to shape and “disseminate” prompts for lower skilled participants in the study.

Peng et al. saw leveling up, too, in their work with computer programmers: “Our results suggest that less experienced programmers benefit more from Copilot [the AI product used in the study]. If this result persists in further studies, the productivity benefits for novice programmers and programmers of older age point to important possibilities for skill initiatives that support job transitions into software development.”

Choi and Schwarcz look at “AI assistance in legal analysis” and see the same kind of leveling but with an added dimension. The study design used multiple-choice questions and written essays, and University of Minnesota law students took exams twice: once with and once without AI assistance. Choi and Schwarcz found that AI helped students “dramatically” with multiple-choice questions but had “no effect on student grades in the essay components of the two exams.” Whereas Brynjolfsson et al. observed a leveling up of lower skills call-center agents, Choi and Schwarcz saw another (and worrisome) dynamic at work in leveling: “The worst-performing students benefited enormously from AI, with gains of approximately 45 percentile points. By contrast, the best-performing students received worse grades when given access to AI, experiencing declines of approximately 20 percentile points.”

They end up seeing real promise in AI for “lawyering,” too. Their findings

suggest that AI assistance might not be particularly useful on average in complex legal reasoning tasks (like essay-writing) that more closely resemble the difficult work of lawyering than multiple-choice questions. Finally, the fact that GPT-4 outperformed both humans and AI-assisted humans with optimal prompting suggests that AI might entirely remove humans from the loop for certain kinds of basic legal tasks.

Of course, those findings come from studies that used generative AI as it’s available to the researchers in the early 2020s.

Rethinking Bright’s graphs for AI automation?

James Bright worked through the 1950s to collect data and analyze it in order to examine the relationship of automation and skill. “How to Evaluate Automation” appeared in July 1955 and displayed what amounts to some early visualizations of observations of skills in whole production processes, like the “rubber mattress unit” or “cylinder block line.” With these he offered an “exhibit … suggesting the nature of mechanization in production” — a first draft,3 one can say, of the seventeen “levels of mechanization” that he published three years later with detailed analysis of skill levels required for each.

No doubt the work was tedious in the 1950s, and it was paper based, as the reproductions of worksheets in “How to Evaluate Automation” show. Doing a similar analysis today might be considerably easier due to “automation,” and it could be helpful as society navigates the kinds of changes that will almost certainly take place in work and in training and education as a result of generative AI applications.

I’d sure be interested to see this kind of work.

Of course, there are stumbling blocks that stand in the way. AI products like ChatGPT are largely opaque, because underlying technology is so complex and because business interests enshroud methods. Bright could watch the machines operate and see whole production processes first-hand. With AI, that is less likely the case, so trying to place AI devices on levels is a bit more difficult. Besides, advanced levels of AI automation are actually unavailable and speculative. With current AI applications, we’re looking at machines that sputter and burp out discards and frequently flawed widgets resembling ideas.

Got a comment?

Tags: skill, production, industry, work, labor, unskilled, automation, control, ai, llm, call center, legal analysis, writing, computer programming, coding

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. 25th anniversary ed. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998. [Alibris, Bookshop.org]

Here’s the list that puts Harry Braverman’s book on top. Crawford has studied the place of work in life and learning, and his most well known book is Shop Class as Soul Craft (2009). Crawford, Matthew B. “Five Best Books on Working.” Wall Street Journal, September 4, 2009, sec. Life & Style. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204731804574385214231355206.

The three 1950s-era articles by James Bright that I looked at: Bright, James R. “How to Evaluate Automation.” Harvard Business Review 33, no. 4 (August 1955): 101–11; “Thinking Ahead.” Harvard Business Review 33, no. 6 (December 1955): 27–166; and “Does Automation Raise Skill Requirements?” Harvard Business Review 36, no. 4 (August 1958): 85–98.

From the BBC, some lighter reading: Morris, Ben. “How Long until a Robot Is Doing Your Chores?” BBC News, August 28, 2023, sec. Business. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-66288309.

And a disturbing report about my Alma Mater, not AI related. There is a failure here somewhere, and it needs to be corrected. I hope Duke chooses to correct it using a method other than hiring another high-priced administrator to fart around. Leonhardt, David. “Why Does Duke Have So Few Low-Income Students?” The New York Times, September 7, 2023, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/09/07/magazine/duke-economic-diversity.html.

Bright’s “levels of mechanization” are very interesting and probably quite useful for classifying mechanical automation used for manufacturing. I’m not aware of a similar classification of AI-related automation, probably because of the relative novelty and mystery of AI implementations. In the 1950s, Bright had a few opportunities to look at machines that operated on his seventeen levels, but probably none functioning at the highest, most automated, level 17. With mechanical automation, components and their interactions are physical and, therefore, more easily understood. AI automation follows much more mysterious paths — “black boxes” is the term — and so characterization similar to Bright’s levels remains out-of-reach.

Here’s a nifty table showing his levels that appears on page 88 in Bright, James R. “Does Automation Raise Skill Requirements?” Harvard Business Review 36, no. 4 (August 1958): 85–98:

They are Brynjolfsson, Erik, Danielle Li, and Lindsey R. Raymond. “Generative AI at Work.” NBER Working Paper Series. Cambridge, MA, April 2023. Working Paper 31161. http://www.nber.org/papers/w31161; Noy, Shakked, and Whitney Zhang. “Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence.” Working Paper (not peer reviewed), March 2, 2023. https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Noy_Zhang_1.pdf; Peng, Sida, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Peter Cihon, and Mert Demirer. “The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot.” arXiv, February 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.06590; Choi, Jonathan H., and Daniel Schwarcz. “AI Assistance in Legal Analysis: An Empirical Study.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY, August 13, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4539836; and Doshi, Anil R., and Oliver Hauser. “Generative Artificial Intelligence Enhances Creativity.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY, August 8, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4535536.

The July 1955 article includes a narrative and relatively concrete description of the levels in an “appendix” on pages 108-111. Bright suggests that the levels were useful for his work but were still tentative: “Here is a more detailed explanation of the 17 levels I have identified. This particular breakdown cannot be defended too rigorously. Examples can be cited that would somewhat confound this or any other classification. Doubtless additional subdivisions could be defined. Furthermore, some of these levels may be inextricably tangled with much lower levels. Nevertheless, I have found the following to be fairly consistent and usable.”

this is the second discussion I have seen of Braverman in the context of GPT. As always your thoughts are very inciteful. For this technology to elevate the normies, college degree requirements, especially in C.S. or equivalent years of experience, for traditional nerd jobs will have to dramatically decrease. I worry that the big 3 clouds are going to leverage their data gravity advantage to basically have senior and junior nerd workers train the cloud provider models to replace those nerd job descriptions in 5 years, while also locking enterprises into one cloud in the process.

will do Mark. When do you send out the yearly 'O magnum mysterium'?