CES "booth babes" before 1967?

It's CES time. Organizers and attendees have argued about the ladies since 1967, sometimes just about their label. Their marketing services date back much longer.

A brief announcement, mainly for “Followers”

Beginning with this post, I’m adding something new for email subscribers.

In part, it’s my response to the growth of so-called “followers” on the Substack platform. My problem? I’ve yet to figure out what a “follower” actually is, at least as far as the people involved are concerned. I do see the benefit to Substack, Inc., since “following” binds people to the platform’s app. Yet I’m mystified by what “followers” get out of the deal (an endless scroll in their phone app’s “home”?). I’m less mystified by what newsletter writers get out of it, since that appears to be close to nothing.

So, with this post, email subscribers get a little more more, simply because they’ve let my writing into their inboxes, where I hope they get some enjoyment.

What will email subscribers get? I’m still figuring that out, but in general I plan to share more personal news and brief comments on my current reading and thinking. “Up close and (more) personal,” as the cliché goes and which just feels right. After all, isn’t that what email started out to be? The contents might be an expansion of the substance of the post that’s displayed on the newsletter website. I’ve even thought about including feature that would replace the popular quarterly “catch up” post with interesting links I’ve run across.

We’ll see.

So, if you’re tempted to fall into Substack, Inc’s “follower” mode, maybe a free subscription would be better for you and for the author of whichever newsletter it is. If you’re a “follower” of Technocomplex, and you’re also mystified by what that actually means, you can easily change that and end up with more:

The tech babes, now and then

“CES” is one of those acronyms that once stood for something, in this case the Consumer Electronic Show. It takes place every year in Las Vegas, and tech-oriented publications report on it extensively, usually with gah-gah responses to flashy CEO keynotes (this year’s Nvidia’s Jensen Huang) and the thousands of sometimes odd and miraculous doo-dads.

Over the years, I’ve noticed another recurring topic for articles about CES: “what’s to be done about ‘booth babes’?”1 Female attendants in the booths have been on display since CES first ran in 1967, and reporting about them almost always has had a conflicted, how-can-this-be-a-good-thing undertone.

Over a decade ago, Connie Guglielmo took CES to task about their handling of the babe situation, noting that CES leadership seemed more exercised about terminology than, well, female booth workers donning pasties, body paint in crucial places, or otherwise “provocative attire”: “I am offended by anyone calling anyone a ‘babe’ under any circumstances,” Guglielmo quoted Karen Chupka, senior vice president of International CES in 2013. “We’re in the year 2013 and it’s rude.… I just don’t assume that we should call any woman who is working a booth at the show a ‘babe.’ The word babe offends me and I’m offended by anyone who uses it.”

Their attire didn’t seem offensive to her, though. Chupka excused painted ladies in thongs that some reporters noted the year Guglielmo’s article appeared. It’s just “art,” Chupka claimed.

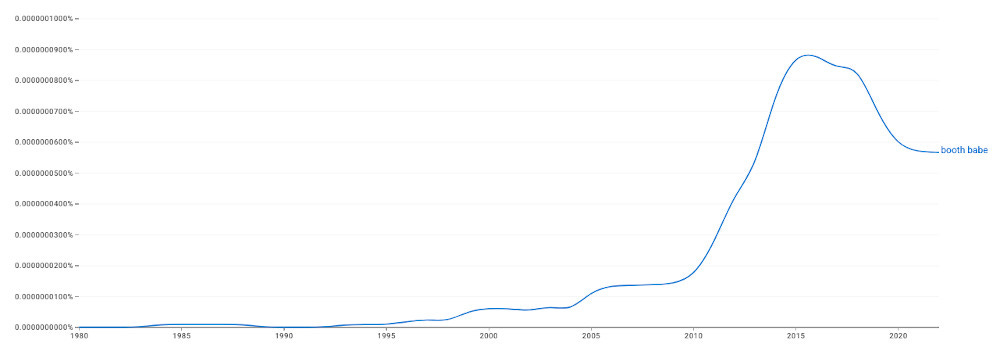

I had to check Google’s n-gram viewer to see how the “booth babe” term behaved over time.

The term seems to have waned a bit since 2015 and settled back to 2013 levels in 2022, which seems to me to mark no victory for Guglielmo or for others who protested the rank objectification happening at the shows.

ICYMI. Early automobile media with a weird twist

When “booth babes” were “show girls”

Reporting on CES and similar tech shows leaves the impression that technology shows think they invented the concept and its booth babe moniker. But the use of pretty young ladies at trade shows has gone on as long as people have been selling wares (to men, at least). That said, I do wonder whether the tactic has a special place in technology marketing or in the development of capitalist economies generally.

Using feminine charms to present certainly played a role in the marketing of the twentieth century’s leading technology: the automobile. The role was similar, but “booth babes” wasn’t the name.

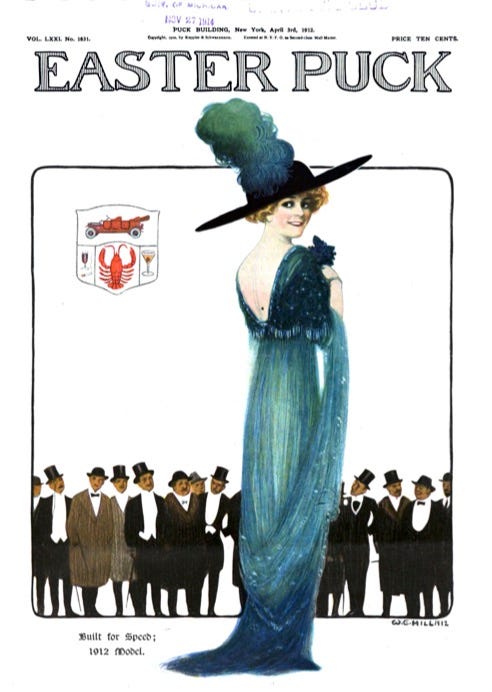

Hints of the association of women and cars are easy to pick out on the covers of old weeklies, and they clearly situate the ladies in relation with marketing and advertisement. In April 1912, American humor magazine Puck featured a sultry, feathered and sequined woman on its cover, her bare back showing as she glances over her right shoulder. In the background, a line-up of gentlemen ogle the woman, all in dress attire, some of them sporting a fancy cane or a monocle, all donning hats. The caption reads “Built for Speed; 1912 Model” and a crest hovering about the men shows a car, a lobster, and a cocktail glass. Model is a useful double entendre.

W. E. Hill’s “Easter Puck” cover transposes the language of automobile performance with the image of a beautiful woman. The woman’s suggestive pose and the car-referencing caption—built for speed—intertwine as well, making us wonder exactly which “model” provides the exhilaration or acceleration. The caption is a pivot for the sly purposes of the picture. If the words are elicited by the sight of the woman in azure and intended to label her, then the result is her objectification. The lady would be a product like a car, yet to be included on the club’s crest along with lobster, cocktail glasses, and car. And yet, if the caption mocks, the critique goes against the two-dimensional caricatures of men, the ones who thoughtlessly apply advertising words to a lovely lady. Satire and parody, the stuff of Puck for over forty years (1877-1918), are slippery things. The image from the 1912 “Easter Puck” allows some ambiguity, depending on how Puck readership would take it—as a piece that captures a woman as an object like a car, a sly stab at the superficiality and materialism of “men of culture” huddling below a parody crest, or perhaps even both.

The Puck cover points out the formation of habits that car shows more fully developed and exploited; the marketing races of cars and ladies had revved up by 1912, and certainly was running before that year. Two weeks after the 1912 New York show, Fred J. Wagner, known as a “daredevil racer” and the first “flagger” of the Indianapolis 500, rather defensively claimed that “selling motor cars is now dignified”—a statement that implicitly acknowledges that the car trade was undignified before. “Exhibitors used to think they could not sell cars unless they had three or four attractive young women to sit in their cars by the hour and gaze with a baby stare on their faces at the passing crowd,” he wrote with some relief in his New York Times column. “Theatrical ladies and good-looking girls were in demand for this purpose then.”

“EXHIBITORS USED TO THINK THEY COULD NOT SELL CARS UNLESS THEY HAD THREE OR FOUR ATTRACTIVE YOUNG WOMEN TO SIT IN THEIR CARS BY THE HOUR AND GAZE WITH A BABY STARE ON THEIR FACES AT THE PASSING CROWD.”

Not that the “theatrical ladies” were completely absent at the rash of car shows that were happening all over the country at the time. During the New York show in Madison Square Garden, the Times noted their attendance on “Society Night”: “There were stars in abundance, and any number of mere chorus and show girls,” the Times reported. “Miss Kitty Gordon, encased in huge white bearskin furs, walked about, and later was joined by Miss Jane Cowl and Miss Ethyl Jennings of ‘The Gamblers’ company.” The Times’ accounts of shows held at the Grand Central Palace and the Gardens read like society pages. Among the visitors: the Duke of Newcastle (“who delights in going about unheralded and unannounced”), several Vanderbilts, Mr. and Mrs. James B. Duke, Henry Ford (“who, though not an exhibitor, pronounced the show a success”), and other prominent members of New York society.

Although the then-new automobiles certainly had a technological substance that was very well represented at the shows, feminine charms of “show girls” radiated beside them. Henry Ford himself often trumpeted the technological marvels of the automobile and was, perhaps, a hold out in matters of alluring sales presentations. But he gave way after World War II, when marketing pressures and competition mounted.

Charming car ladies with their “baby stares” have persisted. I’ve been researching marketing strategies that Jaguar used in the 1960s and 1970s, and there is a certain continuity. Some fifty years after the Puck lady strode on the cover, the choreography of “theatrical ladies” and cars was complete and on full display at the March 1961 New York show. When Marilyn Hanold wrapped herself around the new 1961 Jaguar E-type at the US debut of the car at the New York show, her dress was cut similarly to that of the unnamed woman of the Easter Puck cover. Rather than glancing over her shoulder, Hanold was turned forward, without the plumed hat. In 1961, it likely would be out of place, anyway, and it would have detracted from other matters of her presentation.

Hanold at that time had credentials that qualified for the most exotic CES booth babe status. She graced the centerfold in Playboy as Playmate of the Month for June 1959 (OK for work and NSFW). She became an actress, too, on television (The Phil Silvers Show, Batman) and some B-movies (like, uh, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die2)

Will the market influence the booth babe’s fate?

The predominant market segment for cars in the first half of the twentieth century was male but became less so as the decades passed, to the point that women became the major U.S. car market segment in the last quarter of the century. Today, journalists writing about CES often note the predominantly male CES show-goers as well as the male dominance in “tech.” Their articles also feature quotations from business reps at CES who continue to see female sex appeal as a very effective draw to their booths.

But as the consumer tech gadget market evens out, maybe the babes will recede from view—or put on some clothes and share the stage with others. “If you can create a gadget that women like just as much as men (hello, iPhone) you have a hit on your hands,” MIT Technology Review editor Mat Honan wrote a decade ago. “So why would you want to do anything that might discourage women from showing up? (And it's abundantly clear that some women certainly are off-put by booth babes.)”

The booth babes have become less welcome at other consumer tech shows, and even the automobile industry is beginning to reframe the ways that women appear on stage with their cars. Mercedes-Benz has claimed to have retired the booth babe, and I’d bet that the marketing department is happy with the decision.

This video from BBDO Asia provides the reasons for the switch from “The Pretty” to a less gendered and more professional presenter:

Got a comment?

Tags: booth babe, ces, car, marketing, sex appeal, trade show, automobile show, technology, business

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

“We greet, welcome and invite people to enter the stand, even though we don’t know much about the company.” Rubio, Isabel. “Why Scantily Clad ‘Booth Babes’ Are Still a Draw at Tech Fairs like Computex.” EL PAÍS English, June 12, 2024. https://english.elpais.com/technology/2024-06-12/why-scantily-clad-booth-babes-are-still-a-draw-at-tech-fairs-like-computex.html.

The science (or at least the classification) of booth babes, by a booth babe. Don’t be misled, though: the classifications are “The Pure Eye Candy,” “The Lead Generator,” “The Product Specialist,” and “The Triple Threat”: The Booth Babe. “The Booth Babe Chronicles: Variations On A Booth Babe.” thetruthaboutcars.com, May 2, 2010. https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/2010/05/the-booth-babe-chronicles-variations-on-a-booth-babe/.

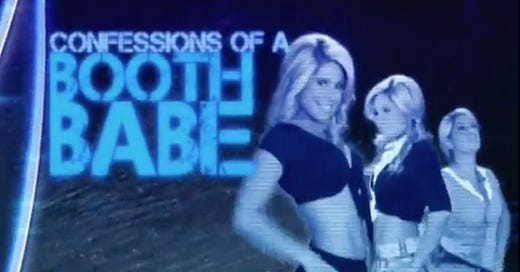

“There is nothing better than a hot girl in leather and heels holding swords and guns.” Huh? The video offers a view of a 2009 tech trade show. I wouldn’t watch this one at work, if I were you, but it does provide a broad view of the booth babe universe, including the business side—and the unsavory side of booth babe work. Sara Underwood (host). Confessions of a Booth Babe, 2009. G4 Special. http://archive.org/details/confessions.of.a.booth.babe.dsr.xvid-eclipse.

In case you like rummaging through really old newspapers (and have a New York Times subscription or a friendly library): Fred J. Wagner, “Selling Motor Cars Is Now Dignified: Auto Industry Is on Sound Business Basis—Los Angeles Preparing for Santa Monica Race.” New York Times, January 28, 1912, p. C18. “Crowds at Garden despite Weather: Many Theatrical Stars Attend Auto Show—Unique Methods of Showing Cars.” New York Times, January 9, 1912, p. 14. “Society Admires Motor-Car Models: Many Prominent Persons Attend the Garden Show—Boy Falls into Fountain.” New York Times, January 10, 1912, p. 15; “Many Purchases at Garden Show: Exhibitors Report Many Sales of Cars—Society Day Again Draws Big Crowd.” New York Times, January 12, 1912, p. 10.

But in 2025, maybe the booth babe issue has been solved? I haven’t seen the CES-related babe article this year yet. I have only seen one rather skimpy note on the tech websites.

Guess where the new body comes from. “A doctor experimenting with transplant techniques keeps his girlfriend's head alive when she is decapitated in a car crash, then goes hunting for a new body.”

Mark, have you learned nothing from the marketers you’ve studied? Surely you’d increase the numbers on this post if you included a bunch of pictures of booth babes, or perhaps had a list of the five hottest booth babes from CES. I’m just saying …

Seriously though, I used to spend a lot of time at cybersecurity conferences, with the annual RSA Conference in San Francisco the premier event of the year. Booth babes were common, and after two years of lamenting our low booth traffic (my company had a booth at the trade show) our CEO decided that he would hire some booth babes of our own, who stood there alongside our sales people and did their best to get the predominantly male crowd to stop and chat. I was embarrassed by it, but Steve (our CEO) insisted that it increased the “size of the funnel,” which was all he really cared about. Ah, commerce is so dirty!