"Routine miracle"

A sonnet sequence with copious detail on its production and revision for the curious

The chickens hovered at the edges of their pen when I walked out back. I greeted them and decided they needed some scratch — “chicken candy,” good for cold nights, maybe, but otherwise a snack more luscious than regular old pellets.

Out of habit, I opened the door above nest boxes. Lo! Eggs! In January? From the old biddies!

Other sonnets:

Here’s where the draft stands.

Routine miracle

I I am, half-willing, a clod of shape: my light stumbles on dark soil, my hush of breath and dread of latchsqueak—but for no reason. At least, no reasoned reason. Just let hens sleep longer than I could this morning. Then wander back pre-dawn to inside routine: Dog food. Coffee. News. The morning, later. Lately dark dawn undulls a bit, revealing a thirsty Oliver awakens in the dim to greet with cacklesong. Her burbling melody rises a chickened good morning. Silent, I nod, navigate hen foxholes as new dawn alights. Daily repeats repeat spring light’s scripts of water, feed, feathers, and now eggs. II Daily repeats repeat spring light’s scripts of water, feed, feathers, and more eggs. I check for them midday, wagering as I walk which corner or nest will hold the clutch, hen warmed and, if she’s there, also crabby liberal with her beak. She’d jam it in my wrist. Six eggs—stolen, to judge from cackled outrage. Lovely Olivers. Jeweled Wyandotte. Plain Buffs. Orb-like, unspherically lumped hengrunts tucked into an end nest, the Wyandotte’s warm. No fight, no bloodied beak, some complaints of unequal exchange: their fruit for my dry feed. A practical reality: hens’ exertions crack for food. From such offerings unwrap beauty’s hidden folds. III Such offerings unwrap beauty’s hidden folds— their shape an effortless, rounded, wordless joy. Here, language’s grasp weakens, turns to gesture that points and sweeps, gathering together the ungatherable, herding wisps and mysteries. Victual egg or ritual egg? No, each of each other. Routine transmutes and points to unseen things, which, unfolded, still easily slip and waver. Unseen until believed; by disbelief unseen, as Herodotus said, not of eggs but of the gods. These eggs I hold outline common miracles, glimmering in reverential sight and lit by thanks. Unevident reality effortlessly unfolds in fingers to show in a clod of shape, sometimes, a light?

How it came together

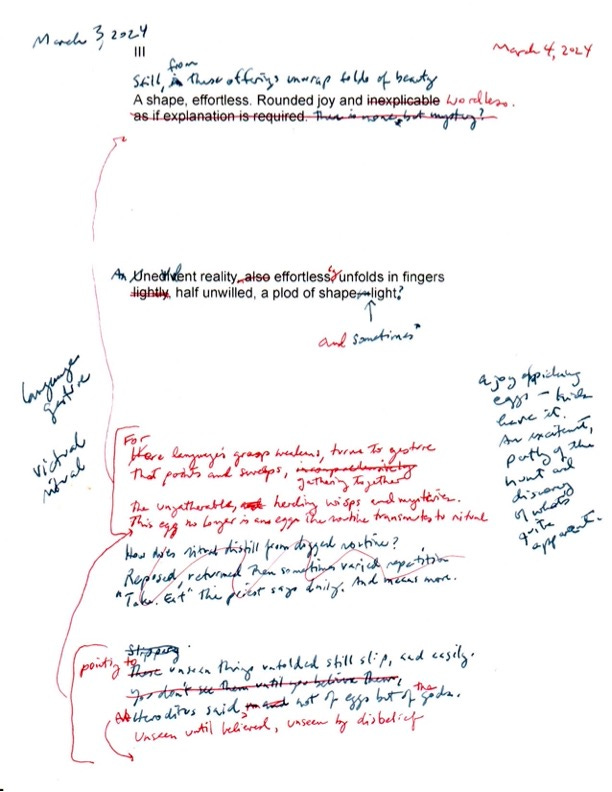

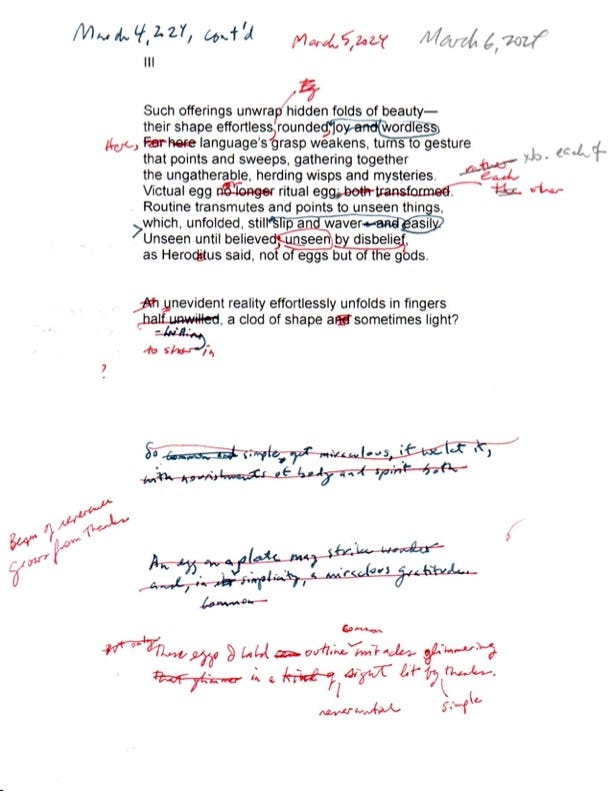

Lines 11-12 of the third sonnet gave me particular trouble. In fact that whole third sonnet was the most difficult to bring together, probably because it departs from the solidity of a material and moves to the unsolid, the immaterial, the world contingent on belief or beauty or reverence. As I wrestled with it (and I still am wrestling, as a matter of fact), I recalled what Wendell Berry said about the inadequacy of language in all of life’s particularity:

In all of the thirty-seven years I have worked here, I have been trying to learn a language particular enough to speak of this place as it is and of my being here as I am.… But when I try to make language more particular, I see that the life of this place is always emerging beyond expectation or prediction or typicality, that it is unique, given to the world minute by minute, only once, never to be repeated. And then is when I see that this life is a miracle, absolutely worth having, absolutely worth saving.

(I quoted a longer passage from Berry’s Life is a Miracle in my last post.) I’ve found that even trying to write poetry bumps me into this problem of particularity and of “miracle.” For the record, I like Berry’s phrase “unevident reality” and I use it in sonnet three, line 13.

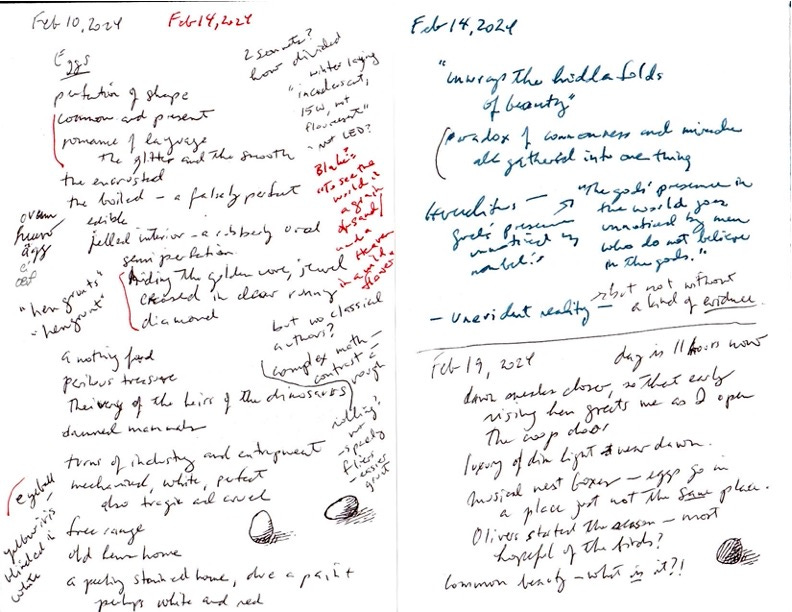

In earlier sonnet posts, I’ve included images of my preparatory notes. Because I have quite a stack of paper this time, I’ll only include a portion of the pages, and the inordinately curious can download the whole batch in the PDF linked below.

I started thinking about the sonnet in late January, and put pen to paper on February 10 — half-sheets to begin with and then, on February 28 I took a full sheet and started “lining things up” into something poetry-like.

Even in the beginning of these notes some inklings of accepted lines appear: “unwrap the hidden folds of beauty” and a quotation from Herodotus, which I think I labeled as from “Heraclitus.” On February 14, I was thinking about an overall theme, and William Blake’s line “To see the world in a grain of sand / and a heaven in a wild flower” came to mind. His “Auguries of Innocence” is worth a read.

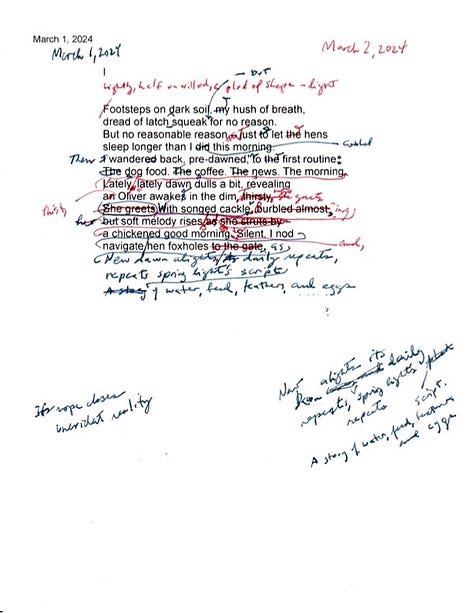

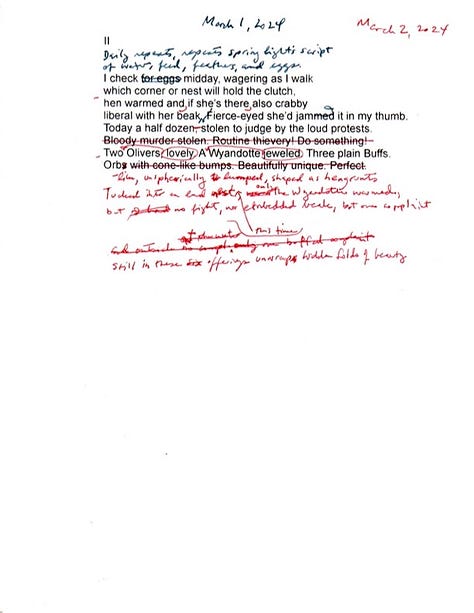

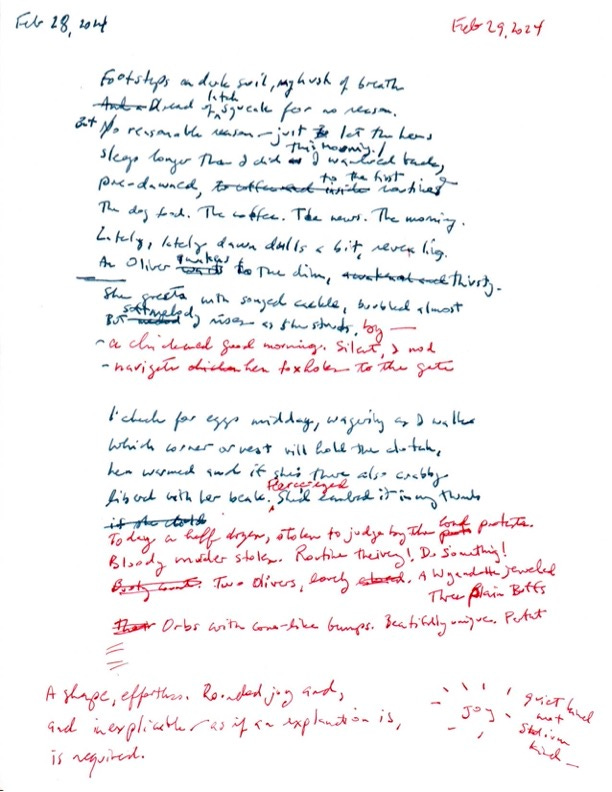

The first attempt tried to grasp two of the sonnets in handwritten form, February 28 and 29 (color-coded ink for each day). The draft is a far cry from the final at this point, and I was befuddled by a third sonnet in the sequence. I knew what I wanted, but I wondered whether I needed three at all. Maybe two? Maybe even one?

On March 1, probably anticipating difficulty, I scrawled, “Words are trout-like things. Slippery beasts and wily. Deceived by flies.” But at the beginning of March, the sequence was coming together:

From the initial concept to the final draft (and it is still a draft), I spent just over a month. In late February and early March I paid the most attention to the sonnets, having laid aside other writing. The lines were somewhat of an obsession, since I’d wake up in the wee morning hours and play with ideas, especially with the last sonnet.

A note on scansion and diction (or at least, use of definite articles)

and I exchange emails occasionally, and I told her about my sonnet project at one point. She responded at one point that writing sonnets “feels like work, forcing experiences into iambs and rhyming schemes.” Actually, I have avoided that kind of iamb-ing and rhyming work, which I, too, think is overwhelming. Keeping some notion of the boundaries of octets and sestets is usually enough for me!But her comment made me wonder what I actually do with the problem of scansion, since I actually have paid quite a bit of attention to the rhythms of reading as I shape the lines. Rhythm is essentially a way of regulating the sound (or internal apprehension) of words, and with that vague notion of rhythmic function I read my lines, evaluate them, and revise them. Do they skip or linger or drum as I want them to?

Sometimes, I’ve been surprised that a rhetorical form will emerge in the revisions. For example: “Unseen until believed; by disbelief unseen, / as Herodotus said, not of eggs but of the gods” (III, ll, 9-10). That includes something of an antimetabole,1 and it does play on different meanings of the word unseen. And the phrase “not of eggs but of the gods” has a whiff of antithesis in it.

Both antimetabole and antithesis are classical rhetorical forms. They still have life in language.

I’m not much for the strict regulation of rhythm for the sake of form. I’ll let others do the awful work of iambic pentameter and the like, but I will play with sound and the aural shapes of language.

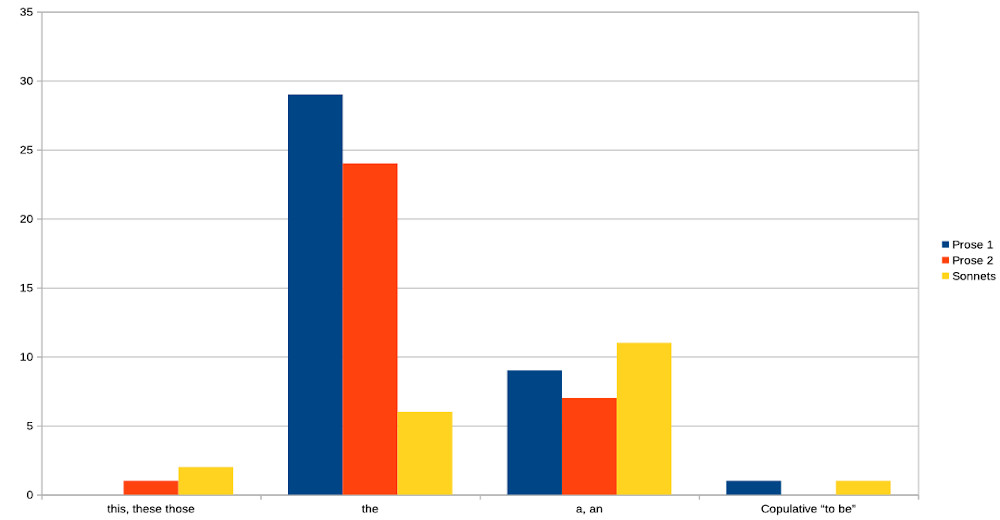

This dive into scansion made me think about the words that got into my sonnets. Specifically, I was wondering, how do words in my prose and my sonnets differ? I did a quick comparison of two randomly selected pieces of prose from a chapter I’ve been revising and a near-done final draft of the sonnets — all identical length at 314 words. I was particularly interested in my use of indefinite and definite articles (a, an, the) and forms of to be (so-called “copulatives” … because I don’t want to be copulating indiscriminately!).

Here’s a graph that shows the numbers:

The main difference among the selected words was in use of definite articles, with more than a five-fold increase in prose over the use in the sonnets. I was surprised by that, but I was also surprised that use of forms of to be in my prose was comparable to the sonnets. I watched my use of to be in the sonnets, but apparently the process of my prose revision takes them out as well.

Got a comment?

Tags: sonnet, egg, chicken, routine, ritual, particular, language, revision, poetry

Links, cited and not, some just interesting

When you don’t have your laptop, good things can happen with pen and paper! Wells, Pete. “Writers: Always Pack a Notebook.” The New York Times, February 28, 2024, sec. Times Insider. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/28/insider/writers-always-pack-a-notebook.html.

The scientists show up to explain. Leonard, Daniel. “A New Equation Can Describe Every Egg.” Scienceline, November 15, 2021. https://scienceline.org/2021/11/a-new-equation-can-describe-every-egg/ and Crespi, Sarah, and Jia You. “Cracking the Mystery of Egg Shape.” Science, June 22, 2017. https://vis.sciencemag.org/eggs/.

Remember this commercial from the 1970s? “Incredible Edible Egg” Commercial (1978). YouTube video, 1978.

A very old and likely very stinky egg. Burchell, Helen. “Aylesbury Roman Egg with Contents a ‘World First’, Say Scientists.” BBC News, February 11, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-beds-bucks-herts-68247184.

She forgot Salvador’s thing with eggs, which he used a lot! (See next item, too.) Nguyen, Celine. “The Humble Egg in Art, Literature, Design, and Theory.” Substack newsletter. Personal Canon (blog), January 9, 2024.

Salvador Dalí really liked eggs. Atlas Obscura. “Dalí Theatre and Museum.” Accessed March 7, 2024. http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/dali-theatre-and-museum.

Byron’s line from Don Juan is the classic example: “Pleasure's a sin, and sometimes sin's a pleasure.”

That first line is MONSTROUSLY good.

"Fowl words is but fowl wind..."